Open Access

Published: September 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.2

Word count: 5,173

About the author

Using digital art to explore my experience of sepsis: An arts-based autoethnographic inquiry

Susannah Morrison

Abstract

This article utilises arts-based autoethnographic research to explore the experience of sepsis through the lens of the author’s lived experience. It recounts the chronological timeline from the first signs, hospital experience, intensive care treatment, to the recovery with post-sepsis syndrome. This arts-based research approach is expressed with digital art created in Procreate. Each digital art expression highlights the therapeutic possibilities within the arts therapy field as a valid and accessible modality for creative expression, reflecting on experiences within healthcare treatment and recovery. Identifying the signs of sepsis and awareness of sepsis survivors’ experiences with post-sepsis syndrome continue to be ongoing issues that impact the critical treatment of sepsis and the support during recovery. Documenting survivor experiences of sepsis through arts-based autoethnographic research can both add to knowledge of managing sepsis patients and assist survivors in processing and finding their pathway through recovery.

Keywords

Sepsis, post-sepsis syndrome, ICU, critical illness, digital art, Procreate, arts-based autoethnographic inquiry

Cite this articleMorrison, S. (2025). Using digital art to explore my experience of sepsis: An arts-based autoethnographic inquiry. JoCAT, 20(2). https://www.jocat-online.org/a-25-morrison

Listen to the podcast

Introduction

This article is structured around the chronological timeline of my experience of sepsis. It recounts the lead-up, my first signs of sepsis, experience in the hospital emergency department, surgery, treatment in an intensive care unit (ICU), transition back to a general ward, recovery with post-sepsis syndrome, and the path forward after recovery.

Sepsis is “a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by an exaggerated host response to infection” (Arora et al., 2023, R613). Although completely preventable, 27% of hospital admissions for sepsis result in mortality, with this increasing to 47% for intensive care unit admissions (World Health Organization, 2020, pp.12,16). Sepsis is “the most common cause of admission and death in the intensive care unit” (Dobson et al., 2024, p.1).

Recognising the signs of sepsis and responding quickly with antibiotic treatment can save lives and prevent mortality (Gyawali, 2019). In recognition that knowing the signs and administering treatment are time sensitive, this article will cast a spotlight on the signs of sepsis that I experienced that led to treatment, including fatigue, pain, nausea, fever, changes in heart rate, blood pressure and breathing, as well as mental confusion. It should be noted that this article is not intended to be a diagnostic tool for sepsis as not all patients present with the same signs, and there are other conditions that have similar presentations to the early stages experienced in sepsis (Olander et al., 2023).

Research methodology

This article utilises arts-based research (ABR) which Boyd and Barry (2024) define as documenting the insights, relationships, and processes that emerge from using creative modalities. The ABR documents my recovery from sepsis during which I experienced post-sepsis syndrome (PSS) which affects 50% of sepsis survivors (Smith-Turchyn et al., 2025, p.9). PSS is more prevalent in patients who have experienced more severe sepsis or have other health conditions (Leviner, 2021). Although there are some variations in how PSS is individually experienced, commonalities exist, including long-term fatigue, challenges with memory and cognition, and decline in psychological well-being (van der Slikke et al., 2023).

While experiencing PSS, I was looking for a more accessible creative modality to conduct my ABR and chose to use digital art. The inclusion of digital art within the arts therapy kit of materials and modalities can allow for a broader scope of clients, who may not engage with more traditional materials, to access and participate in arts therapy (Zubala et al., 2021). The sketching, drawing, and painting application used to create digital art expressions in this article was Procreate. Throughout the article, there are descriptions of how the tools from Procreate were used to support the creative expression process.

In addition to arts-based research, I have also employed an autoethnographic approach. This methodology situates the person as researcher in relationship to a cultural context to examine beliefs and values, interpersonal and personal encounters, and the insights that emerge from these (Ellis et al., 2011). As I have chosen to present this through arts-based autoethnographic research, this article will flow between the lived-experience reflections, digital art and supporting literature. Furthermore, this article will use both present and past tense to honour the authentic voice of the experience, the arts, and the researcher.

The lead-up to sepsis

I had finally seen the light at the end of the tunnel. My arts therapy studies were coming to a close and my study placement had just ended. The final stretch involved managing multiple deadlines and finalising assignments while also juggling my own work and personal life. I felt emotionally and physically exhausted from having a life load exceeding my capacities and knew that the end had come at the right time. I was on the verge of academic burnout from my studies, which Madigan et al. (2023) assert can impact health and wellbeing with feelings of exhaustion, reduced motivation, and lower self-confidence towards academic tasks.

Throughout my placement, I was consistently unwell with viruses and infections, and I perceived this as an initiation into the world of working in community centres; I hoped that constantly being unwell would ease with time. This is generally the case, according to Biggs and Littlejohn (2022), who note that prior immunity has been shown to reduce severity experienced in future illnesses. However, Biggs and Littlejohn also note that other factors that influence this outcome may include the individual’s general health (2022). I felt such relief when I finished my placement, as I could finally have some rest to rebuild my health. This relief, however, was short lived as my body began to show the first signs of sepsis. This is where my story starts.

