Open Access

Published: December 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.2

Word count: 3,920

About the authors

Exploring stress through storytelling in short-form videos created by Thai undergraduate students in Bangkok: A pilot study

Ziyuan Lin and Nisara Jaroenkajornkij

Abstract

This pilot study examines stress, coping mechanisms, and the use of short-form video storytelling among Thai undergraduate students. Fifteen participants created videos, and completed an online form of structured interview questions and surveys. A multimodal qualitative dataset consisting of short-form videos and written reflections was analysed using reflexive thematic analysis to explore emotional expression, coping strategies, and students’ experiences of the creative process. Thematic analysis revealed stress from academics, relationships, and identity, with coping strategies including problem solving, emotional regulation, and social support. Video creation enabled emotional expression and reflection, though challenges such as time limits and vulnerability arose. The findings highlight the therapeutic value of short-form videos as an accessible and culturally relevant tool for supporting youth mental health, offering insights for educators, therapists, and mental health practitioners in Thailand.

Keywords

Undergraduate students, stress, coping mechanism, short-form video, expressive arts therapy

Cite this practice paperLin, Z., & Jaroenkajornkij, N. (2025). Exploring stress through storytelling in short-form videos created by Thai undergraduate students in Bangkok: A pilot study. JoCAT, 20(2). https://www.jocat-online.org/pp-25-lin

Introduction

Emerging adulthood (ages 18–24) is a developmental period marked by identity exploration, emotional fluctuation, and heightened vulnerability to stress (Arnett, 2000). For Thai undergraduate students, academic pressure, social expectations, and uncertainty about the future frequently contribute to chronic stress, which is associated with anxiety, low self-esteem, and harmful coping patterns (Connor et al., 2021; Crum et al., 2020). At the same time, stigma, limited mental health resources, and the absence of structured preventive programmes restrict access to support among Thai youth (Pramukti et al., 2020; Srisopa et al., 2023).

Within this context, creative and expressive approaches, particularly those involving imagery, symbolism, and narrative, offer developmentally appropriate pathways for emotional expression and meaning-making. Expressive Arts Therapy integrates visual, narrative, and symbolic modalities to help individuals externalise inner experiences, regulate emotion, and reauthor personal narratives (Hogan, 2020; Malchiodi, 2022). Storytelling, whether verbal or visual, supports reflection and fosters psychological integration by transforming lived experience into symbolic form (Weiser, 2018; White & Epston, 1990).

Short-form video creation represents a contemporary extension of these expressive processes. Popular platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and CapCut allow young people to combine images, text, sound, and sequencing, mirroring established practices in digital storytelling and therapeutic media work (Cohen & Johnson, 2015; Lambert et al., 2023). Although excessive short-form video consumption can heighten social comparison and anxiety (Arouch et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2019), intentional and guided video creation has been shown to enhance emotional awareness, self-expression, and connection (Turtle et al., 2025; Wang, 2024).

In Thailand, a growing body of work has explored digital storytelling with youth, yet few studies have examined how short-form video can function as an expressive arts medium for understanding stress and coping (Mardhatilah et al., 2023; Puaponpong et al., 2023). Building on both Expressive Arts Therapy literature and digital media research, this pilot study investigates how Thai undergraduate students experience and manage stress through the process of creating short-form video stories.

The study explores three core questions:

What are the key sources of stress among Thai undergraduate students?

What coping mechanisms do students describe?

How do students experience the creative process of short-form video storytelling as a form of emotional expression or reflection?

By examining multimodal data, and students’ short-form videos and written reflections, the study contributes insights into how digital storytelling may serve as an accessible, culturally relevant tool within Expressive Arts Therapy and youth mental health support in Thailand. The videos were only viewed by the researchers and thus the inquiry excludes the experience of these works being viewed by anyone outside of the study.

Background and related work

Stress and coping mechanisms in Thai undergraduate students

Thai undergraduate students commonly experience stress related to academic pressure, social expectations, and concerns about identity and future direction. Previous studies highlight the impact of heavy coursework, competitive environments, and familial expectations on student well-being (Buacharoen et al., 2018; Mekrungrongwong et al., 2023). Limited access to mental health support, shaped by stigma and resource shortages, further compounds these challenges (Unicef Thailand, 2021).

Coping strategies among Thai youth typically include both problem-focused and emotion-focused approaches (Compas et al., 2017). While effective coping can promote resilience and academic adjustment, maladaptive strategies are associated with elevated stress, anxiety, and poor mental health outcomes (Saengthamchai et al., 2023). Understanding how students navigate stress within Thailand’s collectivist cultural context is essential for developing relevant interventions.

Storytelling in Expressive Arts Therapy

Expressive Arts Therapy integrates visual, narrative, and symbolic modalities to support emotional expression, meaning-making, and psychological integration (ANZACATA, 2022; Malchiodi, 2022). Storytelling, whether verbal, visual, or digital, plays a central role in helping individuals externalise experiences and reframe distress within coherent narratives (White & Epston, 1990). Symbolic images, metaphors, and character-based stories provide safe distance and creative flexibility, enabling clients to explore emotions indirectly yet deeply (Hogan, 2020; Loewenthal, 2013).

