Open Access

Published: December 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.2

Word count: number

About the authors

Exploring supervision pedagogy through collaborative art-based reflection: Reworking a single expressive surface

Tess Crane, Kate Richards, Pam Hellema, Carmen Millic and Sally Goldstraw

Abstract

This paper presents an art-based inquiry into the practice of educational supervision. Inspired by the one-canvas supervision model, a team of art therapy educators engaged with a process of sequentially layering and reworking diverse materials upon one surface, to explore unique and in-depth understandings of educational supervision pedagogy. We found that the role of diverse materials was highly valued and the one surface offered new insights through themes of reconstruction, transformation and metaphor, underscoring relational and arts-based supervision approaches. Additionally, collectively reflecting upon the one-surface process offered meaningful professional development and invigorated our identities as art therapy educators.

Keywords

Art therapy education, art-based supervision, reflexive practice

Cite this practice paperCrane, T., Richards, K., Hellema, P., Millic, C. & Goldstraw, S. (2025). Exploring supervision pedagogy through collaborative art-based reflection: Reworking a single expressive surface. JoCAT, 20(2). https://www.jocat-online.org/pp-25-crane

Introduction

The process of facilitating supervision in a postgraduate art therapy program is a dynamic experience, whereby the educator relies on their accumulated knowledge as a practicing art therapist, but also their capacity to step into the stance of mentor and teacher (Moon, 2003). This interplay between the clinical and educational role is one that necessitates the maintenance of a reflexive practice to illuminate the boundaries of the role, as shaped by the student’s learning needs, but also to find focus in the supervisory exchange in the classroom.

There is an extensive pool of research that explores the context of art therapy teaching practice and supervision within our training programs, both in Australia and internationally. Some of the complex and enduring issues represented in the literature explore: centralising the art-making process in learning (Cahn, 2000; Deaver, 2012; Deaver & McAuliffe, 2009); the relational dynamics that are essential to support learning needs of art therapist trainees (Crane & Byrne, 2020; Green, 2020; Moon, 2003; Skaife et al., 2016), important context-bound ethical and professional questions in rigorous training (Fenner & Byrne, 2019; Potash et al., 2012; Westwood & Linnell, 2011) and grappling with contemporary questions in online learning environments in a post-Pandemic world (Byrne & Crane, 2021; Toll, 2022).

To build on these established understandings within our professional community, we were drawn to exploring our supervision teaching practice through an art-based process. As a group of art therapy supervision educators, we have been curious about the role of the one-surface process (Miller, 2012, 2020). We have found this process of reflective art-making on the same surface, layered and reworked across supervision sessions, to be supportive of the emerging clinical insights of trainee art therapists. We have also experienced it as a mechanism for supervisors to better understand the active factors of art therapy supervision within the educational context (Lis-Ron et al., 2024, 2025).

The emerging question

This inquiry emerged from a process of coming together as a team of art therapy supervision colleagues. We have a shared professional experience of teaching in the supervisory component of a placement program within a Master of Art Therapy degree. In supporting best practice, we were interested in developing a greater understanding of the model of supervisory practice within our program, to both better prepare students for the group supervision learning experience and orient staff to a model of practice that sits within a cohesive educational frame.

In early meetings, we noted that supervision practice often requires educators to leverage clinical knowledge in ‘responsive’ ways to support student learning needs. Common factors were identified where we agreed on the importance of art-making practice in supervision and the supervisor’s willingness to step into the role of mentor and professional role model. Whilst these foundations were clear, we were interested to see if a collective art-based process would provide further opportunity to map and detail the experience of educational art therapy supervision.

Mapping the process of inquiry and identifying a focus

In situating the context of this inquiry, we were drawn to the ethic of arts-based inquiry (McNiff, 2008, 2018) whereby the “systematic use of the artistic process… as a primary way of understanding and examining experience” (McNiff, 2008, p.29) is centralised. By engaging with the one-surface process we aimed to explore our experiences and understandings of the key dimensions of the supervisory learning context in postgraduate training.

There are points of intersection between our experience as clinicians and how we reflect on teaching scholarship. In this reflexive inquiry we integrated perspectives of openness, curiosity and the not-knowing stance, as an orientation we have learnt from observing our own teachers and one we have then proceeded to implement in clinical practice. To support the inquiry, we brought a commitment to the inherent value of process (Lett et al., 2014), for its capacity to generate understanding and new knowledge. In addition, we were interested in the opportunity to bring what Van Lith and Bulosan (2022) describe as “an exploratory and investigative lens … which [led] us to developing a deeper capacity for understanding….” (p.119) as a way of orienting to this experiential mode of inquiry.

The one-surface process

This inquiry captured the supervision experience at one point in time. We have purposely scaled this inquiry to follow a more responsive and reflexive approach, heavily embedded in art-based ways of evaluating practice (Fish, 2008). This inquiry is fundamentally informed by the art-based one-canvas method (Brown & Wilson, 2023; Lis-Ron et al., 2024, 2025; Miller, 2012, 2019, 2020, 2022, 2023; Miller & Robb, 2017; Robb & Miller, 2017). The traditional material qualities, paint and canvas, were adapted to include the authors’ choice of reworking a three-dimensional ‘surface’, to reflect on the key and complex dimensions of supervisory practice.

