Open Access

Published: November 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.2

Word count: 2,107

About the reviewer

Exhibition review

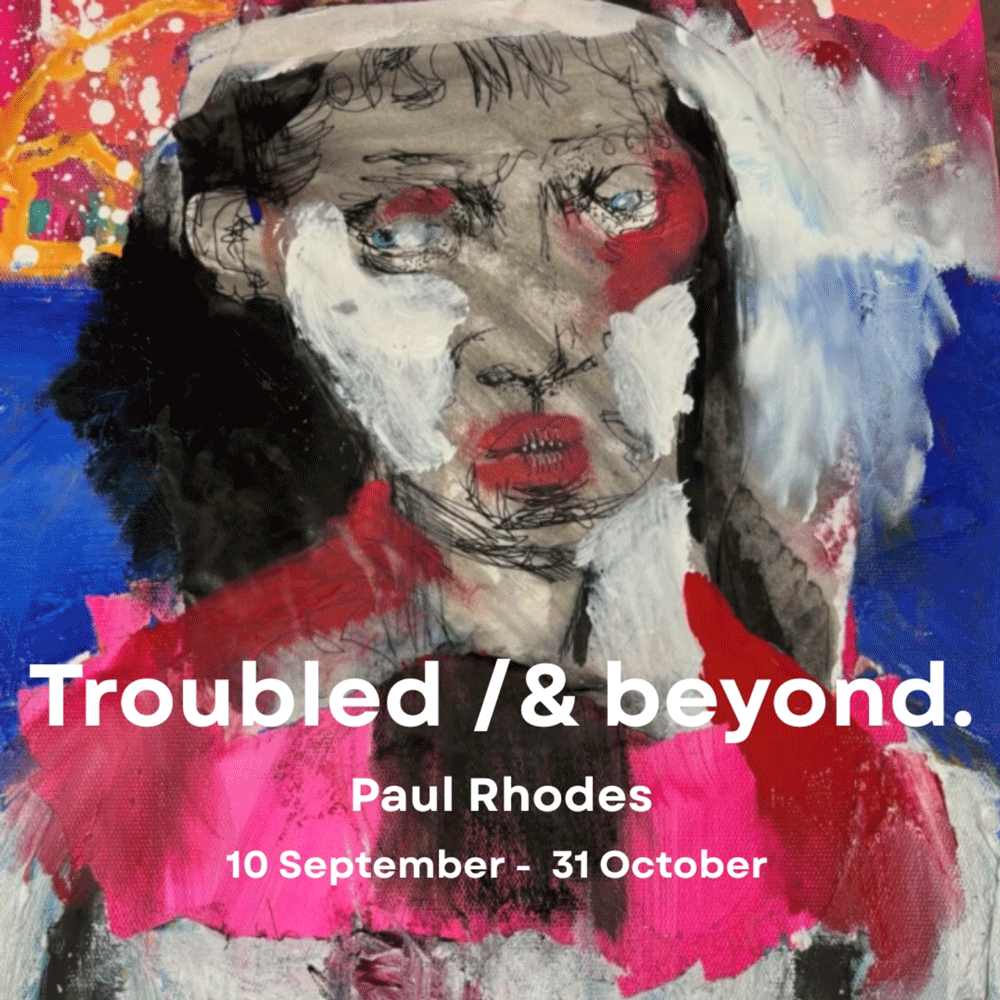

Troubled &/ Beyond, by Paul Rhodes

Held at the Dax Centre, Melbourne

10 September to 31 October 2025

Reviewed by Jasmine Kaur Ahluwalia

My reflections here are sculpted by my own understanding as a creative arts therapist; they are not intended as conclusive readings, but rather as one viewer’s embodied and relational encounter with the art. This review focuses on Troubled &/ Beyond, the recent exhibition by Paul Rhodes held at The Dax Centre from 10 September to 31 October 2025. As a creative arts therapist based in Naarm Melbourne, I have long regarded The Dax Centre as a space of belonging, a place that uniquely bridges art, culture, mental health, and lived experience. Founded on the legacy of Dr Eric Cunningham Dax, a pioneer who advocated for the therapeutic value of art-making and its communal sharing, the Centre now holds an astounding collection of over 15,000 artworks created by individuals with lived experiences of mental ill-health and psychological trauma since 1946 (Koh, 2014).