Photography and other visual media have long been recognised for their therapeutic potential. Phototherapeutic methods help integrate difficult emotions, support identity exploration, and promote reflective dialogue (Weiser, 2018). Videography and digital storytelling expand these possibilities by combining imagery, sound, text, and sequencing, engaging multiple sensory and symbolic layers simultaneously (Lambert et al., 2023). These foundations position storytelling-based digital media as a meaningful, developmentally appropriate modality for university-aged participants.

Short-form video storytelling as a creative modality

Short-form videos, commonly created through mobile applications such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, or CapCut, allow young people to construct brief visual narratives using accessible tools. Research suggests that while excessive consumption of short-form videos can increase distraction, comparison, and anxiety (Arouch et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2019), intentional, guided video creation can enhance emotional awareness, expression, and social connection (Cohen & Johnson, 2015; Turtle et al., 2025; Wang, 2024).

In Thailand, short-form video use is widespread among adolescents and young adults. Emerging studies have begun examining how Thai students use digital storytelling to express stress and identity (Mardhatilah et al., 2023; Puaponpong et al., 2023), yet few have explored its application within an expressive arts framework.

This study builds on these developments by investigating how Thai undergraduate students use short-form video storytelling to articulate stress, express coping strategies, and engage in reflective meaning-making.

Method

Research design

This study used a qualitative design to explore how Thai undergraduate students experience and cope with stress through the creation of short-form video stories. The research focused on three areas: (a) key sources of stress, (b) coping mechanisms, and (c) students’ experiences of the creative process as a form of emotional expression and reflection. A multimodal dataset, including short-form videos and written reflections, was analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2017). This approach was chosen for its suitability in examining lived experience, symbolic meaning, and creative expression within an expressive arts framework.

Participants

Twenty Thai undergraduate students were recruited through voluntary participation, consistent with sample sizes used in exploratory qualitative research on student stress (Aherne, 2012; Trower et al., 2024). Inclusion criteria required participants to: (a) be between 18 and 24 years old, (b) be enrolled in a university in Bangkok, (c) read and write Thai, and (d) have prior experience using short-form video editing applications (e.g., CapCut, TikTok, Instagram).

All participants received a brief guideline on video creation to ensure a consistent creative process. Of the 20 students who enrolled, 15 completed all components – video creation, reflection form, and post-activity survey – and their data formed the final dataset. The study did not seek statistical generalisability; instead, it aimed for thematic richness and depth typical of arts-based and qualitative inquiry.

Procedure

The study was conducted online through a guided expressive arts activity grounded in narrative and symbolic processes. Participants were introduced to a simplified version of The Hero’s Journey, originated from The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Campbell, 1949) as an optional creative scaffold to help structure their video stories. This framework was chosen for its accessibility, cultural resonance, and relevance to therapeutic storytelling in Expressive Arts Therapy.

Participants created a 1–2-minute short-form video depicting their experiences of stress and coping. They were allowed to use any preferred mobile platform and could incorporate imagery, text, music, animation, or license-free media. To protect privacy, participants were instructed not to reveal identifying information and to upload their completed videos privately via Google Drive.

After submitting their video, participants completed a structured online reflection form with open-ended questions about stress, coping, symbolic choices, creative decisions, and their experience of the process. All materials, instructions, and data-collection interfaces were provided in Thai for cultural and linguistic accuracy. Optional one-on-one support was available for participants facing technical or conceptual challenges.

Data analysis

Three data sources – short-form videos, written reflections, and post-activity survey responses – were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2017). Data were analysed in Thai by a native-speaking researcher to preserve nuance, symbolic meaning, and culturally specific expressions. Analysis followed an iterative process:

Familiarisation with videos and written narratives

Initial coding of visual, auditory, and textual elements

Theme development across multimodal data

Refinement of theme structure

Integration of symbolic, narrative, and emotional content

Visual and narrative elements were treated as complementary forms of expression, consistent with multimodal and arts-based research approaches (Barrett et al., 2022; Hacmun et al., 2021). Trustworthiness was supported through systematic documentation, reflexive note-keeping, and adherence to qualitative research standards for transparency and interpretive rigour.