Miller (2020) describes the one-canvas process as an “ongoing experience of having continual encounters with change processes on one surface over time.” (p.27). We were drawn to this mode of working to explore our supervision practice, as we felt it mirrored the change process of learning to become an art therapist. The one-canvas process has a specific art-based structure, whereby through the sustained engagement with art-making on one surface the artistic images are explored and transformed (Miller, 2022).

The process also values the time that lapses between each reworking of the surface; this period can be a space for a reflective pause (Miller, 2022) that contributes to the emergent meanings and understandings. To capture this process of transformation over time, sequential documentation of the process is vital and photographing or recording each distinct layer is recommended (Miller, 2012). Our arts-based process was supported by the structure detailed below.

Table 1. Arts-based inquiry procedures.

A materially diverse one-surface process

As a group of educators, we were inspired by Miller’s (2012, 2019, 2020, 2022, 2023) extensive work with the one-canvas process. We were also interested in incorporating our professional experience as art therapy teachers, where we often emphasise varied material experimentation. We were curious to experiment with our understandings of the inherent qualities of diverse media, to explore the possibility of synergy between our lived experience as educators through the one-surface process we deeply value.

As a foundation for our understanding of the therapeutic dimensions of materials we were informed by the Expressive Therapies Continuum (Graves-Alcorn & Kagin, 2017; Hinz, 2019; Kagin & Lusebrink, 1978), in an attempt to emphasise the powerful properties of diverse making and material engagement. In acknowledgement of this interest and a desire to embrace a structured one-surface process, team members came together and constructed the four prompts below to structure each layer of our creative process:

Layer one: How do you understand the role and the function of the art-making process and the art object in the supervision exchange?

Layer two: What is your stance and orientation as the group supervisor when holding complex and dynamic placement material?

Layer three: How do you understand what the responsibilities are of the trainee art therapist in contributing to an educational learning environment of group supervision?

Layer four: What is the function of the group learning environment in contributing to the unique dynamic of supervision?

Incorporated into this process was the invitation that team members engage with a spectrum of materials that best resonated with their understanding of and response to the question and that material choices could change over time.

Project team members

The project team (artist-authors) was made up of five qualified art therapists who were working as teaching staff in the Master’s program at the time. As a collective, clinical experience ranged from between six to 15 years in diverse settings working across the lifespan with infants, children, young people and adults and in a range of contexts, from inpatient, community and private practice.

All members of the project team have taught into the supervision component of the placement program, either at first-year or second-year level of the Master’s program. The level of teaching experience of each team member ranged from six to eleven years. As a group of art therapy colleagues, we have shared values as educators and clinicians, deeply valuing person-centred ethics and experiential learning modes.

Metaphor, symbol and weaving an emergent narrative

The following section details the one-surface process. As we were interested in an integrative way of exploring our practice, where we embed process-oriented ways of meaning-making (Lett et al., 2014) this section includes artist-author narrative and response writing, interwoven alongside imagery and frameworks of understanding from the literature. Subheadings encapsulate emergent themes of each layer.