The first signs

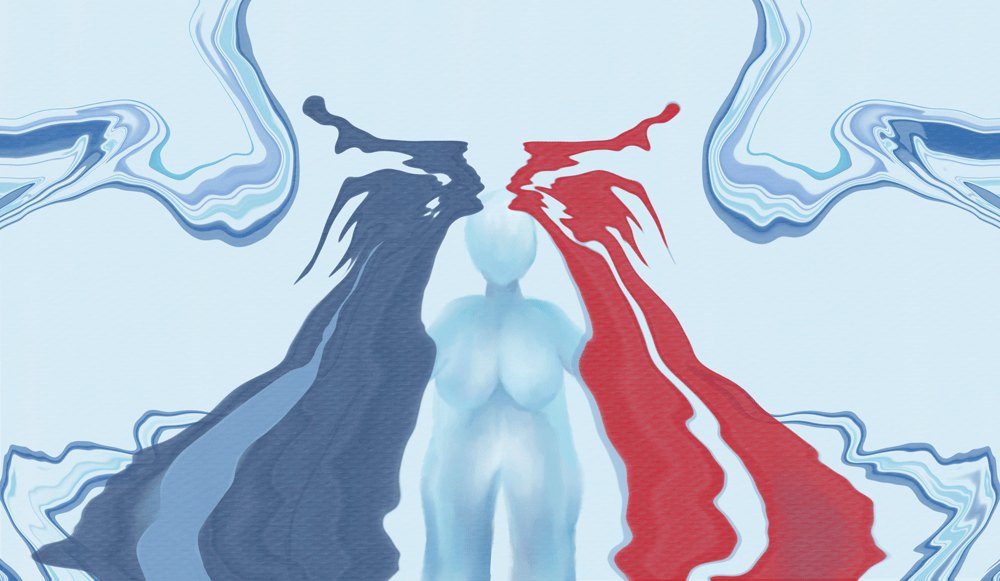

The research begins! I am at home, recovering from sepsis on the couch with my digital tablet as a companion, reconnecting with my experience of my first signs of sepsis. I start with applying paint strokes, as seen in Figure 1, very aggressively and with a sense of immediacy, to create quickly and overlap the colours on my digital canvas. My first sign of the start of sepsis, I now know, was that I had woken up in the middle of the night with a sudden onset of excruciating pain in my abdomen. I took this first sign to the digital canvas, focusing on the sensation of pain I had felt. It needed the Liquify tool to capture the essence of these paint strokes meshing, then pulling apart to form the gnarling pain experienced in my abdomen. I remember feeling vaguely unwell in the few days leading up to sepsis, and how I was ignoring my body’s need to rest to get through the day-to-day demands. I now ponder how Abram’s (2010) concept of mind and body was reflected in the way my ‘thinking mind’ was distancing from my ‘sensing body,’ and dismissing the intelligence coming from this. I was not ready or willing to be present with this until my body was screaming in pain.

Figure 1. Susannah Morrison, Pain, 2025, digital art.

Emergency care

Deep down in my bones I knew this pain was indicating something serious. I called the ambulance. Unfortunately, they were experiencing a ramping crisis. My only symptom, severe abdominal pain, was not enough for them to prioritise me as critical. I had to call my mum to drive me to the hospital. Arriving at the emergency triage desk, I vomited and lost bladder control at the same time. Vulnerability and shame came to visit. I was sitting in my own urine, smelling the residual vomit emanating from my top, and still in agony from the absolute pain. About an hour had now passed between waking and being triaged in the waiting room.

I remember thinking, “Gosh, it’s so cold”. The shivering chills began soon after sitting down in the waiting area. My muscles were tense, the sensation was overpowering, dissonant, and discombobulating. The background of the canvas seen in Figure 2 uses hues of blue reminiscent of ice paired with the Liquify and Symmetry tools to recreate the experience of these reverberating chills being an undercurrent in the space around and within. This was mirrored with the representation of my body. There, in hospital on a warm spring night, three blankets wrapping me, I still felt so cold, like I was in Antarctica. I continued to explore with the Symmetry tool, experimenting with this concept of these feelings coexisting, then the two entities emerged, dominating my body. Mum just thought I was in shock, yet chills and shivering accompanying the fever can also be early signs of sepsis (Van Dissel et al., 2005).

Figure 2. Susannah Morrison, Chills, 2025, digital art.

Acute care

I remember the emergency room being overwhelmed with patients, and the staff busily attending rounds and checking different things each time. A nurse commented regarding my blood pressure and heart rate. By the third round of observations, I was escalated to the acute care emergency area with concerns over my blood pressure, heart rate and fever. It had now been approximately three hours since waking with abdominal pain.