Context and theoretical lens

Rhodes’ 16-piece series continues this lineage, embodying the ethos of The Dax Centre by artistically exploring emotional and existential struggles within and beyond the therapy space rather than depicting the literal symptoms of mental illness (Koh, 2014). His work traverses the polarities of hope and despair, isolation and belonging, and the anxieties surrounding mental health in contemporary life. With over three decades of experience as a clinical psychologist specialising in individual and family therapy, Rhodes clearly reflects his therapeutic orientation in this exhibition – one that emphasises empowerment over pathology. Through paints, gestures, and abstractions, he has authentically externalised the intricacies of the inner world.

Beyond his clinical and artistic practice, Rhodes is also a Professor of Clinical Psychology at The University of Sydney, widely acclaimed for his scholarship on decolonising psychology, ecological approaches to therapy, and the intersections of post-structural and feminist lenses in clinical work (The University of Sydney, n.d.). His broader body of writing often explores how human suffering is embedded within socio-cultural and environmental systems (Rhodes, 2018). While Troubled &/ Beyond does not overtly foreground these theoretical concerns, their influence can be sensed in the exhibition’s ecological sensibility – the way each piece acknowledges interdependence, reciprocity, and the blurred boundaries between therapist, client, and world.

Positioned within this context, Troubled &/ Beyond can also be read through a creative arts therapy framework – one that acknowledges the shared, relational, and embodied nature of therapeutic witnessing. The art collection foregrounds the therapist’s dual role as both an observer and a participant in the emotional ecology of healing. This resonates with the principle of intersubjectivity in therapy, where meaning emerges in the shared space between therapist and client (Stern, 2004). Rhodes’ art seems to visualise this intersubjective field, revealing how the therapist’s internal landscape is inevitably influenced by the client’s narratives and vice versa. Such self-reflexive artistic inquiry aligns with contemporary creative arts therapy approaches that view art-making as a process of mutual transformation rather than a unilateral intervention (Levine, 2015).

Cite this reviewAhluwalia, J.K. (2025). Exhibition review – Troubled &/ Beyond, by Paul Rhodes. JoCAT, 20(2). https://www.jocat-online.org/r-25-ahluwalia

Embodied witnessing and relational boundaries

Installed across three softly lit walls, the series includes portraits of the therapist’s own embodied reflection within the therapeutic journey and visual dialogues on clients’ experiences of hope, darkness, relationality, and recovery. The whole space subtly echoes the theme of blurred boundaries between therapist and client – how the emotional ecology surrounding each person (therapist and client alike) inescapably converges, and how the role of witness is both challenging and generative. This evokes the phrase ‘one foot in, one foot out’ – a reflection of the therapist’s position (Hadley, 2013), standing between the privilege of service provision and the emotional gravity of clients’ worlds, which undeniably intersect with one’s own identities and humanity (Wood & McKoy-Lewens, 2023). It is within this delicate overlap, where boundaries blur and stories intersect, that the art begins to speak beyond the personal, inviting broader contemplation. From an art therapy lens, the exhibition’s imagery and narratives appear to open a dialogue between the personal and the collective – themes of containment, transformation, and relationality that resonate strongly with therapeutic practice. In creative arts therapy, artworks are inherently open to multiple interpretations. In keeping with this perspective, each image in the exhibition was approached there as an invitation rather than a statement.

Symbolism, colour, and materiality

What stands out most in Troubled &/ Beyond is how Rhodes has used mixed media to explore the dual identity of witnessing and participating in processes of healing, holding the tension between privilege and proximity. The exhibition reimagines therapy as a democratic and reciprocal act. As Potash (2020) reminds us, psychotherapy’s lasting power lies in its democratic values in the reciprocity that strengthens communities, mobilises reform, and humanises both client and clinician. Rhodes’ work portrays a similar impulse: to educate, de-stigmatise, and open the therapy room to public dialogue.