Layer One: Vulnerability, contained mess and potential

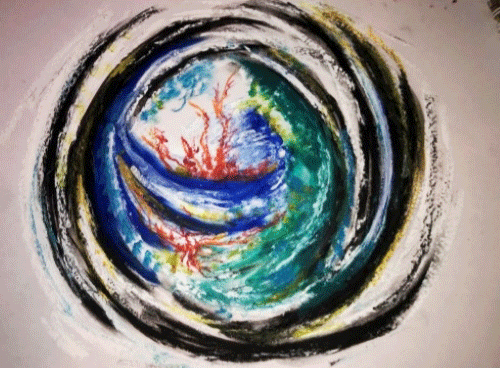

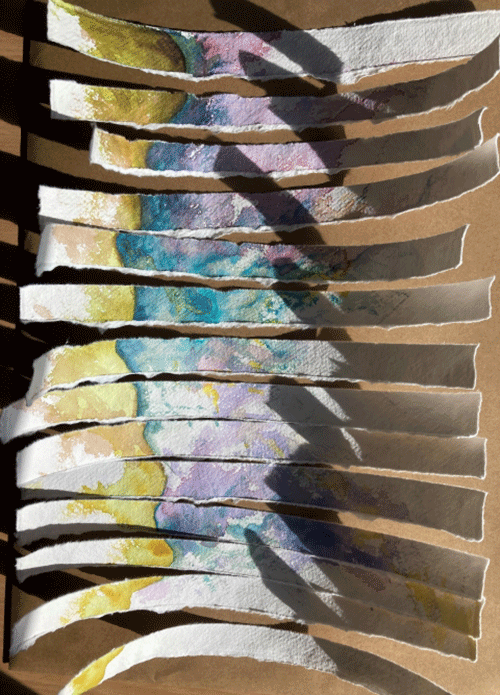

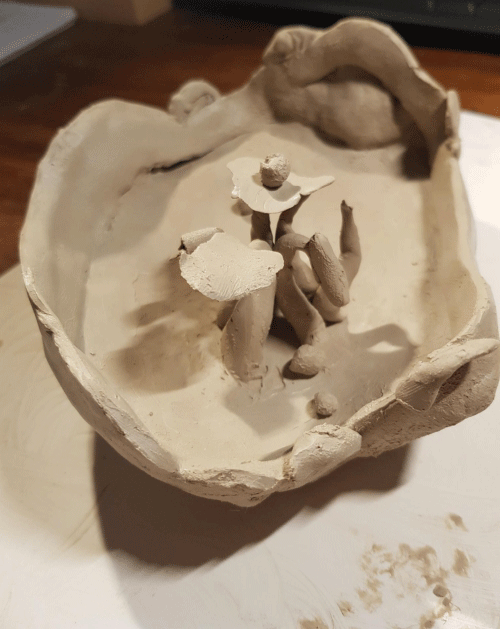

Figure 1. Art-based responses: How do you understand the role and the function of the art-making process and the art object in supervision within the Master of Art Therapy?, 2023, mixed media, variable sizes.

In response to this prompt, dwelling upon the function of the art-making process in supervision, artist-authors noted the carefulness in curating a space for their creative process; some noted high energy, “excitement to have this time to make”. Artist-authors worked for diverse lengths of time, on average for an hour. In this first phase of making, materials were chosen for their capacity to regulate the maker but also to respond to the question with symbolic fit and alignment. As Author 4 remarks of soft pastels:

... the repetitive layering of the pastels supported me to explore this question. The intensity of the layering was evident towards the ‘core’ of the image – the desire to blend, overlay, ‘stretch’ and connect and make further marks was strong… I noticed myself shifting from working ‘within’ the piece – to extending the outer layers… my hands welcomed this transformation.

Having the capacity to choose a variety of materials met the diverse psychological, kinaesthetic and cognitive needs of team members. Artists worked with a range of materials. Author 2 reported that she felt “vulnerable, the materials are not ones I often use …The paint fumbled across the surface, being uncomfortable and being able to fumble” and others described the process of making a “mess” (for example, Author 5). These varied experiences seemed to support thinking around the productive role of discomfort generated in supervision learning.

There was consensus that the art practice of the supervisor was vital to their capacity to consistently offer this as part of the supervision process. When understanding the offering of the art-making process in supervision themes emerged such as “going deeper” and offering “potential space” (Winnicott, 2012) to rework personal material through the professional lens. This was embodied by the images, such as the gesture of “stretched line”, the “weight” of the components of the clay piece and the “surfaces” of the box form interacting with each other.

Layer Two: The power of the interim period in supporting transformation

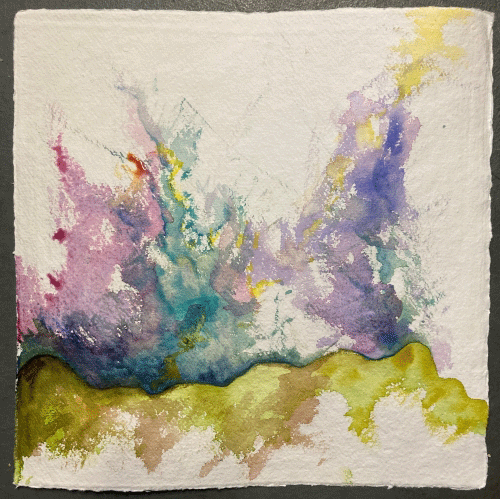

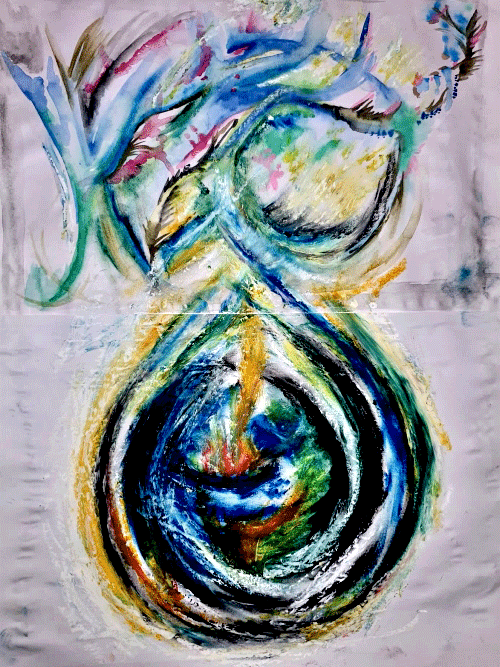

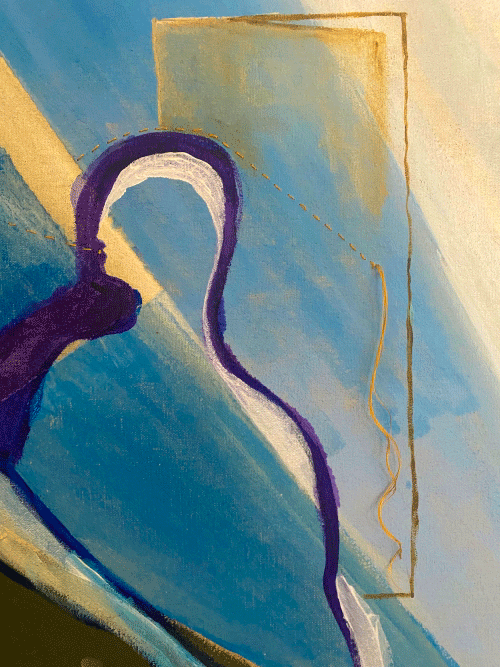

Figure 2. Art-based responses: How do you understand the stance and orientation of the supervisor in holding complex and dynamic placement material?, 2023, mixed media, variable sizes.

