Open Access

Published: December 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.2

Word count: 7,572

About the author

Cite this articleko, c. (2025). Comics for re-storying self: Revisiting autoethnographic research from student placement. JoCAT, 20(2). https://www.jocat-online.org/a-25-ko

Recipient of the ANZACATA-JoCAT Author Support Bursary

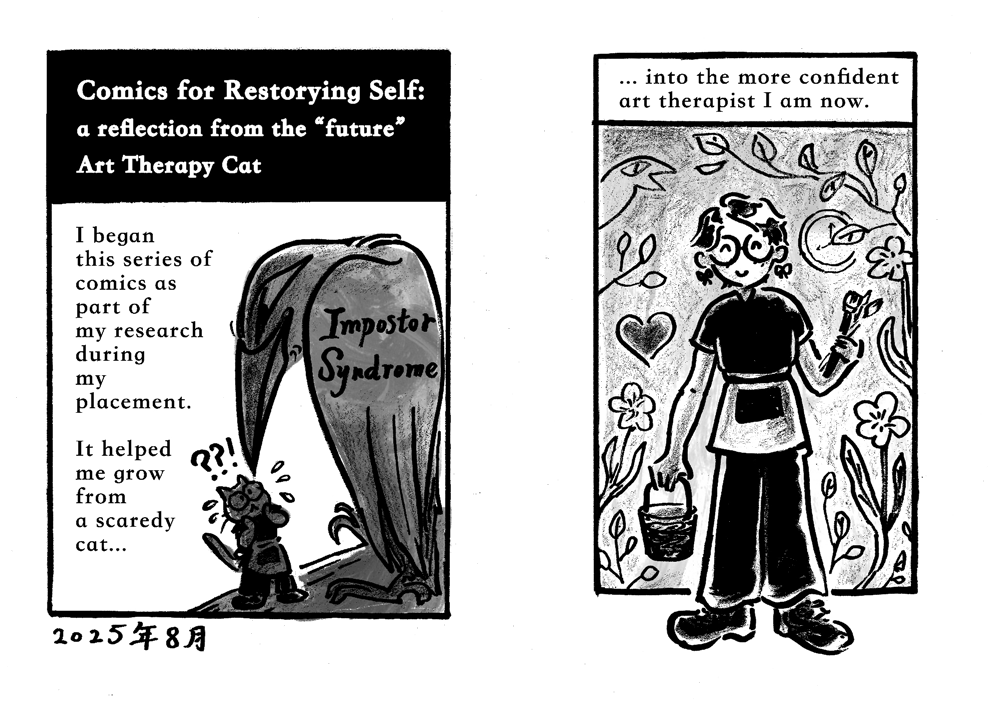

Comics for re-storying self: Revisiting autoethnographic research from student placement

cat ko

Author’s note

There are various storylines unfolding concurrently in this paper. As the reader, you can choose your own way and order of reading. This includes skipping past the research text to read the comic pages on their own!

Abstract

To investigate the therapeutic potentials of creating comics for the development of my trainee art therapist self, I began this critical autoethnography and comics-based research. During the data collection sessions, I created a series of reflective comics about my student placement experiences, then wrote about the process in my reflective journal. Making comics not only improved my psychological state, but I also came away with a stronger artist self and art therapist self. These specific advantages to comics-making have potential to benefit other mental health practitioners, especially other art therapy students on placement, who are also in the process of becoming.

Keywords

Comics, art therapy trainee, professional identity, re-storying, transitional objects, student placement, narrative therapy

Listen to the podcast

Introduction

This paper began as a research project during my student placement, which spanned the last five months of my master’s training to become a registered art therapist. After graduation, I revisited this research with further insights into understanding how this research could be understood and practised by arts therapy professionals.

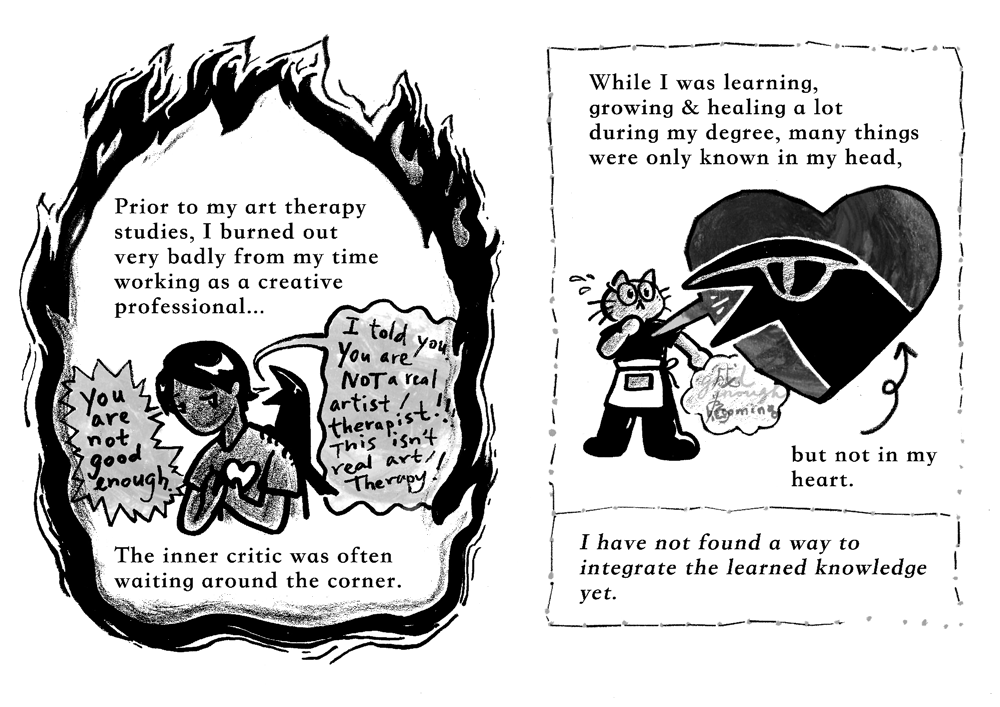

At the beginning of my master’s, I was working through burnout from my previous work in the field of animation. The burnout changed my relationship to my own creative practices drastically. I had difficulty creating and enjoying stories, comics, and animation – the artforms that had once brought me immense delight and had helped me move through challenging times in my formative years. While I began healing my relationship with art-making during my training, there was still an inner, judgemental voice that occasionally resurfaced when I created: “This is not real art. You are not good enough.”

Comics as medicine

My interest in comics as medicine began at the end of 2023, when I began making private diary comics to help me process losing a close friendship. The slow, painful loss of this friend had occupied most of my mind throughout the year, so I was compelled to record pivotal moments that led to our eventual fall-out. As my week of comics-making progressed, I also felt called to illustrate joyful memories with other loved ones (Figures 9 and 10). This process shifted my perspective: I now saw 2023 as a year full of meaningful connections with friends and family, hopeful opportunities and new experiences that helped me grow. In retrospect, I realised I had engaged in a narrative therapy technique of “telling and retelling” (White & Epston, 1990), transforming my story from one of grief into one of joy.

Figure 9. cat ko, another life is possible, 2023, pen and ink, 148 × 105mm.

Figure 10. cat ko, AAAAAA, 2023, pen and ink, 105 × 148mm.

Comics-making encourages multimodal expression through text, image, time and space, making comics a potent artform for expressing life experiences (McCloud, 1993). The stylisation employed in comics creates a space that is less confronting when heavier topics are explored (Lucas-Falk & Hyland-Moon, 2010). Because of these qualities, comics have been embraced by people with lived experiences, clinicians, and researchers to convey content related to health and medical conditions – a genre of comics coined as “graphic medicine” by Ian Williams (Bell, 2022; Graphic Medicine, 2024). Autographic comics can also function as auto-therapy (Venkatesan & Peter, 2018), helping cartoonists resolve psychological conflicts, expand self-perception, explore gender identity, and process trauma and grief (Hasselmo et al., 2023; Heifler, 2022; Lucas-Falk & Hyland-Moon, 2010). These qualities sparked my curiosity about whether a dose of graphic medicine could improve my own well-being during student placement.