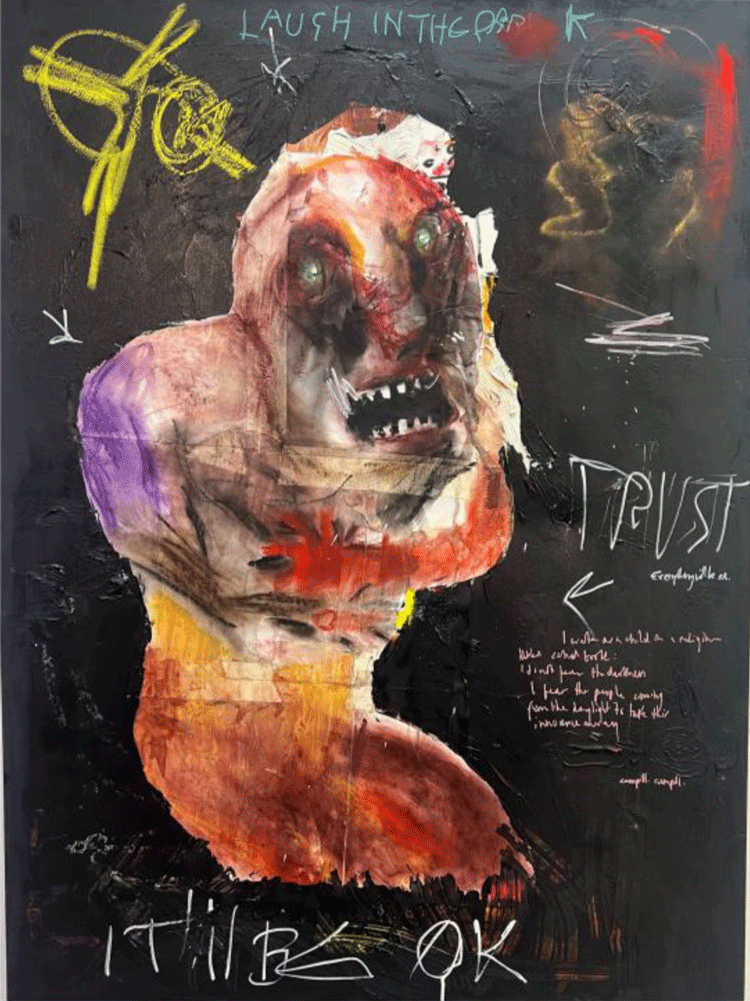

Each artwork is supplemented with a title and short statement that gently sets the tone for the viewers. Love and community emerge as enduring messages – motifs of embrace and shared joy that invite reflection on our collective capacity to heal through connection. The first painting, a self-portrait, perhaps invites reflection on the therapist’s awareness of self within the shared space – resonating with Stern’s (2004) notion of the intersubjective field, a living encounter where both therapist and client shape and are shaped by each other’s presence. Phrases such as “We care a lot?” and “I like uncertainty (not)” evoke the raw humanness of the practitioner. Additionally, Rhodes mentions in his Self-portrait as a Therapist (2025) that “the line between therapist and client is paper thin,” echoing the psychodynamic view that therapists must recognise their own narratives to create genuine space for others (Jung, 1969; Levine, 1997). His paintings also highlight the shared laughter and moments of lightness that emerge in therapy. They are small yet profound reminders that worth is inherent, that even when we fall we remain deserving of love. Rhodes seems to hold both anxiety and hope with equal considerations; it is almost ironic that, amidst the gravity, pieces titled Happy Place and Laugh in the Dark exist, suggesting that joy and unease can coexist.

The Declaration appears to explore the assertion of selfhood through the statement “I am” on the canvas. It echoes the paradox within diagnostic discourse: while on one hand medical models of recovery can feel reductive, the acknowledgment of a diagnosis on the other hand can offer containment or coherence of identity (Lefevre, 2018). The nuance between stigma and self-recognition feels deeply relevant in contemporary conversations about mental health. Rhodes also portrays the therapist’s ongoing dilemmas. For instance, when to ‘push’ for insight and when to allow space for grief and silence. Such tension resonates with the therapeutic dance between holding and accompanying; the capacity to sit beside pain rather than rushing toward cure (Stern, 2010; Winnicott, 1971). In paintings where the therapist’s head expands to fill the canvas, it portrays a vivid image of empathic overload – the anxiety of witnessing pain within a complex social world. From an ecological perspective, Rhodes acknowledges that healing doesn’t occur in isolation, but within embedded systems of culture and community (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Kapitan, 2018). This awareness widens the exhibition’s impact, positioning healing as a collective and ecological process.