During the second sitting, in response to the prompt to reflect on the supervisor stance, the artist-authors became aware of the impact of the interim phase. As Miller (2022) notes, this gap or pause between active art-making “can be understood as both a noun; a thing that can be acknowledged, and a verb; an action.” (p.24). Artist-authors noted the functional role that this pause played in allowing the impact of the image to “sink in”. When coming together, the interim period was described as “refreshing and freeing” (Author 5) and the opportunity to rework the image was understood as a way of “having another look” (Author 3) at the original work, noticing how the materials had settled since the original creation, as makers noted “complexity and resistance” (Author 5) when reworking the object.

Key words at this phase seemed to be linked by themes of transformation: reconstructing, deconstructing, reframing, reworking, revisiting. Author 1 said she “had a desire to tear the image” to make the work manageable, as she tore the watercolour image purposefully into strips. The description Lawson offers us of their making process resonates: “The resultant finger-long canvas pieces felt manageable, their bandage-like qualities presenting me with an opportunity to realign, reset, and rediscover….” (Green et al., 2022, Wendy Lawson waits section). When the work was deconstructed, the pieces were experienced as being “held in a liminal state of coming apart and coming back together” (Author 1).

Interestingly, for three artist-authors, there was a discomfort or a “dislike” of the image; this seemed to emerge in the scan of the image when symbolic qualities were experienced as “dominant” or misaligned with their view of supervisory practice. When reconciling and processing this, artist-authors were able to move into a place of sense-making through the transformation of the object, as Author 4 notes:

My initial response was uncomfortable… I struggled to work with the dried clay… I turned the piece and it became this shell-like space. There was an opening up of, making space, holding and letting go. I imagined almost even standing back as a gesture – in relation to the student and the material.

Here we observed the productive role of the disturbing image – “it is work with disturbing images that best demonstrates the value of opening to the expressiveness of an object… if an image… agitates the person who generates it, it is likely conveying a message that needs attention” (McNiff, 2004, p.96). What we did observe was the power to reengage with this material through the one-surface process. The artist-authors were empowered to rework complexity through revisiting this discomfort with media use. The opportunity to work with the “discomfort” spoke to their supervisory belief that the witnessing of difficult “parts” supports a more integrated and authentic clinical identity.

Each artist-author noted the agency, empowerment and enhanced self-awareness that came from reworking different parts of the image into a new form. In this way, we identified how the artist was able to be fully open to the image, be present with it and give space to understanding it (McNiff, 2004). Having the one-surface to return to offered in-depth opportunities to forge this empathetic understanding of the material being explored.

These reflections also revealed that through the symbolic and material engagement we understood the art therapy supervisor stance to be in constant “discourse with the art-making” (Author 2) and that the art-making could be utilised to support a way of connecting with the student to support individualised “growth and learning” (Author 4). Modelling, mentoring and teaching seemed important. It was noted that it is vital to show the importance of being able to “let go and open out… to be able to hold a problem lightly and remain open to new knowledge and trust (more) in the creative process” (Author 3). Whilst we appreciated that growth and change occur in supervision, the supervisor as “witness” (Byrne & Fenner, 2023; Learmonth, 1994) to this change was vital to embed new learning. This was also seen as a departure from teaching clinical skills or theory, as in supervision we teach a process and facilitate a space where students can explore and discover their own internal growth. We move from imparting knowledge to creating an environment that permits the discovery of knowledge of self.

Layer Three: Assemblage and reconstruction as a potential space

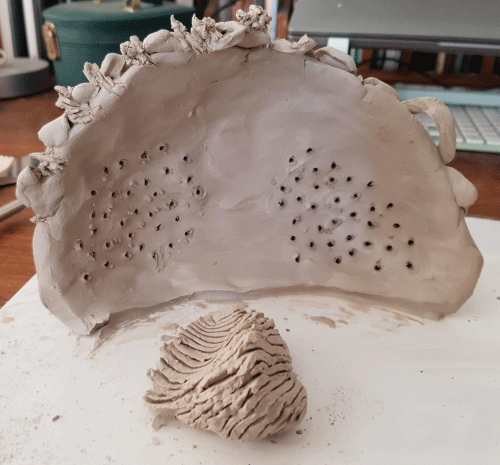

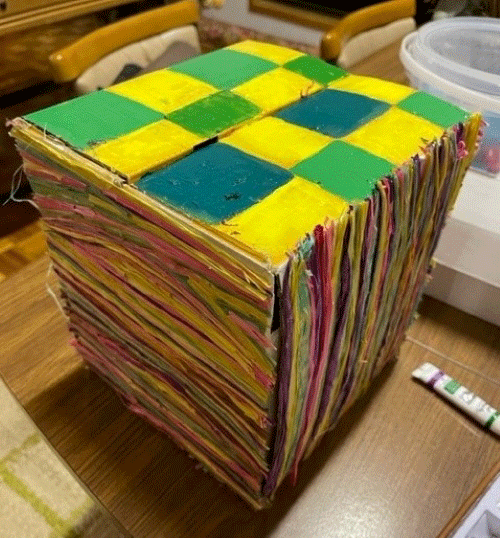

Figure 3. Art-based responses: Exploring the supervisor’s understanding of the responsibilities of the trainee art therapist in contributing to the educational learning environment, 2023, mixed media, variable sizes.