Fortunately, I was able to see a doctor soon after and we discussed how I was already scheduled to come in the following week for a surgery to remove a suspected ovarian cyst. However, this pain I felt was not in my pelvis; it was around my belly button. The doctors continued to point to my pelvic area as the site of pain, which is common in ovarian torsion due to the rotation of the ovary reducing blood flow (Bridwell et al., 2022), but I was pointing to my belly button when showing the doctors where I felt the pain. They organised a pelvic ultrasound to determine whether ovarian torsion was present, and nothing conclusive was found. However, they still scheduled emergency surgery for a suspected ovarian torsion, which, according to Bridwell et al. (2022), is also a medical emergency.

Even though the doctors were responding seriously to my presentation of symptoms, I still felt confused, misunderstood and that my explanation of where I was feeling the pain was being ignored. It was also noted in my discharge summary that I experienced acute pelvic pain (Hospital, personal communication, 24 December 2024). As I step back into this feeling, I am reminded how our body can be silenced due to not having the ‘word privilege’ to speak for itself, which Caldwell and Bennett Leighton (2018) explain sets the body at a disadvantage when there is pain experienced.

Pre-surgery

The shivering continued as I was taken to preoperative. Experiencing chills that manifest as shaking or shivering are often the body’s way of changing body temperature to fight infection (Taniguchi et al., 2013). I remember the pervasive shivering of my body, particularly my teeth, which were reminiscent of one of those ‘chattering teeth’ toys that use a wind-up mechanism to transfer kinetic energy to create the chattering action. I felt alone and afraid waiting in preoperative by myself. I requested something to relax my teeth, as I just wanted it to stop. I transferred this dissonant moment to the digital canvas, as seen in Figure 3. I was curious about how to express this dynamic movement within a still image. I found myself playing with Motion Blur and Duplicate tools, along with object and layer opacity, to speak to this experience. Returning to my experience, the medical staff finally administered the relaxing medication on the operating table, and then the surgery began. It had been over eight hours since I woke up with abdominal pain.

Figure 3. Susannah Morrison, Chattering Teeth, 2025, digital art.

Post-surgery

The timeline starts to get more confused now as the complications began to escalate. I awakened from surgery with my arm tightly wrapped in a compression bandage, supported by a sling. Multiple professionals were around me. They introduced themselves as ‘the Plastics Team’ and informed me that during surgery the cannula had shifted in my arm to surrounding tissues resulting in my skin changing colour and turning white on my upper arm. I was in so much pain, and I remember telling them “It’s fine” as I was drifting in and out of consciousness. An inner irrational dialogue emerged, worrying I would lose my arm if I told them the truth.

The medical team found no ovarian torsion and removed the ovarian cyst as intended. My belly button area was still in immense pain as I was taken back to the ward after being in recovery. In the ward, I was cycling between feeling hot and cold, then progressively got colder with the chills returning. I could feel my heart strongly beating. The nurses and ward doctors began to poke me, swab me in every crevice, prick me, stick things on me, and squeeze the life out of my arm with the blood-pressure cuff. I had many people in my space in a shared room, separated from the other patients by a curtain. This experience is captured in Figure 4 as I applied Gaussian Blur to create the sense of people being there, but distant from my reality. I felt disorientated but I remember being curious about my fingers and nails and added them as a point of focus on the canvas as they progressively turned bluer. It was only later in my hospital journey that I found out this sign of sepsis was due to my body’s lower oxygen levels.

Figure 4. Susannah Morrison, Blue Fingers and Nails, 2025, digital art.

The Medical Emergency Team call

The ongoing signs of decline post-surgery signalled the beginning of the fight for my life. This was not in a literal sense. I did not have my boxing gloves at the ready to attack, but my immune system did. The body’s overaction in sepsis when responding to an infection is discussed earlier by Arora, et al. (2023). However, to define this in simpler terms, Hammet (2025) states, “Sepsis results in the immune system attacking [emphasis added] healthy organs and tissues” (2025, p.80). Along with my immune system being under attack, my nervous system also felt this. I could not physically or emotionally engage in a typical fight to defend myself, or escape this experience through flight, but I could freeze. I felt powerless as I lay in my hospital bed with no choice but to go limp. This response was biological as we “Freeze (or go limp) when fight or flight is perceived to be impossible” (Kline, 2020, p.25). This choice my body found itself making was not conscious; it was survival.

It was soon after this that the medical staff isolated me to a single room within the ward and called the Medical Emergency Team (MET). The MET consists of medical professionals trained to use their specialised skills with patients whose clinical state is deteriorating and who are at risk of mortality (Dalton et al., 2022). I remember seeing the surgical gynaecologist, anaesthetist, plastics team doctor, and general ward doctor, along with other staff, including the Intensive Care Unit Coordinator, huddling and circling me. Together, the MET team made the call to transfer me to the intensive care unit (ICU) with concerns of intra-abdominal sepsis questioning possible appendicitis.

Intensive care: The white room

In the middle of the night on day two in the hospital, I arrived in the ICU. I was taken to what I remember naming “the white room”. I noticed it contained many lights and was overwhelmingly bright, conveying to me the feeling of being both sterile and clinical. Fear was right with me, along for the ride too, with a sensation of pumping and surging throughout my whole body. I was there to have inserted both an arterial line into my right arm and a central venous catheter in my neck. I was informed by the ICU medical staff that I needed to remain completely still for ten minutes while they inserted the central venous catheter.