Placement beginnings

My practicum training began at a lower North Shore public high school on Dharug Country (Sydney), where I designed a pilot art therapy program to support students’ well-being needs. The high school students came from diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Recurring themes and therapeutic goals for our sessions often had to do with anxiety and stress that surfaced due to academic and social experiences. In therapy, students would speak of a lack of support in their lives and in school. Identity was a recurring theme for this client population, appropriate to their developmental stage as adolescents – a significant stage for the individuation process and exploring who they are beyond their families of origin (Erikson, 1994). Interestingly, this search for self and identity became a noticeable parallel with my journey as an art therapy trainee on placement.

The high school provided strong practical support: a private room for art therapy sessions, a budget for art materials, and freedom with building the program. I received regular onsite supervision at the high school, and weekly group supervision sessions with my university supervisor. During group supervision, I made art with fellow art therapy students and attended to pertinent arisings from practicum. Unlike my personal comics, my supervision art-making had more sensory and affectual qualities – between yarn and paint and crafty materials, recurring visuals of flora, pensive figures, and birds emerged (Figure 11). Although my supervision art-making helped contain surfacing emotions, significant psychological content remained to be sorted through. While supervision helped me reflect on placement challenges, doubt and insecurities lingered.

Figure 11. cat ko, making precious, 2024, acrylics, 105 × 148mm.

During my master’s, I encountered the concepts of “self-compassion” (Neff, 2003) and “art therapist becoming” (Rubin, 2016), which gave me permission to be imperfect as a trainee. Neff (2003) describes self-compassion as responding to one’s own suffering with kindness, through recognising that our struggles and imperfections are part of a shared human experience, while holding challenging emotions with mindful awareness rather than harsh self-judgement. Rubin (2016) writes about becoming an art therapist as an ongoing developmental process. We do not arrive at a fixed professional identity as fully formed therapists; instead, we are always in a state of continuously becoming (Rubin, 2016). Nevertheless, my inner critic often stood defiantly against these ideas, like a bird diligently eating the seeds before they could take root. When sharing my work with fellow art therapy trainees, an inner voice would judge me: “This is not real therapy. You are not good enough”.

I moved from Hong Kong to Australia in 2023 to pursue my master’s, which highlighted significant feelings of unfamiliarity with the local culture and the education system in New South Wales. I often felt alone and confused as the sole representative of art therapy at placement. At this stage, stress manifested in me as disrupted sleep, and my need for a better self-care routine became apparent. Here, my artist self began to wonder: “Could making comics about my placement support my well-being and professional growth as an art therapy trainee?”

Literature review

Student placement challenges

Student placement is a vital part of the accreditation process of art therapy training (ANZACATA, 2024). Unfortunately, placements do not always provide a sufficient structure where students are supported in integrating their theoretical knowledge and constructing their professional identities (Feen-Calligan, 2005; 2012). Students sometimes find themselves as the only art therapy representative at placement, with no other on-site colleagues who are art therapists (Feen-Calligan, 2005). As part of the helping professions, art therapy students are exposed to indirect trauma and at risk of vicarious trauma when working with clients with trauma (Howarth, 2021; Skovholt et al., 2001, as cited in Ortner, 2024). Due to the various challenges encountered during practicum training, many art therapy students are at risk of burning out (Jue & Kim, 2023).

Vicarious trauma, vicarious growth, and resilience

Many in the helping professions (nurses, social workers and counsellors) are required to empathetically engage with people experiencing trauma at work, making them vulnerable to vicarious traumatisation (Kim et al., 2022; Short & Costello, 2022). Vicarious trauma for therapists happens when they internalise the trauma narrative of others at work, which increases their chances of developing adverse physical, emotional, and relational symptoms, and can affect their ability to work (Kang & Yang, 2022; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995). Without adequate care, this may lead to compassion fatigue and burnout (Figley, 1995; Kim et al., 2022; Knight, 2013). However, it is important to acknowledge vicarious growth and resilience in those impacted by secondary trauma: just as those who have experienced trauma are capable of post-traumatic growth and becoming more resilient (Van Der Kolk, 2014, as cited in Oostdijk, 2018), so too are those who have experienced secondary trauma (Kang & Yang, 2022).

Creative interventions for indirect trauma

Creative interventions are shown to have positive effects on helping professionals experiencing vicarious trauma, psychosocial distress, and burnout: studies show that arts-therapy based interventions assist healthcare workers in increasing resilience, as well as fostering more positive relational ties and more positive emotions (Kim et al., 2022; Tjasink et al., 2023). Over the years, art therapists have begun exploring different creative practices for self-care and processing vicarious trauma, such as visual journaling (Gibson, 2018), storybook-making (Hopkins & Goss, 2013) and response art (Short & Costello, 2022). Art therapy student Dayna Ortner (2024) has also explored applying various forms of the creative arts (visual art, creative writing, and dance) for self-care during student placement.

Making comics for well-being

In recent years, there has been an increasing amount of academic literature investigating the healing potential of making comics. In a study, Phang (2023) explored the therapeutic benefits of comics-making and compared the medium with non-sequential art-making by inviting research participants to create single images and comic strips. Phang (2023) suggested that comics are an ideal medium for synthesising narrative therapy and art therapy to allow for re-storying alternative self-stories. Other art therapists have pointed out the potential of comics for therapeutic containment within the comic panels (Duff, 2024; Gysin, 2020; Hagert, 2017). The act of laying down self-stories frame by frame to form narrative comics also assists the process of creatively externalising life problems in a therapeutic way (Mulholland, 2004; Venkatesan & Peter, 2018; Williams, 2011). In autobiographical comics where lived experiences are shared, the relationship between comic artists and their readers can bring out the positive benefits of being witnessed in a healing way (Bell, 2022; Khan, 2021). Synthesising art therapy approaches, comics theory, and narrative thinking, Bell (2024) proposed an art therapy model named “The Portal and the Path” to foster resilience through creating autobiographical comics. Nevertheless, Bell (2024) noted that there is a scarcity in art therapy literature and practice examining the healing potential of comics, especially in comparison to the growing number of voices in the field of Comics Studies.

As of the time of writing this paper, there is only one study on the application of comics-making for the purpose of self-care and facilitating professional growth amongst helping professions. In a limited study of the benefits of drawing comics to combat clinical burnout by Maatman et al. (2020), medical students and residents were invited to capture their challenges during clinical practice. The paper concluded that comics could offer a space for expressing stressful experiences and increase emotional awareness. However, further studies on the benefits of this practice on the well-being of allied health students during practicum training is required.

Research design

This research is a synthesis of comics-based research (Kuttner et al., 2018) and critical autoethnography (Jones & Harris, 2021), and adopts thematic inquiry for my data analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The research is autoethnographic, with myself as the sole research participant. In addition, all confidential client information has been omitted from my comic artworks.

Comics-based research is an emerging type of arts-based inquiry, where comics are used in the process of data generation and analysis, or to represent collected data (Kuttner et al., 2018). To investigate the therapeutic benefits of creating comics, the research data was collected through my immersion in the comics-making process in four biweekly sessions. Additional consideration was given to the specificities of the art form (such as the usage of space and framing within the comics) during the data analysis phase.

Critical autoethnography entails studying and critiquing culture through studying and critiquing the self, in order to investigate how our experiences are constructed by systems of oppression, privilege, and power within these social contexts (Jones & Harris, 2021). Using autoethnography through a critical theory lens, I have reflexively examined the culture of comics and self-care within the context of my personal art therapy student placement journey to gain further understanding of ways that underlying structural power relations influence and shape my experience. This framework encouraged reflection through comics-making as a self-care practice for professionals and clients within the wider context of the helping professions.