At the third time point, the artist-authors noticed that the making began slowly, perhaps as the invitation to actively contemplate what we perceived to be the student supervisee’s responsibilities felt complex. We identified that in educational supervision the student is permitted to be “messy” and struggle to locate the “edge” of the learning. However, with the skilled supervisor’s support, the student is “held in the professional ethic of the teacher”. This ethic adds the dimension of how group dynamics happen, scaffolding the developmental terrain and how the trainee is cared for in the process of their emerging professional identity. Within educational supervision, the student is supported through the necessary discomfort of growth, the limits of which the teacher must sensitively navigate.

We identified the “tension” as essential to productive learning, as the student navigates away from classroom learning and towards professional development. Interestingly, Miller (2022) described a tension in the one-surface process, noting that the “layering process befriends and makes room for tension, the messiness of not knowing” (p.29). The artist-authors’ experience of tension was often understood as an embodied sense to move towards structuring and reinforcing the image, to create changing supports in the image and a strengthened form.

As one artist-author observed they wanted to “connect, glue onto a larger piece of paper … engagement, openness and interplay between vulnerable and professional” (Author 4). This was also where Author 5 moved into the action of lacing, weaving and interlocking the strands of paper together. These were understood as acts of “assemblage and piecing together” (Author 5). We wondered collectively about the supervisor’s role in crafting a safe enough group environment to support the new assemblage of a cohesive professional self.

Layer Four: Experiences with diverse materials over time

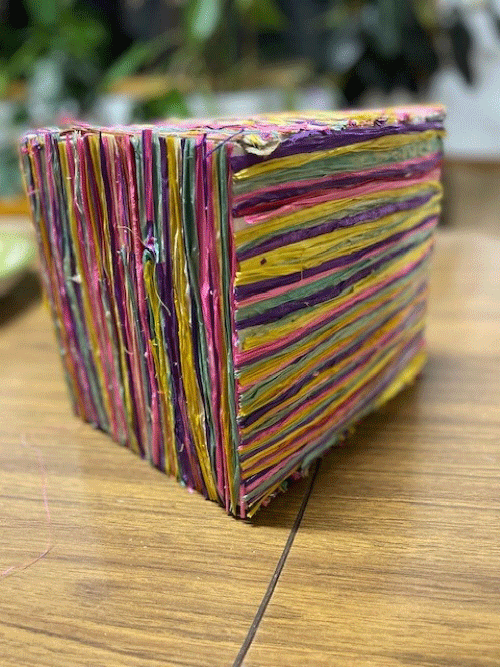

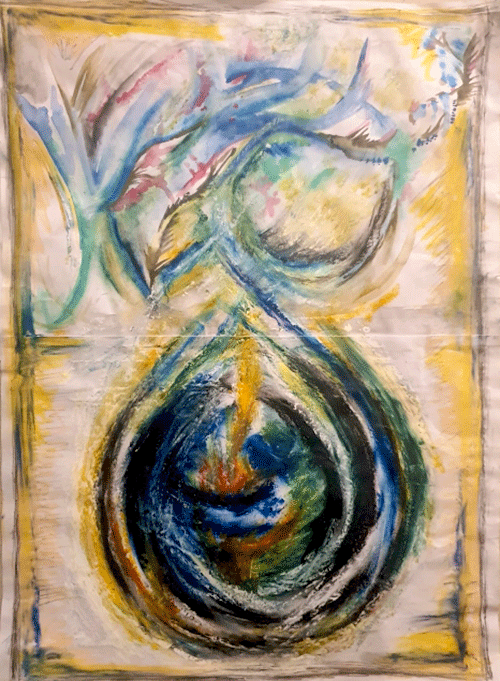

Figure 4. Art-based responses: How do you understand the function of the class-group in contributing to the unique dynamic of supervision?, 2023, mixed media, variable sizes.

During this final and slower phase of reworking the surface, contemplating the role of the class-group dynamic, there seemed to be two key shifts – the “addition of parts” and also the felt need to “change perspective”. For example, “reconstituting (adding water) and carving out” parts of the clay object to make room for new additions/figures, “spinning and turning” the paper to work from another vantage point and turning the canvas over to “work on the underside”. Some artist-authors also emphasised “adding”. One “added borders” – painting in a border or additional definition to demarcate more clearly a door to move through and clarifying a boundary. One added her own response art from a final supervision class; these longer strips were laced into the woven collage and were “left in movement” extending beyond the original tighter weave, “lengthy, soft and draped outward”.