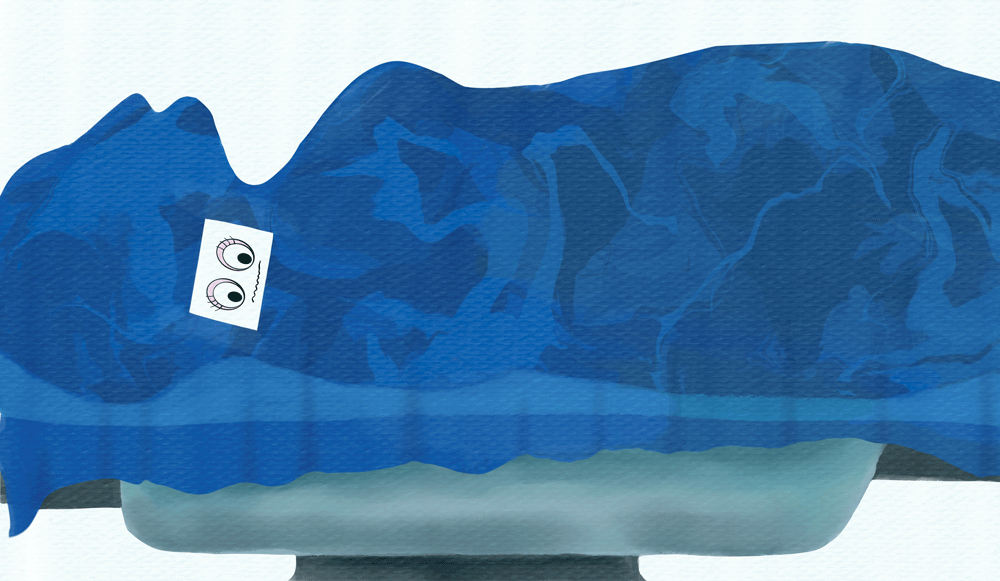

I remember laying on the surgical table in the white room, muscles tensing in an attempt to remain still, and covered by a blue sterile sheet that now felt like it had bonded with my clammy skin like Velcro. My neck was the only part that bore witness to this procedure, so I wanted to illustrate that (Figure 5). The digital art process involved a heavy focus on defining the edges of my body shape to reflect the outward static of being still. To represent the sensation of fear surging throughout my body, I adjusted the layer opacity on the blue sheet to reveal the internal swirl of movement and fear happening beneath. Due to experiencing a decline in my health both physically and mentally, I was cycling in and out of awareness of where I was and what was happening. I felt confused, agitated, and disoriented, which is common amongst people with sepsis (Gyawali, et al., 2019).

Figure 5. Susannah Morrison, Confused and Disorientated, 2025, digital art.