Data collection

Four sessions of comics-making as journaling were planned to evaluate my well-being on placement. These sessions were structured as 60–120 minutes of comics-making and 30 minutes of reflective writing.[1]

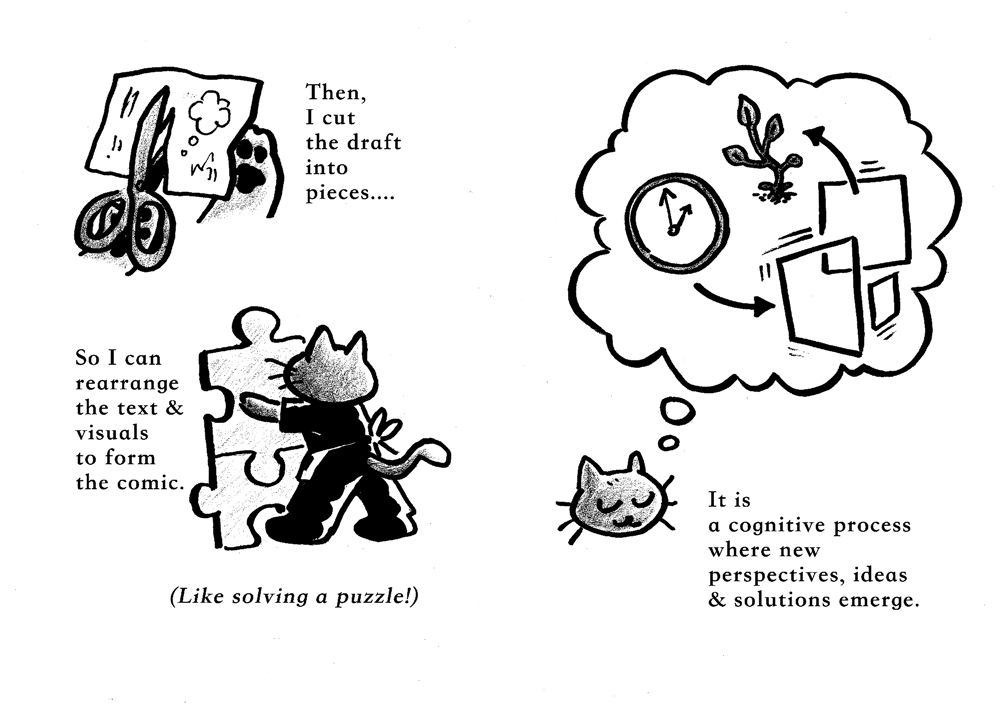

The process of comics-making for these sessions was close to my personal comics-making practice to ensure a steady creative environment during data collection. This entailed three phases:

a beginning ideation phase, where I scribbled initial thoughts on scrap paper;

a drafting phase, where I rearranged these elements to form the basis of a comic; and lastly,

creating the final comic by inking the lines on paper with black markers.

My aim for comics-making was to reflect on my feelings and experiences during placement, which was further guided by a list of optional prompts that I designed based on two existing studies into comics-making as therapy (Duff, 2024; Khan, 2021):

Use comics to capture your feelings today.

Draw a moment when you are disappointed with your placement performance, then draw your ideal “therapist self”.

Write a 7-sentence conflict story related to your placement incorporating the following: “At the beginning… And it was… But then… And so it became… And then… And I… Finally…” Create a comic based on this.

After a “body scan” meditation, create one panel picturing yourself. Draw a speech bubble capturing the message(s) your body revealed during meditation. Leaving room for plenty of gutter space, draw several panels illustrating the message(s). Then fill the gutters with what was not expressed.

Data analysis

After the collected data (comics and reflective writing) was collated, it was scanned for keywords and key phrases, then sorted into themes through a cyclic process of thematic analysis to excavate main themes that responded to the research question (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The themes were then reflexively examined using a final art-making session, using comics to critically reflect upon the data.

Data gathering

Session 1

Figure 12. cat ko, Session 1, 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

The first comic (Figure 12) answered the prompt: “Draw a moment when you are disappointed with your placement performance, then draw your ideal ‘therapist self’”. This reconnected me with a story from The Dynamics of Art and Therapy with Adolescents by Moon (1998), and the importance of being patient with my clients, and with myself.

Session 2

Figure 13. cat ko, Session 2, 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

I entered the second session with strong feelings about a common occurrence at placement, and I followed a prompt to “capture [my] feelings [from] today”. This comic (Figure 13) mirrored anxieties about the future as my placement was coming to an end. I noticed the tension between the expectations I felt from the school and the reality of being a student on placement; I disliked my situation. The day after this session, I requested a meeting with the school about returning next year as a qualified art therapist. This created the change I was seeking: I was offered a potential position!

Session 3

Figure 14. cat ko, Session 3, 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

The third comic (Figure 14) began with a body scan check-in prompt following an overwhelming day where insecurities had surfaced. However, the body scan ‘evolved’ and my ‘magical girl’[2] transformation sequence emerged through my comics-making. Magical girls may struggle and fail despite their magical abilities, but their strength is their ability to grow through the challenges. This session’s comic reminded me to ‘[hold] space for my own growth and gentle becoming’.

Session 4

Figure 15. cat ko, Session 4 (page 1), 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

Figure 16. cat ko, Session 4 (page 2), 2024, pen and ink, 148 × 210mm.

Without following a prompt, my fourth comic (Figures 15 and 16) explored two challenging situations at placement that seemed ‘not connected or related’ at first. However, during the process I discovered a common theme about time: my ‘feel[ing] pressured by the school to help “save time” for my colleagues, the demands of “time” as a trainee art therapist and how people rarely have time for [the students]’ at school. I even felt an urge to expand into an extra page (Figure 16) to create more space, which helped me realise the importance of holding space and keeping time for the students as trainee therapist.

Data analysis: Harvesting themes

Comic as containment

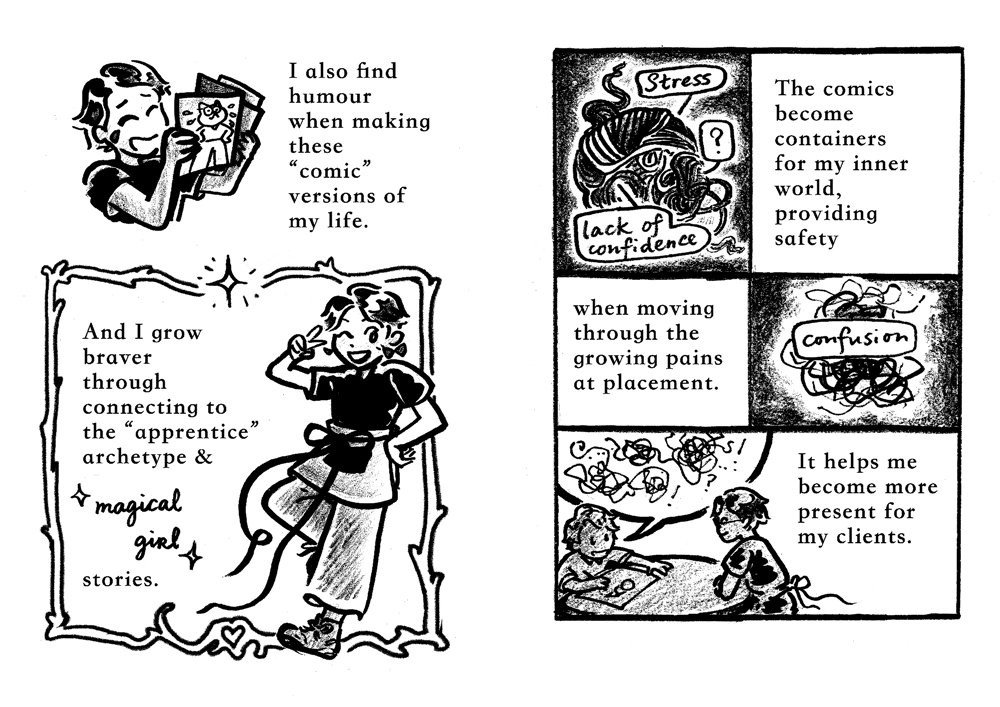

The comics became containers for psychological content before I started processing them on a conscious level. As I inked the lines of the comics to finalise my artworks, I noticed I was ‘externalising my thoughts and feelings’ about the situation. I reported an improvement in mood after each session: I began the sessions feeling ‘anxious’, ‘overwhelmed’, ‘exhausted’, or ‘frustrated’, and became ‘calmer’ and ‘felt lighter’ after ‘having put [the thoughts and feelings] down on paper’.

Reflective space

Every comics-making session felt reflective, and encouraging of cognitive processes. When I created the drafts of my comics, I began by scribbling my ‘initial thoughts surrounding a situation or feeling that stood out to me during my placement week’. Fresh ideas surfaced during this stage, such as ‘how to deal with a tricky situation at hand’, and ‘new perspectives to understand growing therapist self’. Every session involved ‘making sense of’ and ‘creating new ways of seeing’ existing circumstances. They became important check-ins with how I was feeling, and I felt an ‘increased emotional self-awareness’ after these four sessions.