In reflecting on the works as a whole, we noted the increased presence and introduction of crafting techniques. For some this was the introduction of craft materials, such as embroidery threads and fibres to sew (Authors 2 and 5). For others, it was the technical acts of crafting that were progressively applied, such as weaving (Author 1). Talwar (2019) observes how “crafting becomes a transformative experience to enact a framework of ‘touch and relationality’” (p.21). The introduction of these materials and techniques resonated with their idea that crafting can symbolise relational meaning and connection. As supervisors, we listen and hold subjugated and hidden stories of student’s lived experiences much like the craftwork holds the expression and communication of lived experience in marginalised groups (Talwar, 2019).

Exploring this shifting material choice further, Author 2 began to stitch and sew, noting the kinaesthetic dynamic of repetitive piercing movements – similar to what Wolk and Bat Or (2023) observe as, “a feeling of calmness … through the repetitive movements involved in embroidery, the tactile quality of the embroidery on the fabric, and the sound of the needle piercing the fabric, as well as the need to concentrate.” (p.9). We wondered about this repetitive “returning to” the image, as the thread moved into and out of the image. This act captured some of the embodied experience of learning in supervision, that it is a process of moving towards new boundaries both personally and professionally in the workplace and the classroom.

Figure 5. Author 2, Integration of thread and sewn form (detail), 2023, mixed media, variable sizes.

This was also seen in the collage woven form of Author 1:

I weave and piece together this image, I am making, forming, bringing together…. Looking back on the process of making this work I notice how it has been pulled apart and deconstructed… how will they fit back together? …Once I’ve taken my image apart, I start weaving…. I note some pieces are now too short – as the piece expands as I move more and more paper into the weave. I have a rhythm now, as I collect the bits that fall off, and nudge the other pieces into place…it holds together.

To remain intact through the turbulent learning experience – of simultaneously looking inward and outward – the pieces come back together and apart in different ways. In the fourth layer phase, we also reflected on the restorative experience of supervision for professionals and students. An unexpected aspect of this group reflection has been the reconnection with a deeply valued practice space as a team of supervisors. Collectively, each project member spoke of the process as a sustaining force during busy periods of work, where traditionally they might expect to feel more depleted. The routine of reworking the one surface seemed to offer a platform that felt manageable too, where they could revisit something that was in progress. The meetings between the artist-authors provided a motivating force to reconnect through creative expression, but also to witness the deep care and thought of the team’s supervisory practice.

Concluding remarks

The one-surface process generated emergent insights that enrich our approach to group supervision learning and to the supervisory role. Echoing findings from other studies, the artist-authors found the arts-based process enlivening and affirming of arts-based supervision models (Brown & Wilson, 2023; Lis-Ron et al., 2024, 2025; Miller, 2012, 2019, 2020, 2022, 2023; Miller & Robb, 2017; Robb & Miller, 2017). By adapting Miller’s (2012, 2020) one-canvas process to incorporate the selection and sequential layering of diverse materials upon one surface, the material properties of the art-making functioned as an active symbolic language. Materials were experienced as regulating and generative, reflecting the relational dynamics of group supervision. Within co-created boundaries that remain simultaneously solid and flexible, supervisee, supervisor and art-making come together in ways that can be reconfigured and transformed over time, crafting a safe enough environment of professional care within which learning may occur.

We are left wondering whether, in light of this arts-based inquiry, there is an opportunity to contemplate an ethic of care for supervision. Meaning, one in which the clinical dimensions of trainee art therapists’ professional development are relationally scaffolded. We are familiar with the notion of ‘ethics of care’ in our clinical practice (McAuliffe, 2023; Tronto, 1993). This stance values the relational-emotional dimension of practice within a culturally humble frame, as operationalising the way in which the art therapy process meets the needs of our clients. In addition, we are often curious about the triangular conversation that unfolds, exploring fully the responsibilities of the therapist, the role of the image and the client’s experience of safety and meaning.

From this project we are interested to see if we can bring this orientation into the educational supervisory experience, pondering how a ‘supervisory care ethic’ might be defined and enacted in the education of art therapists. From our learnings we can see that the supervision encounter is directly informed by the supervisor’s clinical acumen as an art therapist – this foundation forms the base from which supervisory thinking emerges.

However, it also involves establishing a safe enough process and structure to allow the student to learn for themselves about themselves. Educational supervisors are required to actively model best practice, restorative self-development, and administrative and ethical considerations in supervision, while providing direct and complex feedback in the context of assessment requirements. This is a decisional process that educational supervisors continuously navigate, holding in mind not just learning edges but also the structure and space that is most conducive to learning for the individual and the group.

We have learnt to do this most effectively by holding in mind our own mentors and teachers. We carry their internalised voices that have shown us how to gently hold our own vulnerabilities, messiness and potential as we grow into professionals learning through our own experiences of feedback and self-assessment. The art-making helps both supervisors and students make sense of the subjective and individual growth that occurs in the transition from student to professional art therapist. It is clear that the art-making process and the object itself play an essential and vital function in the supervision of trainee art therapists and that this process has dual roles of both supporting psychological safety and regulation in the classroom, but also as a surface from which the student can process the “unsayable” (Visse et al., 2019).