Results

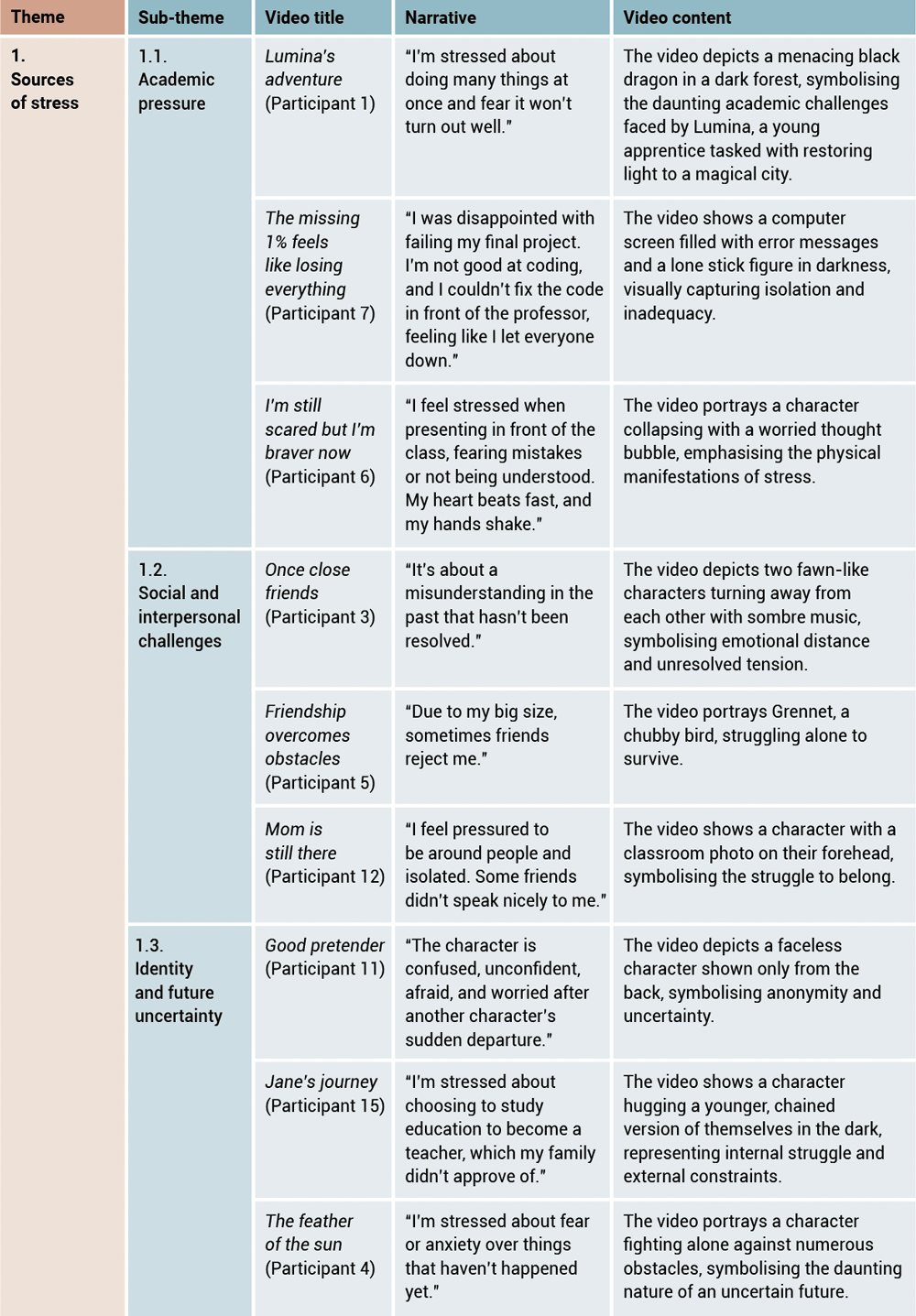

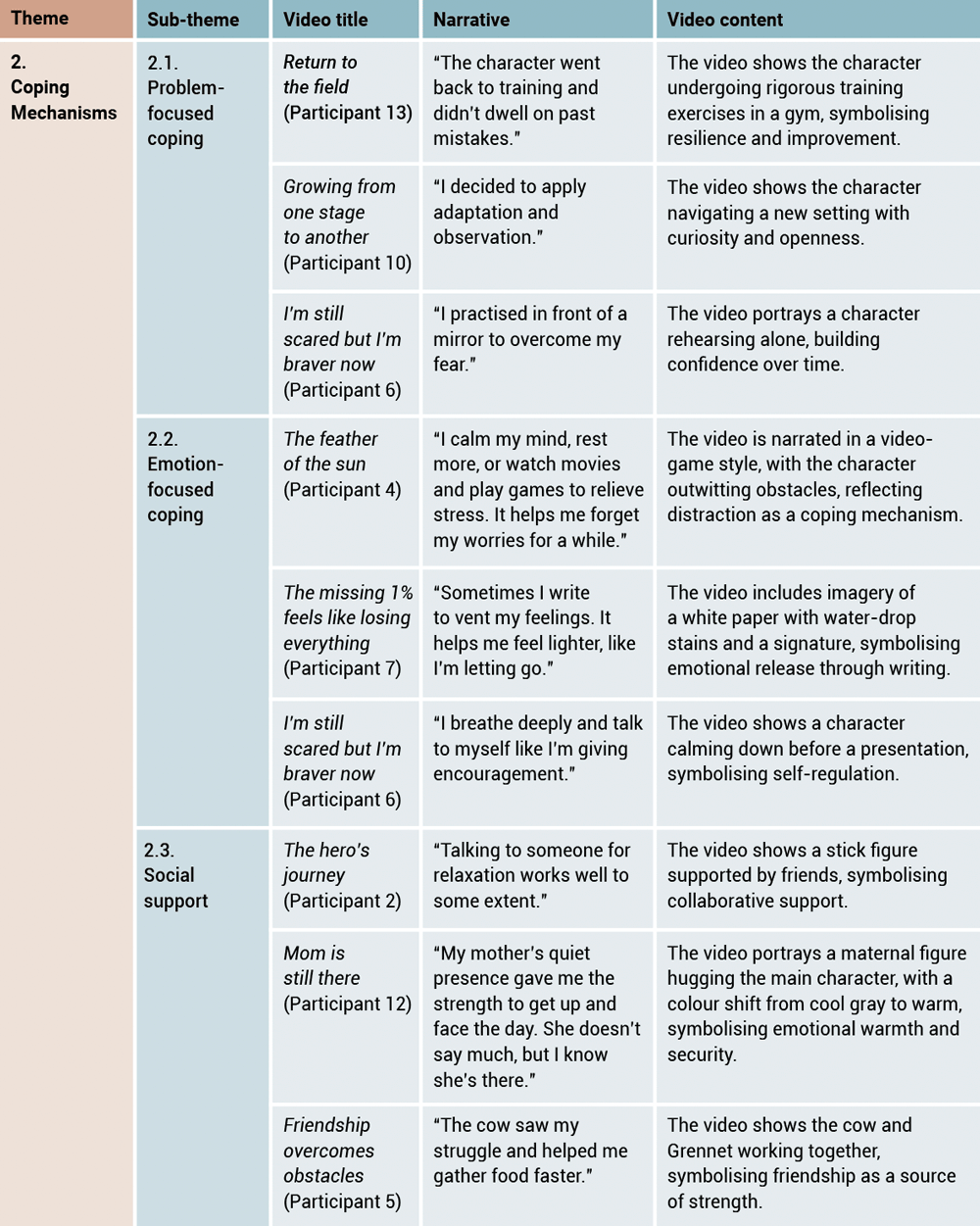

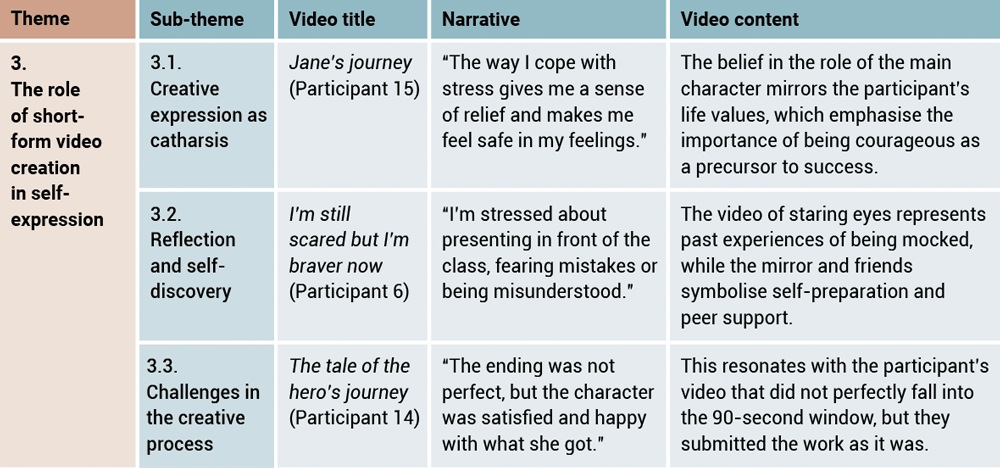

Fifteen participants’ short-form videos and written reflections were analysed to explore how Thai undergraduate students experience stress, employ coping strategies, and engage with the creative process of video storytelling. Three overarching themes were explored: (1) sources of stress, (2) coping mechanisms, and (3) the role of short-form video creation in self-expression. Each theme contained three sub-themes that reflected the emotional, relational, and symbolic nuances present across the dataset (Tables 1–3).

Table 1. Themes, sub-themes, video title, narrative, and video content – Sources of stress.

Table 2. Themes, sub-themes, video title, narrative, and video content – Coping Mechanisms.

Table 3. Themes, sub-themes, video title, narrative, and video content – The role of short-form video creation in self-expression

Theme 1: Sources of stress

This theme highlights the intersecting stressors Thai undergraduate students face, shaped by academic demands, social relationships, and personal identity development. The three sub-themes – academic pressure, social and interpersonal challenges, identity and future uncertainty – illustrate how these stressors emerge in students’ lived experiences.

Sub-theme 1.1: Academic pressure