Intensive care: Life-saving treatment

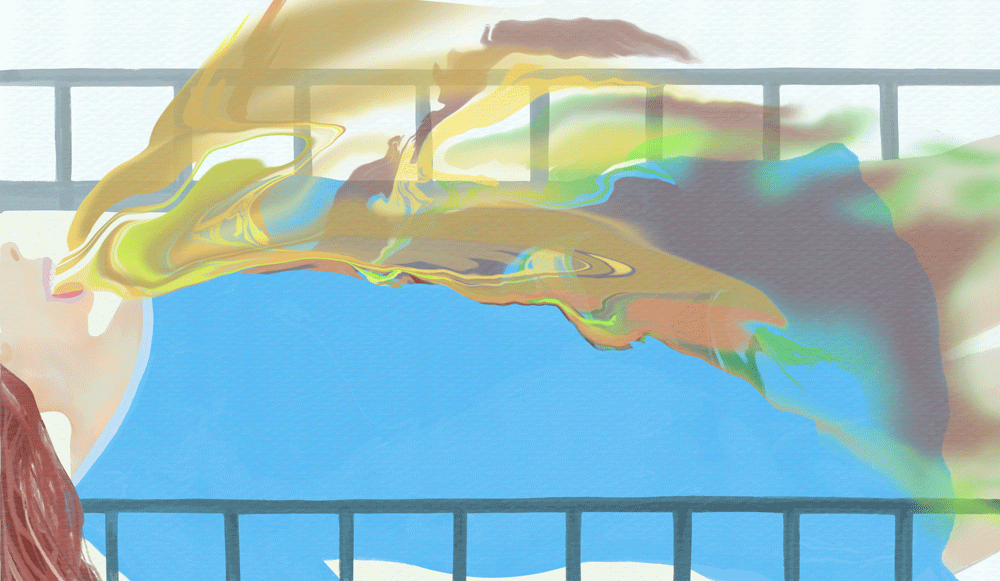

Following the insertion of the central venous catheter and arterial line, I was immediately shifted from the white room to my bed in the ICU, where the medical team administered intravenous antibiotics. Once sepsis has been identified within a patient, time-responsive antibiotic treatment has been found to reduce cases of mortality (Leung et al., 2024). It was still not entirely known by the medical team what the cause of my sepsis was, so they continued to keep me fasted and moved me around the hospital for multiple scans. They did discover that I had experienced bibasal collapse and consolidation, and they treated this with oxygen support. My lower lung lobes had collapsed with fluid building in my pleura, the membrane surrounding my lungs. After three days in hospital, with two of those in the ICU, I continued to receive oxygen support, intravenous antibiotics, fluids, and anti-nausea treatment. I was also on strong pain management. It felt like my whole body was under immense stress, fighting with all its resources. I remember being violently ill from the cocktail of medication pumping through my body. As I turned to my digital canvas (Figure 6) to reconnect with this experience, I was experimenting with colours, shapes, blending modes, and brush opacity between layers. I then used the Liquify tool on the Push setting to create the form as it needed fluidity and force. I found this process allowed me to be in creative flow, which McNiff (2004) speaks of as significant in allowing the art and imagery to communicate. This was very experiential for me, as it was yet unknown which part of the ICU the digital art was speaking to. Through continued inquiry and artful play on my digital canvas, I recognised the fluidity with force in my expression was communicating both the visceral and literal aspects of my experience. This was a very vivid memory for me, as it evoked such a bodily response. I knew then where to place myself within the expression.

Figure 6. Susannah Morrison, Violently Ill, 2025, digital art.

Intensive care: The chair

During the second day of my ICU stay, I was fortunate that a hospital physiotherapist came and encouraged me to sit in the chair. I remember being excited and said, “I see a physio too”. To me, I had found some connection to the world outside of the walls, sounds, noises, and lights of the ICU. Here I was, violently ill, in such shock from what was happening, feeling medically intoxicated, and yet a little glimmer of hope sparked a light in me. This reminded me I had a life beyond what I was experiencing in the ICU. The first few transitions to the chair were the most challenging, as I had so many things attached to me, and I needed to rely on multiple staff to assist.

This chair became a symbol, not just for me, but also for my mum when she visited. This translated to the digital canvas in Figure 7, as I began to reflect on the significance of the chair’s function in my ICU recovery. To see me sitting in the chair gave my mum hope, and to see her hope, in turn, gave me hope. A sense of expansion emerged as I was able to be active in my recovery, finding hope that I could get through this. With critically ill patients in the ICU experiencing uncertainty, hope is highly valued as it has the capacity to motivate and facilitate coping during treatment and recovery (Berntzen et al., 2024). Using the Smudge tool to soften the edges, I used colours and textures to illuminate a dreamscape and contrast the medical environment I had been experiencing.

Figure 7. Susannah Morrison, Hope, 2025, digital art.

Intensive care: Self-awareness

I continued to progress by reclaiming self-care. The ICU nurse braided my matted hair, which had resulted from days in bed without showering: a little gesture that had a huge impact on my self-image. After four days in hospital (three in the ICU), I was brushing my teeth and sitting up on the commode. I was more aware now of how vulnerable and dependent I was, with nurses assisting me with bedding, cleaning, changing body positions, toileting, and getting out of bed. I remember feeling shame in response to this realisation. I had surrendered my whole self and was emotionally numb. My self-awareness was beginning to return, but I still felt powerless. This triggered the re-emergence of my pattern of hyper-independence. Askaree et al. (2025) discuss hyper-independence as a response that occurs in individuals who resist being seen as vulnerable and show an extreme need for autonomy and self-reliance as a coping strategy. I wanted out. I wanted to go home.

I took this experience of my self-awareness returning to the digital canvas seen in Figure 8, beginning with the access point of ‘emotionally numb’. I was drawn to illustrating this hyper-independence and extreme need for autonomy. Some of this hyper-independence was maladaptive, including refusing strong pain management to ‘feel’ in my body, hence the glass shattering being both an element of harm, and of a breakthrough. The juxtaposed contrast beyond the glass began more fluidly with the Liquify tool; a cave emerged. This drive I had to ‘feel’ despite not knowing what followed reminds me now of Leonardo da Vinci’s words (as cited in Isaacson, 2017), “There arose in me two contrary emotions, fear and desire – fear of the threatening dark cave, desire to see whether there were any marvellous things within” (p.20). Through inquiry, I came to know that this desire I felt to feel then was a call to be home, home within myself.

Figure 8. Susannah Morrison, Autonomy, 2025, digital art.

Goodbye: Hospital and sepsis

On the evening of my fourth day in hospital, I had stopped fasting and was able to return to the general hospital ward. The pain in my belly button had now settled with scans showing no signs of appendicitis. The original suspicion of intra-abdominal sepsis shifted to the possible cause of sepsis being from pneumonia as the doctors began to take into account more of my history which was noted in my discharge summary (Hospital, personal communication, 24 December 2024).