Highlighting the comical

Surprisingly, I found myself adopting a storytelling tone in these comics that is ‘more comical’ than my usual artwork in other mediums. The exaggerated facial expressions and punchlines in the comics ‘brought a sense of humour’ to my experiences. Representing my colleagues and myself as animal characters introduced absurdity and lightness into situations that previously caused frustration for me. My increased awareness of the humorous parts of these experiences brought a positive shift in how I understood my placement.

Archetypes and individuation

A notable archetype of the apprentice surfaced over these four sessions, which merged with the appearance of ‘magical girl genre’ motifs in Sessions 3 and 4. The emergence of this motif was a significant turning point that led to more confidence in my trainee art therapist self. While remembering the stories connected to these archetypes, I became comforted by the universal story of a hero character who keeps trying ‘in the face of challenges and adversity’.

Making the comics helped me become aware of, and connect to, the power behind the apprentice archetype and the narrative of learning. Exploring my placement experience led to ‘more direction’, ‘a sense of grounded-ness’, and ‘increased confidence’ in my trainee art therapist self. The process assisted my creative problem-solving, which resulted in newfound ways of practising art therapy. The sessions cultivated a more ‘gentle’ and ‘compassionate’ self-regard for my ‘growing student self’, who is still on the journey of ‘becoming a good (enough) art therapist’.

Re-storying

Comics-making ‘encouraged a retelling of situations’, and the sessions were ‘healing’ and ‘transformative’. For example, Session 1 turned the disappointment in my performance into a discovery of the need for patience. I realised that the situation was not caused by my inadequacy. Instead, it was an occurrence in the therapeutic process that I need to learn to respond to.

The creative power from the second session even extended beyond my comics and led to direct action at the high school. Creating the comic led to my request for a meeting with the headmaster about possibilities to stay on next year – an action I had been postponing due to my fear of confrontation. However, this comic became a wake-up call that ‘encouraged advocacy and support[ed] action at placement’.

Discussion

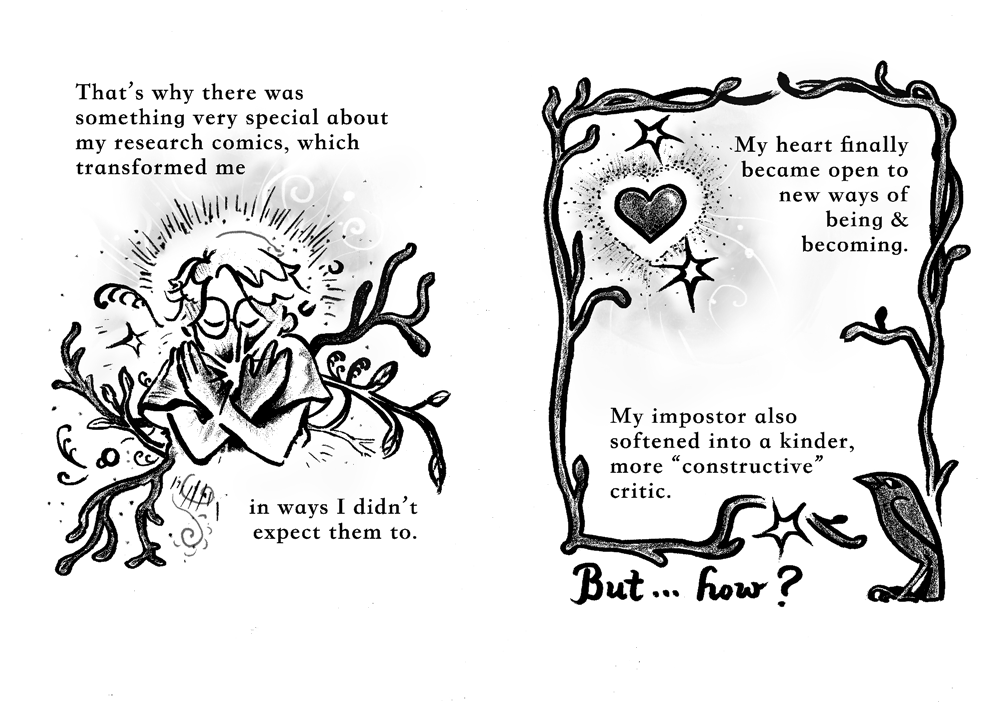

The results of my inquiry show that comics creation can provide a space for synthesising art therapy and narrative therapy techniques, which aligns with existing literature on the therapeutic benefits of comics-making. My research comics created a container to externalise psychological content from the placement experience, to reflect and process the material that was formative to self-stories related to my trainee art therapist self, and in the process, transform my story and my growing artist-therapist self.

Across history, peoples have used storytelling to restore emotional and relational balance (Malchiodi, 2019). Narrative therapy achieves this through identifying, externalising, and deconstructing ‘problem stories’ – dominant problem narratives we have about ourselves and others that influence how we interpret certain situations and experiences in unhelpful ways (White & Epston, 1990). When we challenge these problem stories through identifying other stories, transformation and healing happen. A narrative therapy approach to comics can be adapted to construct a living experiential reality where clients gain insight and create cognitive shifts in their perceptions of their lives (España et al., 2024; Phang, 2023). Narrative art therapy encourages the comic artist to organise and recontextualise their sequential art narratives, and in the process, externalise and deconstruct problems they are facing, and discover their own hidden strengths (Khan, 2021).

Making these autobiographical comics led to the re-storying of my student placement experience as an art-therapist-to-be, growing from an ‘anxious’ art therapy student who was not confident in their abilities and who felt ‘not good enough’, into an art therapy student who was ‘more confident’ and ‘patient with [their] own becoming’. This process was facilitated by affordances unique to the art of comics-making:

The multimodal nature of the medium provided varied ways of self-expression (Lucas-Falk & Hyland-Moon, 2010), and comics (the process of their creation and the final products) offered a container for externalising psychological content onto the comic pages (Duff, 2024; Hagert, 2017; Mulholland, 2004), from which the problem story emerged.

The medium’s encouragement of humorous and cognitive engagement with my experiences helped me re-evaluate internalised self-stories (Duff, 2024; Fernandez & Lina, 2020; Heath, 2000; Khan, 2021).

The archetypes within the comics-making tradition assisted me in considering alternative retellings of my story (Bell, 2022; Mulholland, 2004).

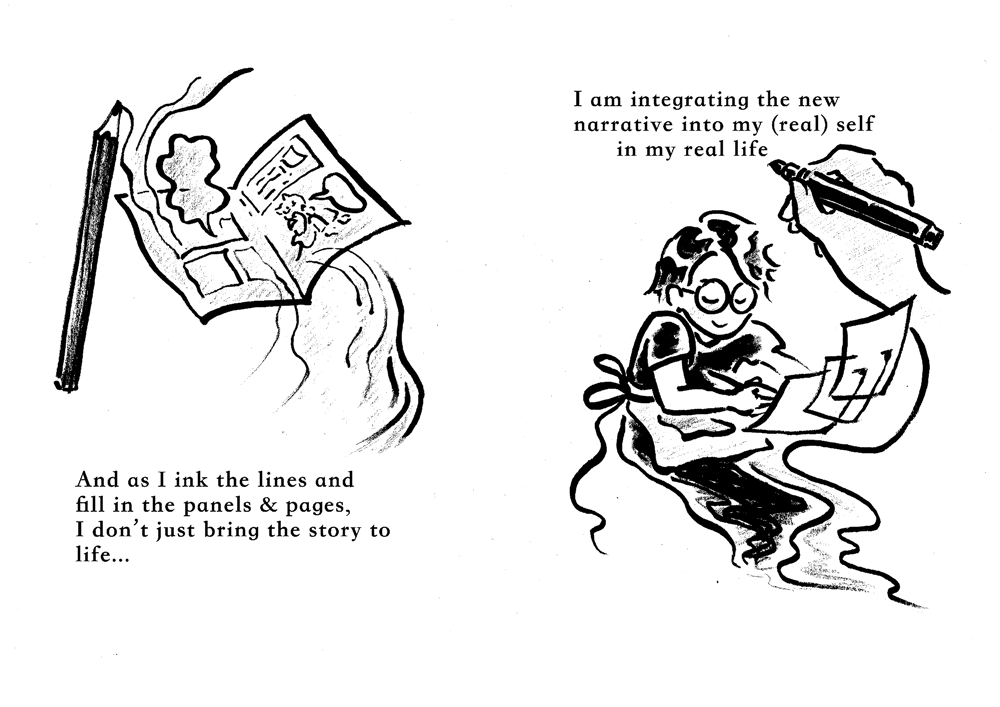

The repetitive and immersive nature of creating my story through comics was useful in integrating new stories into my being (Hinz, 2009).