The creative rhythm of the one surface led us to encounter important learning moments of resistance, resolution, reconstruction and transformation. In addition, by incorporating a diverse range of materials we were able to make choices around how we worked with that process. We could claim moments of pause to reflect through regulatory media or we could stretch and push our learning by actively working with materials that supported creative risk-taking, productive discomfort and unfamiliar experience. In reflecting on this experience, we feel that the one-surface process has been both supportive of professional reflection but also offers a framework for student learning.

Consent

Consent to participate – Not applicable. All group members agreed and approved the text and images.

Consent for publication – All authors consent to publication

Authorship and conflict of interest

Tess Crane and Kate Richards developed the project topic and structure as part of a scholarship of teaching and learning inquiry with the Master of Art Therapy program at La Trobe University. All authors contributed to the key ideas presented in the article, either through written contributions or through participation in team meetings, generation of artworks and contributing reflections. Crane wrote summary notes from the reflective meetings and Crane and Richards synthesised the salient themes. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript which Crane then finalised. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Brown, A. & Wilson, M. (2023). Working with layers: A heuristic study utilising single-canvas art-making to illuminate personal responses of the therapist. JoCAT, 18(1). https://www.jocat-online.org/a-23-brown

Byrne, L., & Crane, T. (2021). What is left of the studio, in the absence of a room to share? Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 12(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah_00077_1

Byrne, L., & Fenner, P. (2023). Emanation in creative practice: Exploring the impact of McNiff’s construct of witnessing in an Australian setting. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 14(3), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah_00145_1

Cahn, E. (2000). Proposal for a studio-based art therapy education. Art Therapy, 17(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2000.10129696

Crane, T., & Byrne, L. (2020). Risk, rupture and change: Exploring the liminal space of the Open Studio in art therapy education. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 69, 101666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101666

Deaver, S.P. (2012). Art-based learning strategies in art therapy graduate education. Art Therapy, 29(4), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.730029

Deaver, S.P., & McAuliffe, G. (2009). Reflective visual journaling during art therapy and counselling internships: a qualitative study. Reflective practice, 10(5), 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940903290687

Fenner, P., & Byrne, L. (2019). Is all art making ethical? Dilemmas posed in the making of response art by Australian art therapy trainees. In A. Di Maria (Ed.), Exploring ethical dilemmas in art therapy (pp.332–338). Routledge.

Fish, B.J. (2008). Formative evaluation research of art-based supervision in art therapy training. Art Therapy, 25(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2008.10129410

Graves-Alcorn, S., & Kagin, C. (2017). Implementing the expressive therapies continuum: A guide for clinical practice. Taylor & Francis.

Green, D. (2020). Mortification meanderings: Contemplating ‘vulnerability with purpose’ in arts therapy education. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 68, 101629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101629

Green, D., Dalton, H., Lawson, W., Marks, K., Richardson, A., & Tapper, H. (2022). Once upon a glowing rabbit story that leads home… Journal of Creative Arts Therapies, 17(1), 1–28.

Hinz, L.D. (2019). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy. Taylor & Francis.

Kagin, S.L., & Lusebrink, V.B. (1978). The expressive therapies continuum. Art Psychotherapy, 5(4), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-9092(78)90031-5

Learmonth, M. (1994). Witness and witnessing in art therapy. Inscape, 1, 19–22.

Lett, W., Fox, K., & von der Borch, D. (2014). Process as value in collaborative arts-based inquiry. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 5(2), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.5.2.209_1

Lis-Ron, V., Gavron, T., & Bat-Or, M. (2024). The One-Canvas Model as a visual container for the researcher-supervisor. International Journal of Art Therapy, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2024.2313719

Lis-Ron, V., Gavron, T., & Bat-Or, M. (2025). Impact of EDPP supervision on creative arts therapists’ professional development, art-working alliance, and openness to experience. Art Therapy, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2025.2490413

McAuliffe, D. (2023). An ethic of care: Contributions to social work practice. In D. Hölscher, R. Hugman, & D. McAuliffe (Eds.), Social work theory and ethics (pp.1–18). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3059-0_18-2

McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Shambhala.

McNiff, S. (2008). Art-based research. Jessica Kingsley.

McNiff, S. (2018). Doing art-based research: An advising scenario. In R.W. Prior (Ed.), Using art as research in learning and teaching: Multidisciplinary approaches across the arts (pp.77–90). Intellect Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv36xvzf5.10

Miller, A. (2012). Inspired by El Duende: One-canvas process painting in art therapy supervision. Art Therapy, 29(4), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2013.730024

Miller, A. (2019). Multiple roles in art therapy supervision: Using El Duende one-canvas process painting. In A. Di Maria (Ed.), Exploring ethical dilemmas in art therapy (pp.339–351). Routledge.

Miller, A. (2020) One-Canvas Method: Art making that transforms on one surface over a sustained period of time. Expressive Therapies Dissertations. 94. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations/94

Miller, A. (2022). El Duende one-canvas art making and the significance of an interim period. Art Therapy, 39(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2021.1935062

Miller, A. (2023). The innovative essence of the El Duende one-canvas method. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 14(1), 27–45.