Academic demands were the most common stressor, reported by nearly half the participants. Students described coursework overload, tight deadlines, high-stakes assessments, and pressure from peers, instructors, and family. This aligns with prior studies on academic stress in higher education (Barbayannis et al., 2022; Rhein & Nanni, 2022). Participant 1 (Lumina’s adventure) depicted this burden through a dark forest scene where a menacing black dragon represents the fear of failing to manage multiple tasks, with the narrative: “I’m stressed about doing many things at once and fear it won’t turn out well.” This framing externalises stress as a mythic antagonist, revealing how academic pressure can take on monstrous emotional proportions.

Sub-theme 1.2: Social and interpersonal challenges

Participants reported stress from interpersonal issues such as unresolved conflict, social exclusion, and pressure to maintain harmony in groups. These relational stressors mirror findings on the impact of peer relationships on youth mental health (Auerbach et al., 2018), which are heightened in Thailand’s collectivist culture, which values social cohesion and avoiding confrontation (Buacharoen et al., 2018). Participant 12 (Mom is still there) conveyed feelings of social discomfort and alienation: “Being in a new environment – surrounded by people – still leaves me feeling lonelier than ever... This environment made me feel like I didn’t belong.” In the video, a classroom photo placed on the character’s forehead symbolises the tension between the pressure to belong and the invisibility felt within a group. The image reflects how social identity can become an imposed and emotionally burdensome label.