Aesthetic process and somatic symbolism

Following the thematic explorations of relationality and containment, Rhodes’ use of mixed media intensifies the process of emotional witnessing. Across the exhibition, the artist paints recurring body figurines and faces, often abstracted or partially obscured, highlighting emotional states rather than depicting any literal identities. On several canvases where helplessness or sorrow are suggested, the gesture of covering the face with palms or fingers becomes a dominant visual metaphor. Such somatic portrayal aligns with art therapy perspectives, where the body is seen as a primary source of expression and psychological truths are shared nonverbally (Kossak, 2015). Rhodes’ deliberate use of colour associations seems to communicate emotional hues. The motifs of community and connection are brushed with yellows and bright oranges, hope and joy are often rendered through cooler blue tones, while anxiety and trauma are smudged with browns and blacks. These choices seem intentional yet intuitive, embodying what McNiff (2004) describes as ‘aesthetic moment’, where meaning-making is done through engagement with colours and textures, rather than through conscious interpretation.

Rhodes’ brushstrokes, while appearing spontaneous, carry a rhythm that feels both free yet intentional, mirroring the paradox of containment and release that often defines creative therapeutic processes. The inclusion of written phrases and fragmented words – some of which are legible while others obscured by layers of paint or shadow – invites viewers into a conversation with the unsaid and the half-formed, reflecting the complexities of communication in therapy. Notably, a recurrent bird metaphor threads across most paintings – from a subtle presence in the first canvas to a more elaborate depiction in the final piece. While its precise symbolism remains open to interpretation, I witnessed it as representing the client’s present state of being. As McNiff (2018) reminds us, the value of art lies not in deciphering its fixed meaning but in allowing what it unfolds in real time. In that moment, the bird seemed to carry the weight of both fragility and flight – perhaps the most suitable metaphor for the therapeutic journey itself.

Reflexive engagement and interpretation

This embodied sense of emergence and layered depth carried over as I engaged with the exhibition more personally. Through the intersecting themes painted across, an image arose within me – two intersecting circles, symbolising the worlds of the therapist and the client. Each carries its own narratives, histories, and silences, yet there is an intersubjective shared space where encounters unfold and transformation becomes a possibility. Around these, I envisioned two larger intersecting circles, representing the broader society – its traumas, conflicts, and collective hopes. This image stayed with me throughout the exhibition, resonating with the way Rhodes’ work seems to hold both the personal and the political, within the same visual context.

What lingered in my mind was how art itself became a reflective container and a medium through which the therapist processed the complexities of what is held within the therapy room. I found myself wondering whether the clients whose narratives inspired these works also had the same access to creative rumination, and how embodied art-making can serve as a democratic bridge for both therapist and client to cohabit with shared vulnerabilities. As Levine (2015) reminds us, the arts offer a contemplative space, not for resolution but for allowing the unspoken to find a symbolic life. Rhodes’ series reminded me of the quiet labour of therapists and how the reflective work extends far beyond the session, breathing in our bodies and conscious presence. The uneven ordering of the paintings, the repetition of motifs, and the emotional flux between canvases all felt genuine to the non-linearity of healing.

Conclusion

Viewing Troubled &/ Beyond in person offered an experience that no digital reproduction could replicate. The physicality of Rhodes’ mixed-media work spoke volumes with its rugged layered textures and the almost tactile traces of urgency and calm. It invited an embodied encounter with the art itself. Standing before each canvas, I could imagine the inner work laboured into by the therapist. The art gave permission to blend the anxiety in the hurried strokes with the companionship in the softer marks and smears. Such an encounter underscores the depth of aesthetic attunement, where our sensory and emotional engagement with art opens a field of resonance that exists beyond just words (Kossak, 2015). The gallery space at The Dax Centre, open and warmly lit, further amplified this sense of connection. It allowed room for envisioning mental health complexities with creativity. Spending time amidst these creations felt like a quiet act of solidarity with artists, clients, and therapists alike. The exhibition’s loud yet compassionate message was unmistakable: to give voice and visibility to the intricacies of lived experiences in mental health, to honour rawness, and to remind us that art continues to be one of the most organic ways of saying we are not alone.