Together, these properties facilitated the re-storying process unfolding within my research comics – allowing the problem story of not being good enough to be dialogued with and transformed into an emerging story of gentle becoming.

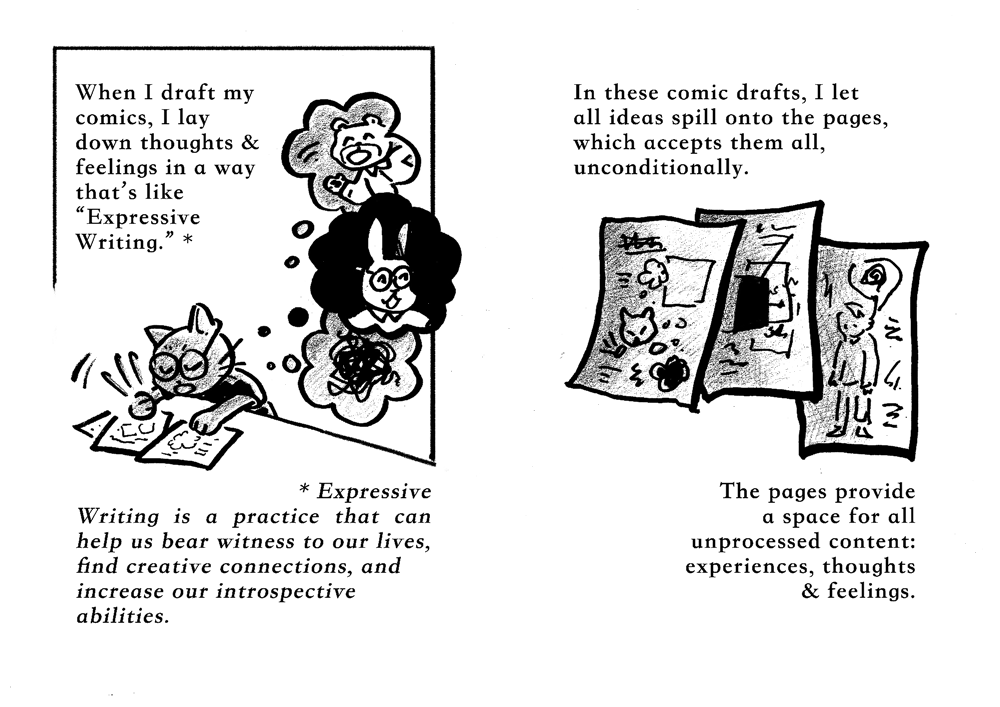

Telling the problem story: ‘I am not good enough’

During the comics-making process, the problem story can be drawn and externalised from the self in visceral and concrete ways. My comics-drafting stage was akin to the practice of expressive writing. This method, developed by Pennebaker, has the potential to help writers bear witness to their experiences of trauma, find creative connections, and increase introspection (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007). The draft comic pages became initial containers for unprocessed internal content: I could lay down all memories, thoughts, and feelings in the safe hands of these non-judgemental pages before processing these experiences. The psychological material was then available as visuals and text on paper, which I arranged and rearranged to form ideas for the final comic.

Art therapists have explored the various ways the drawn border on a page (Riley, 1999) and comics (Hagert, 2017; Mulholland, 2004) can serve as containers for holding our symbolic images, storied lives, and inner psychological experiences. Experimental cartoonist and art therapist Malcy Duff (2024) proposes that the ‘gutters’ (the space between the comic frames) made room for imagination and containment. The gutters in comics provide structure to hold the story, whilst simultaneously offering moments of in-between spaciousness that support arising unconscious material – the untold stories, emotions and responses. As containers of internal content, my comics became a device to confront experiences and emotions in a safe and manageable way.

This medium encouraged externalising personal experiences that I would otherwise feel reluctant to expose, including ‘deeply embarrassing’ moments at placement. The stylisation of reality in comics supported an exploration of heavier topics, because the content felt less confronting when expressed in comic form (McCloud, 1993). The comic strip consists of bordered panels, pictures, and words that combine to construct a narrative sequence – it engages in storytelling as healing through a diverse range of modalities (Lucas-Falk & Hyland-Moon, 2010). The medium comes with a wide set of vocabulary that incorporates text and symbols to denote different emotions. These shortcuts expanded my toolbox for self-expression, helping me depict my reflections surrounding the placement experience. For example, I could express emotions of ‘uncertainty’ and ‘uncontained thoughts and emotions’ through the ‘lack of frames’ and ‘blurring of boundaries’ in the first panel of my third comic (Figure 14), before I had the words to describe how I felt.

From the data, a problem story appeared: my inner critic’s narrative of being ‘not good enough’ as a trainee. It was revealed how often I struggled with my impostor syndrome during my placement, feeling overwhelmed by insecurities and confused about forming my art therapy practice and identity. Externalising the problem story through comics allowed me to separate my clients’ struggles from my own. I considered the possibilities of unhealed wounds from the teenage part of me, and the way I might be vicariously experiencing the peer pressure and judgement amongst my adolescent clients. Therapists can experience vicarious trauma when they internalise the trauma narratives of others, which can negatively impact their well-being (Kang & Yang, 2022). I recognised my feelings as partially a result of vicarious trauma (internalising my clients’ self-stories), and an experience of countertransference where I felt helpless in the face of my clients’ challenges. Understanding my insecurities about the seriousness of my work as a trainee art therapist in a school through the lens of countertransference, I also realised the way my student-clients’ issues in life may often be seen as ‘not serious enough’.

Retelling the story: ‘I just need time to grow’

As an art therapy trainee struggling with impostor syndrome and an artist moving through burnout, I was on a path to heal, to learn, and to re-/build a new identity as artist-therapist. Drawing myself and my experiences into stylised comics had a distancing effect that was optimal for processing and re-storying. During the process, I was encouraged to consider alternative ways to tell the story of my trainee art therapist self.

Practicum training can be challenging for art therapy students (Jue & Kim, 2023), and the use of humour in comics encourages an alternative retelling of experiences that seem especially difficult. My comics’ comedic focus created a playful atmosphere for my life stories. This lighter atmosphere invited my regression and openness to exploration during the art-making, complementing other simultaneous creative processes. Art therapist Wende Heath (2000) created comics about the funny moments in her journey of battling cancer and undergoing operations and radiation. Her comics led to an increased awareness of the humorous moments in an otherwise dreary experience and expanded her readiness for positive events to happen. Like Heath, I began to view my challenges in a more light-hearted way, which shifted my understanding of the placement experience to become more positive, and improved my performance as a trainee art therapist.

The narrative construction stage of making comics encourages comic artists to take a reflective distance from their internal and external states, due to its strong demand for engagement with the cognitive dimension in the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) (Hinz, 2009). The ETC describes the different information that is processed and attained by our nervous systems from our physical self, emotional self, and intellectual self during the creative process. The information is then compiled to generate adequate responses to the situation at hand. Instead of simply re-experiencing feelings and events, the comic artist has to observe the psychological content within their minds and make stylistic and creative choices about how to depict these experiences on paper (McCloud, 1993). Making comics involves constructing sequenced panels and a narrative through drawing, which provides a reflective distance that can be used for restructuring schemas and changing patterns of behaviour (Duff, 2024; Fernandez & Lina, 2020; Khan, 2021). While making the research comics, I could examine my thoughts, feelings, and experiences from afar: “Does this make sense? Is this the only way to understand my story?”

In comics, multiple perspectives and concurrent stories can exist within the same page (McCloud, 1993). For example, in my Session 3 comic, I could juxtapose my anxiety-filled inner dialogue as a trainee with my subsequent response that was filled with hope and self-compassion (Figure 14). Upon reflection, I noticed familiar visitors in the second panel of this comic: the floral and pensive figures from my supervision art (Figure 11) had transformed into my magical girl alter ego (Figure 14), alongside concepts of self-compassion and art therapist becoming. Here, another voice, more compassionate and patient, spoke up in response to my critical voice in the first panel. Within this same comic, I also documented my past self and present self, while drawing my future self into existence, depicting a non-linear unfolding of my various selves and states of being. Through dialoguing with my inner selves and stories in comics, I understood what Rubin (2016) meant when she wrote about art therapists as continuously becoming.