Sub-theme 1.3: Identity and future uncertainty

Participants described stress linked to uncertainty about identity, career paths, and long-term goals. Such concerns are typical in emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000), and are often amplified in cultures where family and societal expectations shape life choices (Srisopa et al., 2023). Participant 11 (Good pretender) portrayed confusion and insecurity: “The character is confused, unconfident, afraid, and worried after another character’s sudden departure.” The faceless figure shown from behind symbolises lost self-definition and internal uncertainty, while the other’s departure suggests a triggering event that deepens this disorientation.

These three sub-themes show that Thai undergraduates experience stress through the intertwined pressures of academic expectations, social dynamics, and identity formation. Participants’ narratives and visuals reveal deeper emotions of inadequacy, isolation, and inner conflict. In Thailand’s collectivist context, the drive to meet external expectations often intensifies these struggles, making stress both a personal and a cultural experience. These findings highlight the need for approaches that address student stress within both individual and cultural dimensions.

Theme 2: Coping mechanisms

This theme explores the strategies Thai undergraduate students use to manage stress, reflecting a balance between personal resilience and relational support. Three sub-themes emerged – problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and social support – aligning with Folkman and Lazarus’ (1980) coping framework. Within Thailand’s collectivist culture, where harmony and family expectations shape emotional responses, these strategies reveal how individual agency and social context jointly support recovery and growth.

Sub-theme 2.1: Problem-focused coping

Participants used proactive strategies to tackle stressors directly, including persistence, skill building, and seeking resources – consistent with Folkman and Moskowitz’s (2004) framework on effective problem-focused coping. Participant 13 (Return to the field) emphasised growth through skill development: “The character went back to training and didn’t dwell on past mistakes.” The video’s gym training scenes visually reinforce themes of resilience and a forward-looking mindset.

This example illustrates how problem-focused coping empowered participants to reframe adversity as an opportunity for action. Rather than merely enduring stress, they viewed it as a challenge to be met with effort, practice, and persistence.

Sub-theme 2.2: Emotion-focused coping

Participants used emotion-focused strategies such as writing, self-reflection, entertainment, physical activity, and mindfulness to manage their stress, especially when stressors felt uncontrollable (Crum et al., 2020). Participant 7 (The missing 1% feels like losing everything) shared, “Sometimes I write to vent my feelings. It helps me feel lighter, like I’m letting go.” The video’s imagery of a white paper marked with water stains and a signature symbolises emotional release through written expression.

This narrative illustrates how emotion-focused strategies function as adaptive tools for managing internal distress. Though not directed at changing the stressor itself, these methods offer crucial emotional relief, often depicted through symbolic moments of release, escape, or transformation. Writing, in particular, serves as both catharsis and a means of reclaiming agency through narrative, while moments of distraction reflect the tension between confrontation and avoidance – a recurring theme in individual coping.

Sub-theme 2.3: Social support

Participants identified social support as a key coping mechanism, relying on friends, family, and trusted individuals to manage stress. This reflects Thailand’s collectivist culture, where interpersonal harmony and emotional interdependence are central to well-being (Buacharoen et al., 2018). Participant 2 (The hero’s journey) highlighted the soothing power of emotional connection: “Talking to someone for relaxation works well to some extent.” In the video, a guiding fairy accompanies the protagonist through danger, symbolising the grounding and supportive presence of trusted relationships during challenging times.

Across the three sub-themes, participants showed diverse coping strategies – problem focus, emotional focus, and social support – reflecting both personal agency and Thailand’s collectivist values. Coping was portrayed as an ongoing process of adaptation and meaning-making, where persistence, emotional release, and relationships transformed stress into growth and self-understanding through short-form storytelling.

Theme 3: The role of short-form video creation in self-expression

This theme examines how creating short-form videos served as a medium for emotional expression, self-reflection, and transformation. Grounded in Expressive Arts Therapy and The hero’s journey framework, participants used storytelling to externalise struggles and find new meaning. The three sub-themes – creative expression as catharsis, reflection and self-discovery, and challenges in the creative process – highlight both the therapeutic potential of digital media and the emotional and technical complexities of creation.

Sub-theme 3.1: Creative expression as catharsis

Participants described video creation as a therapeutic outlet for emotional expression, consistent with Expressive Arts Therapy principles (Malchiodi, 2022). Feedback from the Experience Survey highlighted it as a structured yet creative space for releasing emotions and processing inner turmoil. This aligns with Saladino et al. (2020), who noted that therapeutic filmmaking offers a safe container for difficult emotions through visual storytelling. Participant 15 (Jane’s journey) portrayed a protagonist pursuing a dream despite resistance: “The way I cope with stress gives me a sense of relief and makes me feel safe in my feelings”. The story reflects the participant’s values, linking courage with emotional safety. Through digital storytelling, they could embody and observe their emotions, creating space for reflection and release. Symbolic elements – chains, a younger shadow-self, and shifts from dark to warm tones – transform inner turmoil into visible metaphors. In the final scene, light falls on the character as she embraces her younger self, symbolising healing, self-acceptance, and reclaimed agency. Here, video creation becomes a reparative process, turning coping into an act of resilience and hope.