I had been feeling unwell a few days before going to hospital and presented in emergency with changes in my body temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate with progression after surgery to changes in my breathing. The signs were present prior to surgery and the general malaise in the few days leading up to the emergency department visit. As sepsis did not result from being in hospital, it is referred to as being community acquired (Liddy et al., 2025). The medical team treated my pneumonia with further antibiotics, breathing exercises with a spirometer, and reduced oxygen support so my lungs could rebuild their function. I was able to eat but had very little appetite. My mouth was very dry from fasting for four days and I had begun to develop oral thrush. The will I had to fight was now replaced with a sense of detachment from reality. I was processing what my new reality was now after transitioning out of the ICU.

My circadian rhythm was out of sync and I was trying to recalibrate. It felt like such a daze. However, I do remember the dancing trees swaying in the breeze in the window. I wanted to recreate this moment (Figure 9), beginning with a photo I captured from my hospital room. Although the photo was factually accurate, my perspective of reality was distorted, and the trees shifted from being in the background to the foreground. The trees were majestic and slowly swayed in the wind, performing a graceful dance that felt surreal, just for me. I stared in awe for hours on day six, my last day in the hospital before saying goodbye and returning home.

Figure 9. Susannah Morrison, Detached Reality, 2025, digital art.

Hello: Home and post-sepsis syndrome

I had now survived sepsis. You would assume this was the end but it was only the beginning of my experience of post-sepsis syndrome. I could barely eat for weeks, spent most of my time on the couch for the better half of three months, and my health declined. I found it challenging to cook, sleep, exercise, think, read, drive, or be intimate with my partner. I was also grieving; my body could not do what it normally could. It was malfunctioning. I would try to say one thing, and another thing would come out. The fatigue was debilitating. I continued to feel like I was in a daze. In some ways, I find it interesting that my breaking through the glass seen in Figure 8, led me straight into another dark place – my recovery. Challenges in sepsis recovery are not a unique experience. This correlates with research by Apitzsch et al. (2021) on the common threads amongst sepsis survivors in recovery being both psychological and physical. These include, but are not limited to, fatigue, exhaustion, cognitive and memory differences, pain, sleeping difficulties, depression and anxiety, particularly as sepsis is life threatening. Furthermore, Apitzsch et al. assert that for most survivors, the initial gratitude for not dying is replaced with the aftermath of processing not just the experience, but a new reality.

My new reality had started. I had left the hospital ready for my recovery. Unfortunately, I did not receive my discharge summary when I left, and this was still not done by my post operative appointment six weeks later. To navigate this new reality, I visited my general practitioner who was as supportive as they could be in the circumstances. However, they also did not have the discharge report, and therefore it was hard to decide what post-care support was needed. Research by Smith-Turchyn et al. (2025) found there was the minimal support for rehabilitation available for sepsis survivors during recovery to adjust to the changes in physical and emotional needs. Moreover, one sepsis survivor quoted in Smith-Turchyn (2025) states that there are limited lived-experience peer networks existed, identifying a need for “Companionship as kind of a therapy program because a lot of people don’t understand what somebody has gone through” (p.6).

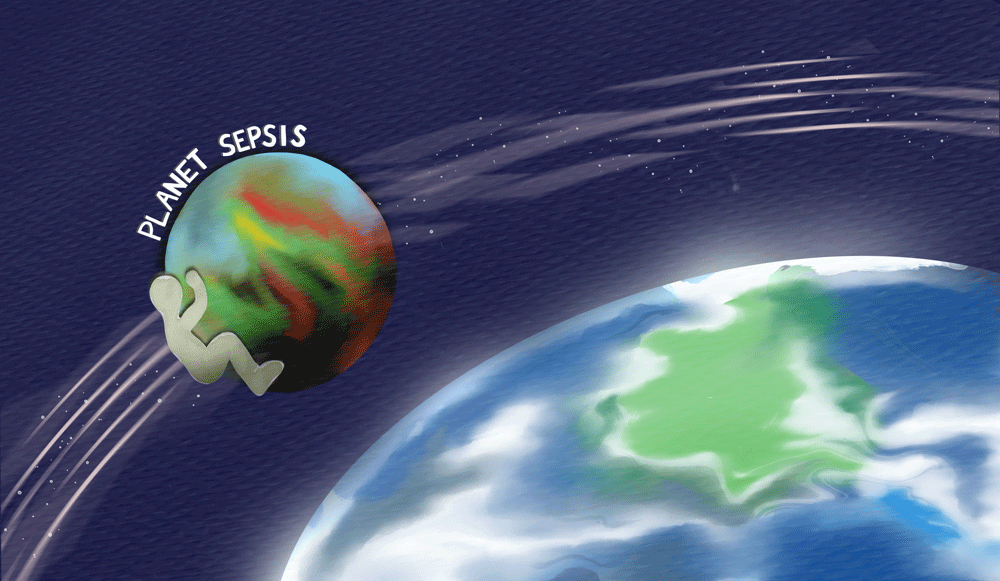

I really struggled with navigating my recovery and this new reality post-sepsis, particularly not knowing if what I was experiencing was typical. I did not know who I was after sepsis, or how to care for myself, besides what I found on the internet. I remember reaching out to an online forum to discuss how I felt like an alien; disassociated and feeling like this body I inhabited was not mine. I revisited the experience on the digital canvas seen in Figure 10. Initially I wanted to illustrate myself as an alien, foreign to the land. This shifted as I began the artistic process creating two planets, one orbiting the other. This experience of sepsis had left me so depleted, physically and mentally, that I felt like I was on another planet, Planet Sepsis. I would frequently orbit Earth on Planet Sepsis when I was disassociated during recovery. This feeling was further exacerbated as I was also processing and dealing with multiple flashbacks of the experience while trying to piece together the aspects of my story.