Gysin (2020) links the process of making comics with the narrative therapy approach of retelling. In narrative therapy, performing stories can highlight often-overlooked moments when we defied the dominant problem stories in our lives – these important instances of resourcefulness, resistance, or resilience become starting points from which we can forge new ways to story our lives (White & Epston, 1990). Through the externalised story in my comics, I understood the protective function of my inner judgemental part. I realised the internal critic was trying to keep me safe after the burnout by staying hyper-vigilant: if I performed perfectly, I would not be singled out as ‘not good enough’ and subjected to the shame and distress that previously led to my burnout. My comics allowed alternative voices that contradicted the critic’s fears to surface: “Other students struggle too, experienced therapists work with uncertainties daily, and leaning into the discomfort of unknowing is part of the process of becoming an art therapist. (In the meantime, why not have a good laugh?)” Presented with other perspectives and information, my inner critic softened. Making these comics was an act of transformative performance, where I created conditions for self-kindness and stories of enough-ness to grow in my inner landscape.

Through fostering light-hearted and reflective engagement with my experiences, comics helped me to complicate the world in which the problem story lived and challenge the existence of one singular dominant story. A story of growth and learning to be patient unfolded in the data comics: learning to be patient with the process, with my clients, and with myself. Instead of ‘not [being] good enough’, I ‘just need[ed] time to grow’.

Integration and becoming

Comics-making provides a space for the integration of new self-stories, during which the process of individuation can be supported, allowing for the emergence of self.

In Jungian psychology, individuation is a journey of reconciling with the different aspects of yourself – a path to becoming more you (Mayes, 2020). Comics-making facilitates the process of individuation through connecting the creator with universal archetypes that have been depicted in the medium throughout the history of comics (Bell, 2022). When we consciously relate to archetypal patterns within us, we can tap into the transformative powers of the archetypes and increase understanding of our true self as individuals (Carp, 1998, as cited in Bell, 2022). After creating their comic alter ego, the artist can express themselves through their comic counterparts freely, without the usual confines of real life (Bell, 2024). Using comics, the artist’s self can surface during the creation of a character (Bell, 2022). As he grew up, Mulholland (2004) created comics to make sense of different life problems he was experiencing. In the safety of the comic world, Mulholland explored his own growth through his character’s journey. The character’s storyline became a tangible way to explore conflicts and resolutions in the comic artist’s life, as he grew and became more him (Mulholland, 2004).

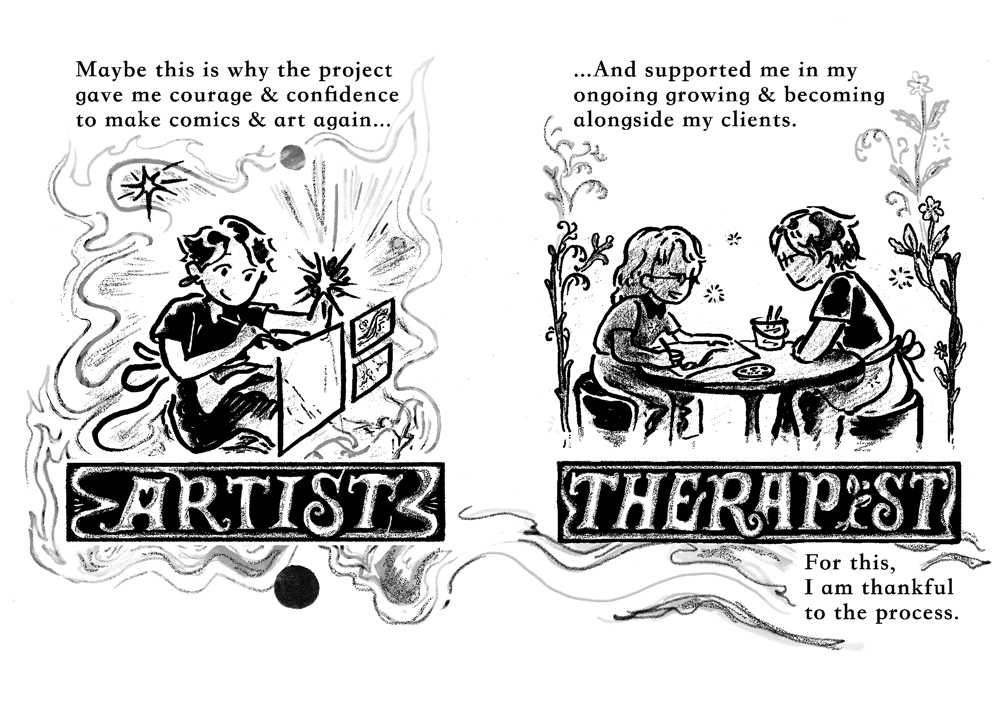

My four sessions of making comics assisted the emergence of my trainee art therapist self. In many stories, the apprentice is an archetypal hero who has to overcome multiple obstacles in their journey to master their craft. Through my student character, I was free to imagine what an ideal art therapist would look like or envision myself as a magical girl with superpowers. This process fostered the formation of my professional identity, led to more kindness and patience towards my trainee art therapist self, and increased insight into how to continue my ongoing becoming. This connection to the apprentice helped me reframe my experiences as ones commonly experienced by art therapy trainees on placement (Jue & Kim, 2023), which lessened my feelings of isolation and emboldened me to ‘change the story’ in real life. In creating these comics, I was working through my own insecurities as an art therapy student and modelling the process of individuation for the student-clients I worked with as well. Here, I consider how my comics helped me connect with my feelings towards the imperfections of the placement system, boosted my confidence in my trainee art therapist self, and fuelled my bravery to negotiate for more post-graduation security. When I realised that this was not only my story, but the story of a wider collective of art therapy students, I became moved to advocate for myself at my placement setting, rewriting the story beyond my comic pages.

Within the comic, I found a space to safely alter the narrative in ways that strengthened my sense of self; I was able to synthesise my external reality and my inner world to enable my becoming, which happens when one is connected to the creative dimension in the ETC (Hinz, 2009). Through making comics, I could revisit challenging experiences safely and freely, rediscover my own sense of agency, and expand my capacity for growth and resilience (Malchiodi, 2021; Oostdijk, 2018). Making comics helped me tap into the creative dimension, which supported my integration of new patterns of information-response generation (Hinz, 2009). When we tap into the creative dimension, we tap into the potential of integration: we strengthen bonds between the information in our nervous systems and the achievement of our goals (Hinz, 2009).

Making the placement comics provided a different experience to me compared to my supervision artwork. The comics stood out due to their long-lasting impacts on my well-being, and I became a much more confident artist and trainee therapist from the experience. The process of creating my final draft of each comic, and the subsequent inking of the drafted comics, became an experience through which new self-stories could be processed, made sense of, and integrated into my own being. This process of reflection and creative problem-solving related to my placement experience continued when I revisited the comics as a reader-researcher. After graduation, I continued finding new ways of understanding these comics and this research through reading and experiencing the stories again.

Completing the comics brought about a sense of accomplishment and improved self-esteem (Lucas-Falk & Hyland-Moon, 2010; Tjasink et al., 2023), which helped me heal from burnout. The finished comics became tangible proof that I could still create stories, and that my planned creative projects could end in satisfaction and accomplishment, rather than depletion and failure. Reclaiming my creative agency through comics helped rebuild confidence in myself as a storyteller and artist, and I practised becoming more compassionate towards myself through the process of creating and reading the comics.

In my internal landscape, my comics created a safe corner for other parts of myself to surface: the compassionate witness, the curious learner, the artist who loved telling stories... These voices challenged my inner critic and diversified the stories that narrate my life. My artist-therapist self emerged from my comics believing that ‘I am good enough. I can provide the art therapy that my clients need. I can make art I am proud of. I am not perfect, but this means that I have time to grow and become more me’.

Through the creation of these research comics, I connected to my trainee art therapist self and growing artist–therapist self through the student archetype and tapping into the creative dimension. This integration of my new story of patience and growth reinforced a gentle self-compassion towards my own artist–therapist becoming.