Sub-theme 3.2: Reflection and self-discovery

Creating and reviewing short-form videos allowed participants to reflect on their stress and coping strategies, deepening self-awareness and emotional insight. Many shared that crafting their narratives helped them reassess challenges, recognise hidden strengths, and view themselves with greater compassion. This aligns with Simons’ (2022) view that storytelling fosters self-understanding by shaping personal experience into meaningful structure. Participant 6 (I’m still scared but I’m braver now) illustrated this through Annie’s journey – in which a child overcomes fear of public speaking through practice and encouragement – blending symbolism and personal growth within the six-piece story-making framework (Lahad, 2013).

Sub-theme 3.3: Challenges in the creative process

While many participants found video creation meaningful and therapeutic, several faced challenges, including time constraints, technical issues, and emotional vulnerability. These difficulties highlight the structural and emotional complexity of self-expression through digital media, echoing Nguyen’s (2023) call for both technical and emotional support in digital storytelling. The 30–90-second limit proved particularly demanding, forcing choices about what to include or omit. Participants also noted frustrations with storage, editing, and exporting. More significantly, some experienced emotional resistance when revisiting painful memories, as transforming lived experience into narrative required confronting unresolved emotions – an experience that was both cathartic and unsettling. Participant 14 (The tale of the hero’s journey) described their video as “a story about a woman who expresses herself through her drawings, and the story in that book reflects her life journey.” At the 90-second mark, the protagonist appears centred against a bright background – a visual turning-point symbolising emergence, visibility, and quiet acceptance. This moment serves as both a narrative and a symbolic resolution.

These sub-themes illustrate how symbolic elements are presented in the video content, along with narrative structures under each theme and sub-theme in the thematic analysis.

Discussion

This study examined how Thai undergraduate students experience stress, cope with challenges, and use short-form video storytelling as a means of emotional expression. It focused on three themes – sources of stress, coping mechanisms, and the role of short-form video creation in self-expression – highlighting how digital storytelling can function as a culturally relevant expressive arts modality for young people.

Sources of stress

Participants’ stressors centred on academic pressures, interpersonal challenges, and uncertainty surrounding identity and future direction. These findings align with research showing that Thai university students commonly experience high academic expectations, competitive environments, and strong familial influence on educational and career decisions (Pramukti et al., 2020; Srisopa et al., 2023). The videos’ symbolic imagery of dragons, dark forests, faceless figures, and constrained younger selves visually captures internal conflicts consistent with Expressive Arts Therapy principles, where metaphor and symbol externalise emotional states (Malchiodi, 2022; Weiser, 2018). The visual metaphors used by participants not only reinforced how stress was experienced cognitively, but embodied and expressed through imaginative forms.

Coping mechanisms

Participants described a mix of problem-focused efforts (e.g., preparation, rehearsal, and persistence), emotion-focused strategies (e.g., journaling, distraction, and self-talk), and reliance on social support from peers and family. These findings mirror established models of coping that distinguish between direct problem-solving and emotion regulation (Compas et al., 2017; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). The prominence of social support reflects Thailand’s collectivist cultural orientation, where emotional connection and family presence are central to managing distress (Buacharoen et al., 2018). Symbolically, characters such as helpers, companions, and maternal figures served as visual anchors of support, reinforcing the importance of relational resources in resilience.

Short-form video creation as self-expression

A key contribution of this study is the insight into how short-form video creation supported emotional expression, reflection, and meaning-making among participants. Many described the creative process as cathartic, enabling them to transform internal experiences into symbolic narratives. This aligns with Expressive Arts Therapy frameworks that emphasise aesthetic distance, symbol formation, and creative play as mechanisms for emotional regulation and insight (Hogan, 2020; Loewenthal, 2013). By working with metaphors, imagery, and structured storytelling, participants externalised difficult emotions in safe, indirect ways – mirroring therapeutic storytelling or digital narrative approaches used in Expressive Arts Therapy (Cohen & Johnson, 2015; Lambert et al., 2023).

Participants also reported experiencing self-discovery through reviewing and constructing their videos. This reflective function is consistent with literature showing that narrative reconstruction and creative media can foster self-awareness, reauthoring of experience, and a sense of agency (Rogers et al., 2023; White & Epston, 1990). The visual motifs of journeys, transitions from darkness to light, and characters gaining confidence highlight how students revisited and reframed their experiences through symbolic sequences.

At the same time, several participants identified challenges in the creative process, including time constraints, technical difficulties, and the emotional weight of revisiting stressful memories. These obstacles reflect broader concerns in digital storytelling research regarding technical barriers and the need for emotional scaffolding when engaging participants in expressive digital work (Nguyen, 2023). The tension between limited format (e.g., 90 seconds) and complex emotional stories suggests that structured support and clear containment may be essential when applying short-form video creation in therapeutic contexts.

Implications for Expressive Arts Therapy and youth mental health

Findings from this pilot study suggest that short-form video storytelling is an accessible, developmentally appropriate tool for exploring emotions, particularly among digitally fluent youth. The modality aligns naturally with Expressive Arts Therapy practice, combining imagery, sound, sequence, metaphor, and narrative in a multimodal format. It may be especially useful in settings where students struggle to articulate feelings verbally or where stigma limits help-seeking. Integrating guided video creation into workshops, support programmes, or therapeutic groups could provide a culturally relevant pathway for emotional expression and peer connection.