Figure 10. Susannah Morrison, Disassociated in Recovery, 2025, digital art.

The path forward

Through this arts-based autoethnographic research with digital art, I have found a pathway to process my experience of sepsis, reconnect with my body, and document my journey back to self. It was through engaging in this research that I discovered this article was shaping around two key factors. The first factor was building awareness by sharing the signs of sepsis during its critical phase and through recovery. Research by van der Slikke et al. (2023) asserts that recognising the early signs of sepsis and responding with timely treatment continues to be very poor at a global level. Moreover, these authors argue in their research that sepsis survivors reported a lower quality of life and felt inadequately supported during recovery. When I first presented at the hospital, I did not ask the doctors if it could be sepsis, because I was not aware of what the signs of sepsis were before I began this research. This research also allowed space to explore my challenges with post-sepsis syndrome, and how my own barriers to recovery were common findings amongst fellow sepsis survivors.

The second factor was illustrating the therapeutic potential of digital art as a form of creative expression. This was where I began, with the digital art. I was still struggling with post-sepsis syndrome and stringing together sentences that made sense. I had so much to say but could not find the words to say it. All these memories were carried by my body, still struggling, and battling through the recovery. Each digital expression carried and held me through the rollercoaster of emotions that emerged with this research and supported my body to be present.

I could not use traditional forms of the arts as my energy levels were so depleted, but I still needed creative expression. We now live in a digitally driven world, thus using digital art as a modality within arts therapy settings can offer accessible options to express and create (Malchiodi, 2018). These personal memories of mine needed a voice to heal, which came in the form of my digital canvases. Through this process, I regained my strength and the words followed, beginning my healing journey after surviving sepsis.

This article was written five months after I had sepsis. I will always wonder if the ambulance had come in response to my first request, would they have known the early signs of sepsis and offered another perspective? Could treating the early signs of sepsis prior to surgery have prevented an ICU stay? Would exploring other suspected diagnoses, other than ovarian torsion, prevented the outcome? How would I cope if I developed permanent damage in my arm from the cannula shifting? Will I survive if I get sepsis again? I do not know these answers to these questions, but I do know that the medical team saved my life. I am alive, and with every day I notice more glimmers of myself returning to better health in my PSS recovery.

Conclusion

This article has explored, with arts-based autoethnographic research, my lived experience of sepsis from the critical phase to recovery with post-sepsis syndrome. The research found creating with digital art offered therapeutic benefits in helping me to process and understand the personal experience of having sepsis. In addition, this article highlights that the signs of sepsis need greater global awareness, and that recovery post-sepsis continues to impact sepsis survivors with a lower quality of life, and identifies a need for adequate support during recovery. This article recommends further exploration through arts-based research into how sepsis survivors and/or individuals experiencing health concerns can integrate digital art tools within the arts therapy field to create greater accessibility, broaden the scope of clients, and experience the benefits that digital art offers as a therapeutic modality for creative expression.

Thank you for being with me during my story.

Acknowledgements

I want to acknowledge:

The many people who have died from sepsis. My heart is with their families and communities as they grieve their loved ones.

The medical and research teams who are continuing to review practices and seek ways to act more quickly to save lives and prevent further harm.

The fellow survivors who shared their stories through both Sepsis Australia and Sepsis Alliance in the Faces of Sepsis campaigns as part of World Sepsis Day and Sepsis Survivor Week. These were such a source of strength, grief, courage, and gratitude as I began to recount my own story of sepsis.

References

Abram, D. (2010). Becoming animal: An earthly cosmology. Random House.

Apitzsch, S., Larsson, L., Larsson, A.K., & Linder, A. (2021). The physical and mental impact of surviving sepsis: A qualitative study of experiences and perceptions among a Swedish sample. Archives of Public Health, 79(1), Article 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00585-5

Arora, J., Mendelson, A.A., & Fox-Robichaud, A. (2023). Sepsis: network pathophysiology and implications for early diagnosis. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 324(5), R613–R624. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00003.2023

Askaree, L., Safdar, K., Fraooqui, J., Umar, H., Panhwar, R.J., & Baloch, L.K. (2025). Investigating the relationship between childhood trauma and hyper-independence among university students: From adversity to self-reliance. Research Journal of Psychology, 3(2), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.59075/rjs.v3i2.129

Bridwell, E., Koyfman, A., & Long, B. (2022). High risk and low prevalence diseases: Ovarian torsion. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 56, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.046

Biggs, A.T., & Littlejohn, L.F. (2022). Vaccination and natural immunity: Advantages and risks as a matter of public health policy. Lancet Regional Health – Americas, 8, 100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100242

Berntzen, H., Rustøen, T., & Kynø, M. (2024). “Hope at a crossroads” – experiences of hope in intensive care patients: A qualitative study. Australian Critical Care, 37(1), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2023.07.037

Boyd, C., & Barry, K. (2024). Arts-based research and the performative paradigm. Methods in Psychology, 10, 100143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2024.100143

Caldwell, C., & Bennet Leighton, L. (Eds.). (2018). Oppression and the body: Roots, resistance, and resolutions. North Atlantic Books.