Comics as transitional objects

As I engaged in a final art-making session responding to my research, one last theme surfaced: comics as transitional objects (Figures 17, 18 and 19). Transitional objects are special items that help children feel secure as they begin to explore the world, keeping them company as they navigate between dependence and independence (Winnicott, 1971). Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott (1971) theorised that, when infants discover and take ownership of a transitional object, they find comfort and develop autonomy during the process of individuation, as they spend increasingly more time away from their primary caretaker. These transitional objects are often the child’s first ‘not-me’ possession, the first object in their lives that they can control and manipulate through the realm of imagination and physical interaction; the objects are also an extension of the child (‘me’), a part of their possession and their identity.

While Winnicott never wrote about the use of comics as transitional objects, he reached out to Peanuts creator Charles Schultz, seeking permission to use Linus and his security blanket to explain his theory of transitional objects (Caldwell et al., 2017). Like Linus’s blanket, my research comics held me through moments of transition and growth, offering continuity and grounding while I navigated uncertain terrains during training.

Figure 17. cat ko, Session 5 (page 1), 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

Figure 18. cat ko, Session 5 (page 2), 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

Figure 19. cat ko, Session 5 (page 3), 2024, pen and ink, 210 × 297mm (spread).

In her autobiographical comic Are You My Mother?, Alison Bechdel (2012) engages with Winnicott’s concept of the transitional object. While examining her complex relationship with her mother, Bechdel also explores whether making her comic can create the holding environment that she did not fully receive from her mother while growing up. Using the transitional space of comics, Bechdel explores what she could not before. In creating Are You My Mother?, she transforms her relationship with her mother into an object (the comic) that she has control over. In the comic, she could relate to her mother in ways that are different to her experiences in real life. Through creating the book, Bechdel could repair her relationship with her mother, and draw herself being held in the ways that she longed to be held by her mother, freeing herself from the feelings of lack when the care from her mother was lacking.

In the same vein, making comics about my placement experience became a means of holding myself through the transitions during practicum training. The lack of sufficient support and infrastructure for trainee art therapists on placement is one of the main causes of psychological burnout (Feen-Calligan, 2005). Jue and Kim (2023) pointed out that major factors leading to burnout in art therapy students during their placement include obstacles in therapeutic progress, the emotional burden of therapeutic work, feeling a lack of respect and understanding from colleagues, and being overworked at their placement settings. Students who are the only art therapy representative in the placement setting also have to reconcile by themselves the conflicting perspectives of their art therapy training against those of colleagues who are not trained art therapists (Feen-Calligan, 2005). While I felt relatively supported at the high school I was placed in, these themes were echoed in both my placement experience and my research comics. For a trainee art therapist, practicum training is a time of traversing between spaces of the known and unknown, between the support of supervisors and professors and the new terrain of art therapy. The comics in this research inquiry became transitional objects that helped me navigate between transitory states where I had to experience therapy practice independently, and a time when I could seek counsel from my supervisors again.

My research comics held the anxieties of my trainee art therapist self that surfaced during student placement. The comics created spaces that were neither fully ‘me’ nor fully ‘not-me’ (Winnicott, 1971): during the process of making comics about these transitions, I became both the self who was experiencing the events, and the self who was observing and shaping the events. As transitional objects, the comics held my trainee art therapist self and allowed for my experiences to be witnessed through my artist self and my future artist-therapist self. As comic artist, I bore witness to my experiences while I laid these feelings and events down on paper. As reader, I bear witness again when I return to read the comics after bringing them to life. Giving form to these stories provided a sense of security that was akin to the way Linus could return to hold his trusted blanket the research comics became proof that these stories existed and could be returned to for safety and comfort.

Duff (2024) proposes the comic panel can be a transitional tool for young people moving through constant changes in life. Similarly, my comics helped contain my feelings of unease and self-doubt, and allowed room for these feelings to transform into hope and anticipation in relation to my ongoing growth in my journey towards becoming an art therapist.

Implications

During data analysis, I became aware of how my student placement experience was strongly tied to the broader system of art therapy practicum training. My experience as the only voice of art therapy at my placement was common amongst fellow art therapy students. Like many of my peers, financial stressors and future uncertainty about student placements brought about anxiety that affected my placement performance. However, turning these experiences into comics inspired me to advocate for myself at the high school. Moreover, comics-making was greatly beneficial to me as a therapeutic practice for burnout prevention, developing my professional identity and fostering vicarious growth. I believe other art therapy students could benefit from adopting a comics-making practice for self-care during placement, especially those who struggle with impostor syndrome and harbour anxieties around their therapeutic skills while they are building their therapeutic practice (Van Lith & Voronin, 2016). This is relevant for art therapists who encounter vicarious traumatisation in their workplace as well (Kang & Yang, 2022; Short & Costello, 2022).

Limitations

I am a recent migrant from Hong Kong who is non-binary and of Cantonese heritage. Due to the scale of the study, I was unable to examine deeper sociocultural contexts at play behind my comics-making practice. Perhaps more in-depth research could further analyse sociocultural elements within the data, such as my decision to leave the comics-making dates (written in Traditional Chinese) untranslated, while conforming to a reading direction to suit anglophone readers (from left to right, top to bottom) in these sessions. Future research could explore how the simultaneous tension and interplay of culture (such as Japanese manga archetypes and Western cartooning styles) within these comics assist the making sense of migratory experiences while facilitating the process of integrating my linguistic and cultural identity into my emerging professional self.

In addition, the scope of the research did not allow for examining the benefits of sharing my comics with fellow art therapy students on placement and readers from other fields. This includes examining the healing potential of the relationship between artist-comic-audience and its similarities with Schaverien’s triangle of art therapy (Bell, 2022), as well as the ability for comics to convey lived experiences, provide diverse representation, and increase peer support (España et al., 2024).

Due to client confidentiality and the limited scope of this study, the research focused less on the specifics of client trauma and the ways in which I experienced secondary trauma as an art therapy student. Instead, it was an exploration of how the creative process of making reflective comics created a scaffolding to support professional development, while fostering vicarious growth and resilience as I worked through the anxieties and stressors of my art therapy practicum training. Future research may explore the applications of comics to vicarious trauma and burnout prevention for therapists, especially art therapy trainees.

Conclusion

To investigate the therapeutic potential of comics-making for the development of my trainee art therapist self, I began this critical autoethnography and comics-based research. During the data collection sessions, I created a series of reflective comics about my student placement experiences, then wrote about the process in my reflective journal. After thematic and critical analysis of my comics and post-art-making reflective writing, I noticed that creating comics about my student placement could facilitate re-storying processes that inspired more integrated ways of understanding my experiences, which was very beneficial to my well-being. Comics provided a playground of possibilities for multimodal healing, and encouraged the creation of alternative self-stories that led to growth and individuation. Comics-making assisted the ongoing development of my professional identity and encouraged my advocating for better conditions for myself. The comics also became transitional objects that eased the anxieties that surfaced when support was unavailable. Making comics not only improved my psychological state, but also strengthened my artist self and art therapist self. These benefits from comics-making have potential for other healthcare practitioners, especially other art therapy students on placement, who are also in the process of becoming.

Future research could investigate how comics-making can assist advocacy for better treatment for art therapy students on placement, diversify representation of art therapy students, and increase awareness about the field of art therapy. During my limited scoping review, I found insufficient literature on the student placement experiences of trainee art therapists, and studies on creative interventions to assist students on placement. It would be interesting for future research to examine the potential benefits of sharing comics by art therapy students on placement to see whether this increases peer support and has a role in the education and learning of fellow students, to support our collective ongoing becoming.

Endnotes

[1] Excerpts from the reflective journal included within this paper are indicated by single quote marks and italics. [back to place]

[2] ‘Magical girl’ is a subgenre in Japanese comics, featuring young girls who can magically transform (Saito, 2014). [back to place]

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the traditional custodians of the Dharug and Eora Nations, on whose unceded lands I live, learn, and become. I also honour Hong Kong, the in-between land of ever-changing tensions and im/possibilities that has shaped the foundations of who I am.

I would like to thank all those who made this work possible: my professors and fellow classmates at Western Sydney University who provided warm encouragement and trust in my artist–therapist self; my clinical supervisor, Martin Roberts, who offered gentle and grounding wisdom; my JoCAT Author Support Bursary mentor Zoë Dunster, and the JoCAT editors and Vic Segedin, whose strong faith in my research has been invaluable.

I also dedicate this work to: Emily, Tom, and Eliza, my swim buddies who have supported me through my post-graduation growth and struggles; Rachel, Sylvia, Carey, and my many friends from Hong Kong, together with whom I move between transitional states; and my parents, whose love – critical and unwavering in equal measure – has been both challenge and anchor: thank you for believing in my continuous becoming, even when the shape of it was still uncertain.