Limitations and future research

This pilot study has several limitations. The sample was small, self-selected, and limited to undergraduate students in Bangkok, which restricts transferability to more diverse populations. Data relied on self-reported reflections and short-form videos, creating potential for selective disclosure, and the interpretive nature of thematic analysis introduces subjectivity despite reflexive rigour. The creative process also evoked emotional content for some participants, highlighting the need for clearer containment when using digital storytelling outside therapeutic settings.

Future research should explore more diverse and rural groups, use mixed-methods or longitudinal designs to examine changes over time, and compare short-form video creation with other expressive arts modalities. Investigating how digital storytelling can be safely integrated into therapeutic or educational programmes may further inform its potential as an accessible tool for youth mental health and Expressive Arts Therapy.

Conclusion

This pilot study examined how Thai undergraduate students express stress, cope with challenges, and reflect on their experiences through short-form video storytelling. Participants represented academic pressure, relational difficulties, and identity uncertainty through symbolic imagery, and described using a range of coping strategies supported by personal effort, emotional regulation, and social connection. The creative process itself functioned as an accessible form of emotional expression and reflection, illustrating the potential of short-form videos as a culturally relevant expressive arts modality for digitally fluent youth.

Although exploratory, the findings highlight an emergent avenue for integrating guided digital storytelling into mental health and educational settings. Short-form video creation may offer young people a familiar, low-threshold way to articulate inner experiences, engage with metaphor, and foster self-awareness within supportive environments. With further research, this modality may contribute to the expanding toolkit of Expressive Arts Therapy approaches for youth mental well-being.

Images

These images were generated by the author using ChatGPT. Original participant video stills are not shown due to ethical protocols of the research. These AI-generated images were created based on descriptions of participant artworks with all the components included without displaying their work.

References

Aherne, D. (2012). Understanding student stress: A qualitative approach. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 22(3–4), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.2001.10558278

ANZACATA. (2022, 18 October). About creative arts therapies. The Australian, New Zealand and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association. https://anzacata.org/About-CAT

Arnett, J.J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469.

Arouch, S., Edgcumbe, D., Pezaro, S., & da Silva, K. (2025). The impact of short-form video use on cognitive and mental health outcomes: A systematic review. medRxiv, 2025-08. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.08.27.25334540

Auerbach, R.P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D.D., Green, J.G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M.K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N.A., Stein, D.J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A.M., Kessler, R.C., & WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362

Barbayannis, G., Bandari, M., Zheng, X., Baquerizo, H., Pecor, K.W., & Ming, X. (2022). Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: Correlations, affected groups, and COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 886344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.886344

Barrett, H., Holttum, S., & Wright, T. (2022). Therapist and client experiences of art therapy in relation to psychosis: A thematic analysis. International Journal of Art Therapy, 27(3), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2022.2046620

Buacharoen, P., Techapunratanakul, N., Dornchai, G., & Buochareon, P. (2018). Strain and adaptation of bachelor degree students from faculty of engineering, Rajmangala University of Technology Lanna Chiangmai Campus. Journal of Graduate Studies Review MCU Phrae, 4(2), 37–58.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces (Vol.17). New World Library.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Cohen, J.L., & Johnson, J.L. (2015). Introduction: Film and video as a therapeutic tool. In J.L. Cohen, J.L. Johnson & P. Orr (Eds.), Video and filmmaking as psychotherapy (pp.3–12). Routledge.

Compas, B.E., Jaser, S.S., Bettis, A.H., Watson, K.H., Gruhn, M.A., Dunbar, J.P., Williams, E., & Thigpen, J.C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000110

Connor, D.B., Thayer, J.F., & Vedhara, K. (2021). Stress and health: A review of psychobiological processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

Crum, A.J., Jamieson, J.P., & Akinola, M. (2020). Optimizing stress: An integrated intervention for regulating stress responses. Emotion, 20(1), 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000670

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R.S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219-239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J.T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 745–774. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

Hacmun, I., Regev, D., & Salomon, R. (2021). Artistic creation in virtual reality for art therapy: A qualitative study with expert art therapists. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 72, 101745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101745

Hogan, P. C. (2020). Style in narrative: Aspects of an affective-cognitive stylistics. Oxford University Press.

Lahad, M. (2013). Six-piece story-making revisited: The seven levels of assessment drawn from the 6PSM. In M. Lahad, M. Shacham & O. Ayalon (Eds.), The “BASIC PH” model of coping and resiliency: Theory, research and cross-cultural application (pp.47–60). Jessica Kingsley.

Lambert, C., Egan, R., Turner, S., Milton, M., Khalu, M., Lobo, R., & Douglas, J. (2023). The digital bytes project: Digital storytelling as a tool for challenging stigma and making connections in a forensic mental health setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136268

Loewenthal, D. (2013). Talking pictures therapy as brief therapy in a school setting. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 8(1), 21-34.

Malchiodi, C.A. (2022). Handbook of expressive arts therapy. Guilford.