Dalton, N.S., Kippen, R.J., Leach, M.J., Knott, C.I., Doherty, Z.B., Downie, J.M., & Fletcher, J.A. (2022). Long term survival following a medical emergency team call at an Australian Regional Hospital. Critical Care and Resuscitation, 24(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.51893/2022.2.oa6

Dobson, G.P., Letson, H.L., & Morris, J.L. (2024). Revolution in sepsis: A symptoms-based to a systems-based approach? Journal of Biomedical Science, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-024-01043-4

Ellis, C. Adams, T.E., & Bochner, A.P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Article 10. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108.

Gyawali, B., Ramakrishna, K., & Dhamoon, A.S. (2019). Sepsis: The evolution in definition, pathophysiology, and management. SAGE Open Medicine, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312119835043

Hammett, E. (2025). Sepsis: A complete guide. BDJ Team, 12(2), 80–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-025-2890-5

Isaacson, W. (2017). Leonardo da Vinci. Simon and Schuster.

Kline, M. (2020). Brain-changing strategies to trauma-proof our schools: A heart-centered movement for wiring well-being. North Atlantic Books.

Leung, L.Y., Huang, H.-L., Hung, K.K., Leung, C.Y., Lam, C.C., Lo, R.S., Yeung, C.Y., Tsoi, P.J., Lai, M., Brabrand, M., Walline, J.H., & Graham, C.A. (2024). Door-to-antibiotic time and mortality in patients with sepsis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 129, 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2024.06.015

Leviner, S. (2021). Post-sepsis syndrome. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 44(2), 182–186. https://doi.org/10.1097/cnq.0000000000000352

Liddy, E.M., Amin, D.K., McKeown, D.J., O'Dwyer, M.J., & Vellinga, A. (2025). Epidemiology of community-acquired versus hospital-acquired sepsis in acute hospitals in Ireland, 2016-2022. Critical care explorations, 7(7). https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000001289

Madigan, D.J., Kim, L.E., & Glandorf, H.L. (2023). Interventions to reduce burnout in students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39, 931–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00731-3

Malchiodi, C. (Ed.). (2018). The handbook of art therapy and digital technology. Jessica Kingsley.

McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Shambala.

Olander, A., Andersson, H., Sundler, A.J., Hagiwara, M.A., & Bremer, A. (2023). The onset of sepsis as experienced by patients and family members: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(19–20), 7402–7411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16785

Smith-Turchyn, J., Alborzi, M., Hong, J., Hvizd, J.L., McKenney, S., Newman, A.N.L., Rochwerg, B., & Kho, M.E. (2025). Rehabilitation needs, preferences, barriers, and facilitators of individuals with sepsis: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 8, 100339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2025.100339

Taniguchi, T., Tsuha, S., Takayama, Y., & Shiiki, S. (2013). Shaking chills and high body temperature predict bacteremia especially among elderly patients. SpringerPlus, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-624

van der Slikke, E.C., Beumeler, L.F., Holmqvist, M., Linder, A., Mankowski, R.T., & Bouma, H.R. (2023). Understanding post-sepsis syndrome: How can clinicians help? Infection and Drug Resistance, 16, 6493–6511. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s390947

Van Dissel, J.T., Numan, S.C., & Van’t Wout, J.W. (2005). Chills in ‘early sepsis’: Good for you? Journal of Internal Medicine, 257(5), 469–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01498.x

World Health Organization. (2020). Global report on the epidemiology and burden of sepsis: Current evidence, identifying gaps and future directions. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/334216/9789240010789-eng.pdf

Zubala, A., Kennell, N., & Hackett, S. (2021). Art therapy in the digital world: An integrative review of current practice and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600070

Author

Susannah Morrison

MTAP, MIncEd, GradCertDisSt, BTeach, DipCreatArtsHlth

Susannah is a registered creative arts therapist and disability educator based in Kaurna Country in Southern Adelaide, South Australia. She is passionate about the therapeutic arts, and the possibilities they offer in being a catalyst for knowledge, acceptance, change and healing. Susannah is drawn to the field of arts-based research and inquiry as a way to understand relating intersectional identities, and the impact these have on equity and inclusion. Susannah offers individual and group therapy to children and adults within their business, Nourish with Arts. They specialise in neurodivergence, LGBTQIA+, disability, carer support, burnout recovery, and chronic health needs.