Miller, A., & Robb, M. (2017). Transformative phases in El Duende process painting art-based supervision. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.009

Moon, B.L. (2003). Essentials of art therapy education and practice (2nd ed.). Charles C. Thomas.

Potash, J.S., Bardot, H., & Ho, R.T. (2012). Conceptualizing international art therapy education standards. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(2), 143–150.

Robb, M., & Miller, A. (2017). Supervisee art-based disclosure in El Duende process painting. Art Therapy, 34(4), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2017.1398576

Skaife, S., Jones, K., & Pentaris, P. (2016). The impact of the Art Therapy Large Group, an educational tool in the training of art therapists, on post-qualification professional practice. International Journal of Art Therapy, 21(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2015.1125382

Talwar, S. (2019). Feminism as practice: Crafting and the politics of art therapy. In S. Hogan (Ed.), Gender and difference in the arts therapies: Inscribed on the body (pp.13–23). Routledge.

Toll, H. (2022). Art therapy education: Embracing a perpetually changing world (Éducation en art-thérapie: S’adapter à un monde en perpétuel changement). Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 35(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/26907240.2022.2083896

Tronto J. (1993). Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge. https://doi-org.ez.library.latrobe.edu.au/10.4324/9781003070672

Van Lith, T., & Bulosan, J. (2022). Creating our own suspension bridge between practice and evidence. Art Therapy, 39(3), 119–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2022.2113728

Visse, M., Hansen, F., & Leget, C. (2019). The unsayable in arts-based research: On the praxis of life itself. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406919851392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919851392

Westwood, J., & Linnell, S. (2011). The emergence of Australian art therapies: Colonial legacies and hybrid practices. Art Therapy Online: ATOL, 1(3), 1–19.

Winnicott, D.W. (2012). Playing and reality (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Taylor & Francis.

Wolk, N., & Bat Or, M. (2023). The therapeutic aspects of embroidery in art therapy from the perspective of adolescent girls in a post-hospitalization boarding school. Children (Basel), 10(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061084

Authors

Tess Crane

MAT, GradDip(Psych), BAppSci(Psych), AThR

Tess is a qualified art therapist, PhD candidate and academic staff member of the Master of Art Therapy program at La Trobe University. She is currently pursuing PhD studies in the area of art therapy and perinatal mental health. She has extensive clinical experience working in inpatient and acute adult mental health settings and has developed an interest in delivering group art therapy in a range of settings, including parent-infant work, working with clients living with eating disorders and complex trauma. As an educator, Tess is dedicated to delivering high-quality, engaging training and contributes to the field through art-based inquiry and published scholarship.

Kate Richards

MAT, Dip(CA), BA(Psych), BA(ArtHist), AThR

Kate is a registered art therapist (ANZACATA) and lecturer in the Master of Art Therapy program at La Trobe University, Melbourne. For over 15 years she has worked with children, adolescents, and families with diverse lived experiences of complex trauma, integrating art therapy with neuroscience-informed approaches, across community and hospital settings. Her recent practice has focused on establishing an Open Studio program for young people and providing dyadic art therapy for young people and their caregivers after family violence. Additionally, trained as an art curator, Kate explores the intersections of emotion and creativity through exhibitions and arts-based projects, grounding her commitment to art and health in her own art-making.

Pam Hellema

MAT, BA(FineArt), AThR

Pam is an art therapist, supervisor and lecturer with the Master of Art Therapy at La Trobe University. Passionate about supervision, Pam has supported emerging art therapists for over 15 years. Her integrated practice includes training in specialist perspectives such as Internal Family Systems Therapy, Narrative Therapy, Music Therapy, Sand and Play Therapy. One of Pam’s key achievements has been to pioneer the art therapy program within the Alfred Addiction and Mental Health service. Pam has since worked in child and adolescent mental health, acute paediatric care, family reunification and youth residential support services.

Carmen Millic

MAT, BArtTh, AThR

Carmen is an art therapist, lecturer and artist who is passionate about furthering the arts and health movement in Australia. Her experience as an art therapist includes working with mental health, trauma, spiritual care, and neurodiversity. At La Trobe University Carmen is responsible for maintaining and growing the clinical placement relationships within the Master of Art Therapy program, delivering a positive placement experience for students and teaching into the clinical supervision subjects. As an artist, Carmen’s creative practice is underpinned by a curiosity that explores the interplay between the arts and human flourishing; and how engaging with the creative process can unveil that which may not necessarily be seen or experienced through words alone.

Sally Goldstraw

MAT, DipTransATh, BBSc

Sally worked in the family violence sector for over ten years with children and women recovering from the impacts of trauma, and established ‘Van Go’, a mobile creative therapies program. She has worked for local and state government, utilising creativity in community capacity building. She taught for seven years at La Trobe University in the Master of Art Therapy course. She lives in Halls Gap and has been providing Open Studio sessions for well-being as the community recovers from devastating bushfires. Currently, Sally is providing supervision to creative therapists as well as pursuing an artistic life that includes painting, textiles, and ceramics.