Mardhatilah, D., Omar, A., Ramayah, T., & Juniarti, R. (2023). Digital consumer engagement: Examining the impact of audio and visual stimuli exposure in social media. Information Management and Business Review, 15(4), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.22610/imbr.v15i4(SI)I.3580

Mekrungrongwong, S., Mekrungruangwong, T., Intha, P., Keardsompron, P., Khanti, P., Dongsa, P., Pengma, P., & Saikampa, M. (2023). Factors predicting stress among undergraduate students in Naresuan University. Journal of Public Health and Health Sciences Research, 5(2), 151-165. https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JPHNU/article/view/260410

Nguyen, T-H. (2023). Exploring short-form videos addiction: Understanding influential factors from the perspective of the stress-coping theory. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Management and Business (COMB-2023), 451–471. Zenodo.

Pramukti, I., Strong, C., Sitthimongkol, Y., Setiawan, A., Pandin, M.G.R., Yen, C-F., Lin, C-Y., Griffiths, M. D., & Ko, N-Y. (2020). Anxiety and suicidal thoughts during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-country comparative study among Indonesian, Taiwanese, and Thai university students. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(12), e24487. https://doi.org/10.2196/24487

Puaponpong, W., Thongdee, N., & Chutanopmanee, V. (2023). Correlation between the use of short-form video and everyday life attention in Thai high school students. International Journal of Current Science Research and Review, 6(8), 5983–5991. https://doi.org/10.47191/ijcsrr/V6-i8-66

Rhein, D., & Nanni, A. (2022). Assessing mental health among Thai university students: A cross-sectional study. Sage Open, 12(4), 21582440221129248. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221129248

Rogers, B.A., Chicas, H., Kelly, J.M., Kubin, E., Christian, M.S., Kachanoff, F.J., Berger, J., Puryear, C., McAdams, D.P., & Gray, K. (2023). Seeing your life story as a Hero’s journey increases meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(4), 752–778. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000341

Saengthamchai, W., Parnichakul, R., Piyawatcharametha, S., Sornsawad, A., Sookon, C., & Chaiakkaratkan, N. (2023). The effect of stress in learning adjustment on coping of 1st and 2nd year undergraduate level engineering students in a dormitory of a university. Journal of Social Sciences in Measurement Evaluation Statistics and Research, 4(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.14456/jsmesr.2023.4

Saladino, V., Sabatino, A.C., Iannaccone, C., Giovanna Pastorino, G.M., & Verrastro, V. (2020). Filmmaking and video as therapeutic tools: Case studies on autism spectrum disorder. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 71, 101714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101714

Simons, S. (2022). Narrative expressive arts therapy. In C.A. Malchiodi, (Ed.), Handbook of expressive arts therapy (pp.170–185). Guilford.

Srisopa, P., Moungkum, S., & Hengudomsub, P. (2023). Factors predicting depression, anxiety, and stress of undergraduate students in the eastern region of Thailand. Nursing Science Journal of Thailand, 41(3), 109–122. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ns/article/view/260049

Trower, R., Hurley, L., Murphy, E.R., Durand, H., Farrell, K., Meade, O., Molloy, G.J., & McSharry, J. (2024). Understanding the stress and coping experiences of undergraduate university students in the COVID-19 context: A qualitative study. HRB Open Research, 5(51), 51. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13573.1

Turtle, L., Wesson, H.A., Williamson, S., & Hodson, N. (2025). Short-form psychoeducation videos: Process development study. JMIR Formative Research, 9(1), e66884. https://doi.org/10.2196/66884

Unicef Thailand. (2021, October 8). COVID-19 pandemic continues to drive poor mental health among children and young people. https://www.unicef.org/thailand/press-releases/covid-19-pandemic-continues-drive-poor-mental-health-among-children-and-young-people

Wang, W. (2024). Exploring the impact of social media short-form videos on adolescents’ psychological and psychosocial well-being. SHS Web of Conferences, 199, 02016. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202419902016

Weiser, J. (2018). Phototherapy techniques: Exploring the secrets of personal snapshots and family albums. Routledge.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. W.W. Norton.

Zhang, X., Wu, Y., & Liu, S. (2019). Exploring short-form video application addiction: Socio-technical and attachment perspectives. Telematics and Informatics, 42, 101243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101243

Authors

Alin Ziyuan Lin

MA EAT, BA

Alin is an MA in Expressive Arts Therapy graduate based in Bangkok, Thailand, with a multicultural background. She entered therapy through the back door of the motion picture industry. With experience in storytelling, picture, and audio production, she is drawn to how visual, sound, and narrative elements influence emotions. Her curiosity lies in how short videos serve as contemporary platforms for stress relief, self-expression, and communication for today’s generation. Alin believes creativity communicates when words fall short, and a screen is a black mirror that could reflect one’s inner self.

Nisara Jaroenkajornkij

PhD, MSc, BSc, BAAT

Nisara is a lecturer in the MA Expressive Arts Therapy Programme at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, Thailand and a researcher with The FAA-Emili Sagol Creative Arts Research and Innovation for Well-being Center. Her work focuses on expressive arts therapy, mixed-methods and qualitative research, and trauma-informed practices across community and educational settings. She is particularly interested in how creative processes support emotional regulation, resilience, and recovery following individual and collective adversity. Nisara’s current research examines community-based trauma interventions and arts-informed practices that support healing and emotional regulation among abused children.