To the beautiful, terrifying, and rewarding process of creating, living, and becoming.

References

ANZACATA. (2024). Categories and requirements. https://anzacata.org/categories-and-requirements

Bechdel, A. (2012). Are you my mother?: A comic drama. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Bell, A. (2022). Storytelling + the art of comics in visual and written expression: Recovery with narrative art. Journal of Creative Arts Therapies, 17(1). https://www.jocat-online.org/a-22-bell

Bell, A. (2024). Living with Daisy: The therapeutic potential of cartooning in art therapy [Master's thesis, Western Sydney University]. https://doi.org/10.26183/k672-9b37

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caldwell, L., Robinson, H.T., Adès, R. & Kabesh, A.T. (Eds.). (2017). The collected works of D.W. Winnicott. Oxford University Press.

Duff, M. (2024). A safe portal of exploration for children and young people: The comic panel. In U. Herrmann, M. Hills de Zárate, H.M. Hunter, & S. Pitruzzella (Eds.), Arts therapies and the mental health of children and young people (1st ed., pp.133–149). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003265610-9

Erikson, E.H. (1994). Identity and the life cycle. W.W. Norton.

España, K., Perris, G.E., Ngo, N.T., & Bath, E. (2024). Reimagining narrative approaches through comics for systems-involved youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 63(8), 766–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2023.11.006

Feen-Calligan, H.R. (2005). Constructing professional identity in art therapy through service-learning and practica. Art Therapy, 22(3), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129490

Feen-Calligan, H.R. (2012). Professional identity perceptions of dual-prepared art therapy graduates. Art Therapy, 29(4), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.730027

Fernandez, K.T.G., & Lina, S.G.A. (2020). Draw me your thoughts: The use of comic strips as a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 15(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2019.1638861

Figley, C.R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Brunner/Mazel.

Gibson, D. (2018). A visual conversation with trauma: Visual journaling in art therapy to combat vicarious trauma. Art Therapy, 35(2), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2018.1483166

Graphic Medicine. (2024). What is “Graphic Medicine”. https://www.graphicmedicine.org/why-graphic-medicine/.

Gysin, S. (2020). Panel by panel: Changing personal narratives through the creation of sequential art and the graphic novel [Graduate project, Concordia University]. Spectrum Research Repository. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/987130/

Hagert, E. (2017). An exploration of art therapy process with a detainee diagnosed with schizophrenia in a correctional facility with reference to the use of the comic strip. (2017). In K. Killick (Ed.), Art therapy for psychosis (1st ed., pp.181–202). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762340-9

Hasselmo, S., Thomas, I., Páez, J., Kowalski, S., Cardona, L., & Martin, A. (2023). A hero’s journey: Supporting children throughout inpatient psychiatric hospitalization using a therapeutic comic book. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 36(3), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12415

Heath, W. (2000). Cancer comics, the humor of the tumor. Art Therapy, 17(1), 47–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2000.10129433

Heifler, S. (2022). Let me out of here: A story of using comics to heal during the pandemic. The Comics Grid, 12(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.16995/cg.6545

Hinz, L.D. (2009). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy. Routledge.

Hopkins, M., & Goss, S. (2013). The compassion fatigue workbook: Creative tools for transforming compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatisation. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41(3), 341–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2013.778011

Howarth, A. (2021). A systematic literature review: Exploring evolving and emerging themes in vicarious trauma research from 1990 to 2021. Australian Counselling Research Journal, 15(2), 1–13. https://www.acrjournal.com.au/

Jones, S.H., & Harris, A. (2021). Critical autoethnography and mental health research. In P. Hackett & C. Hayre (Eds.), Handbook of ethnography in healthcare research (1st ed., Vol.1, pp.197–209). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429320927-22

Jue, J., & Kim, T.-E. (2023). Exploring the relationships among art therapy students’ burnout, practicum stress, and teacher support. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1230136–1230136. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1230136

Kang, J.H., & Yang, S. (2022). A therapist’s vicarious posttraumatic growth and transformation of self. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 62(1), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167819889490

Khan, R. (2021). Comics in online art therapy with Pakistani adolescents (Bandes dessinées dans l’art-thérapie virtuelle avec des adolescents pakistanais). Canadian Journal of Art Therapy, 34(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/26907240.2021.1914988

Kim, J., Chesworth, B., Franchino-Olsen, H., & Macy, R.J. (2022). A scoping review of vicarious trauma interventions for service providers working with people who have experienced traumatic events. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(5), 1437–1460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021991310

Knight, C. (2013). Indirect trauma: Implications for self-care, supervision, the organization, and the academic institution. The Clinical Supervisor, 32(2), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2013.850139

Kuttner, P.J., Sousanis, N., & Weaver-Hightower, M.B. (2018). How to draw comics the scholarly way: Creating comics-based research in the academy. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (1st ed., pp.396–422). The Guilford Press.

Lucas-Falk, K., & Hyland-Moon, C.H. (2010). Comic books, connection and the artist’s identity. In C.H. Moon (Ed.), Materials and media in art therapy: Critical understandings of diverse artistic vocabularies (1st ed., pp.231–256). Routledge.

Malchiodi, C. (2019, September 24). Expressive arts therapy is a culturally relevant practice. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/arts-and-health/201909/expressive-arts-therapy-is-culturally-relevant-practice

Malchiodi, C. (2021, September 15). Traumatic stress and the circle of capacity. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/arts-and-health/202109/traumatic-stress-and-the-circle-capacity

Mayes, C. (2020). Archetype, culture, and the individual in education: The three pedagogical narratives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429423758

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics. Harper Collins.

Moon, B.L. (1998). The dynamics of art as therapy with adolescents (1st ed.). Charles C. Thomas.

Mulholland, M.J. (2004). Comics as art therapy. Art Therapy, 21(1), 42–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2004.10129317

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Oostdijk, D. (2018). “Draw yourself out of it”: Miriam Katin’s graphic metamorphosis of trauma. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 17(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725886.2017.1382103

Ortner, D. (2024). Creative arts as self-care: Vicarious trauma, resilience and the trainee art therapist. International Journal of Art Therapy, 29(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2024.2317941

Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995). Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors (1st ed.). Norton.

Pennebaker, J.W., & Chung, C.K. (2007). Expressive writing, emotional upheavals, and health. In H.S. Friedman & R.C. Silver (Eds.), Foundations of health psychology (pp.263–284). Oxford University Press.

Phang, C. (2023). Individual versus sequential: The potential of comic creation in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2023.2261537

Riley, S. (1999). Contemporary art therapy with adolescents. Jessica Kingsley.

Rubin, J.A. (2016). Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Saito, K. (2014). Magic, shōjo, and metamorphosis: Magical girl anime and the challenges of changing gender identities in Japanese society. The Journal of Asian Studies, 73(1), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911813001708

Short, B.A., & Costello, C.M. (2022). Healing from clinical trauma using creative mindfulness techniques. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003036777-10

Tjasink, M., Keiller, E., Stephens, M., Carr, C.E., & Priebe, S. (2023). Art therapy-based interventions to address burnout and psychosocial distress in healthcare workers: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1059. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09958-8

Van Lith, T., & Voronin, L. (2016). Practicum learnings for counseling and art therapy students: The shared and the particular. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 38(3), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-016-9263-x

Venkatesan, S., & Peter, A.M. (2018). ‘I want to live, I want to draw’: The poetics of drawing and graphic medicine. Journal of Creative Communications, 13(2), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258618761406

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton.

Williams, I. (2011). Autography as auto-therapy: Psychic pain and the graphic memoir. The Journal of Medical Humanities, 32(4), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-011-9158-0

Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Playing and reality. Tavistock.

Author

cat ko

MA ATh, AThR

cat is an art therapist with a deep curiosity towards the processes of human becoming. They are on a journey to understand trauma through a socio-political lens, and to investigate conditions that foster growth, healing, and resilience. Based on Dharug and Eora Country, their work focuses on adolescents, LGBTQIA+ communities, and people from Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora. As an artist–therapist, cat explores how comics can rewrite our lives and selves, supporting creative flourishing in challenging times. On their days off, they believe in the healing powers of ‘lying flat’ (躺平) and not doing anything at all.