In being present with Rhodes’ imagery, I was reminded that art itself can hold and contain what words often cannot – the silent negotiations between helplessness and resilience, distance and intimacy. The exhibition, much like the therapy space, invited me to sit with the ambivalence rather than resolve it. It extended a visual language for empathy – one that honours both the artist’s vulnerability and the viewer’s sense of responsibility to acknowledge, to feel, to reflect, and to remember. Leaving The Dax Centre, I carried with me not answers, but an honest appreciation for how creative arts continue to bridge the personal and the collective, the troubled and the beyond.

The Dax Centre is a leader in the use of art to raise awareness and reduce stigma towards mental illness through art.

It is located at 30 Royal Parade, in the Kenneth Myer Building, University of Melbourne.

References

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Hadley, S. (2013). Dominant narratives: Complicity and the need for vigilance in the creative arts therapies. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(4), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2013.05.007

Jung, C.G. (1969). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. Princeton University Press.

Kalmanowitz, D.L., Chan, S.M., & Potash, J.S. (Eds.). (2012). Art therapy in Asia: To the bone or wrapped in silk. Jessica Kingsley.

Kapitan, L. (2018). Social action in art therapy. Routledge.

Koh, E. (2014). The Cunningham Dax Collection: A unique mental health resource. Australasian Psychiatry, 22(1), 41–43. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1039856213517951

Kossak, M. (2015). Attunement in expressive arts therapy: Toward an understanding of embodied empathy. Charles C Thomas.

Lefevre, M. (2018). Art as a healing process: Exploring identity, self and transformation in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 23(2), 62–71.

Levine, E.G. (2015). Play and art in child psychotherapy: An expressive arts therapy approach. Jessica Kingsley.

Levine, S.K. (1997). Poiesis: The language of psychology and the speech of the soul. Jessica Kingsley.

McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Shambhala.

McNiff, S. (2018). Imagination in action: Secrets for unleashing creative expression. Shambhala.

Rhodes, P. (2018). Deep ecology and psychotherapy: Re-visioning mental health and illness in the era of the Anthropocene. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 20(3), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2018.1490799

Rhodes, P. (2025). Troubled &/ Beyond [Exhibition]. The Dax Centre, Naarm Melbourne, Australia.

Rhodes, P. (n.d.). Prof Paul Rhodes, Psychologist. St Vincent’s Private Hospital. https://www.svph.org.au/specialists/prof-paul-rhodes-psychologist

Stern, D.N. (2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Stern, D.N. (2010). Forms of vitality: Exploring dynamic experience in psychology, the arts, psychotherapy, and development. Oxford University Press.

The University of Sydney. (n.d.). Professor Paul Rhodes. https://www.sydney.edu.au/science/about/our-people/academic-staff/p-rhodes.html#collapseprofilethemes

Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Playing and reality. Tavistock.

Wood, C., & Mckoy-Lewens, J. (2023). An art therapy education response: Linking inequality and intersectional identity. International Journal of Art Therapy, 28(1–2), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2023.2175000

About the reviewer

Jasmine Kaur Ahluwalia

MA(CAT), AThR, PACFA Reg. Certified Practising

Jasmine Ahluwalia is a Creative Arts Therapist (specialisation in Dance Therapy) based in Melbourne, Australia. She holds a Master of Creative Arts Therapy from the University of Melbourne. With a background in psychology and community-based arts practice, her work explores embodiment, relationality, and the intersections of culture, identity, and healing through the arts. Jasmine’s practice emphasises inclusivity, feminist and relational frameworks, and the power of creative processes to foster well-being and social connection. She is a registered member of the Australian, New Zealand and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association (ANZACATA) and PACFA Certified Practising professional.