Open Access

Published: September 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.2

Word count: number

About the author

Therapeutic Art Play: Art therapy practices in education to nurture autonomy, creativity, and connection

Georgia Freebody

Abstract

In many contemporary, Western, educational contexts, relationships to community, technology, and nature are in rapid flux. In psychology and education, for instance, there are increasing calls to support emotional, social, and mental well-being alongside cognitive development. Research shows that the ability to create and learn is linked to feeling safe and secure (Cipriano et al., 2023). The Therapeutic Art Play (TAP) program responds to these calls by creating spaces for agency, creativity, and connection through ‘artworking’ process art that enhances both learning and well-being. Artworking is described in this setting as the activation of a creative space for cultivating well-being and learning enhanced by art therapy practices. Developed in early education, the TAP program provides frameworks for bringing artworking into primary school settings, and out-of-hours care, and informs pre-service teaching programs focusing on well-being in university settings. TAP combines art therapy and education, emphasising diversity, transformation, and individual/group empowerment. This paper, written by a researcher and facilitator of TAP, outlines Therapeutic Art Play principles and practices, and describes development through arts-based research in early education and subsequent implementation across various settings. It explores the impact of process art on learning and details key TAP features, including enabling agency through material invitations, attuning via ‘slipstreaming’, and fostering critically reflective practices. This paper explores the opportunities TAP provides for well-being and learning through embodied, sensory exploration of the world.

Keywords

Therapeutic Art Play, art therapy, education, early childhood, new materialism, arts-based research, process art

Cite this articleFreebody, G. (2025). Therapeutic Art Play: Art therapy practices in education to nurture autonomy, creativity, and connection. JoCAT, 20(2). https://www.jocat-online.org/a-25-freebody

Introduction

In an era of rapid change, the need for fostering a strong sense of well-being becomes increasingly urgent. As cultural, technological, and environmental landscapes shift and diversify, developing creativity, emotional intelligence, and critically reflective practices becomes essential (King, 2025). This is further supported by growing evidence in neuroscience that sensory, embodied engagement in creative art-making promotes neuroplasticity, enhances brain health, and fosters adaptive, emotionally attuned ways of being (Strang, 2024). In the face of this, the value of imagination, the ability to harness and manage creativity, and skills for connection and collaboration with each other and the material world are invaluable. Evidence increasingly points to the need for ongoing practices of critical reflection, and for reflexivity in our responses to the environment, ourselves, and one another (Deboys et al., 2016).

The creative arts provide educational practitioners and systems with powerful tools for enhancing well-being, creativity, and reflective practice (Chilton, 2013). The professional practice of art therapy provides art-making experiences guided by a trained art therapist to support emotional, psychological, and social well-being (Snir, 2022). Art therapy offers children in their early years a safe, non-verbal means to express, process, and communicate complex feelings and experiences, particularly when words are insufficient (Malchiodi, 2020; Waller, 2006). Armstrong and Ross (2020) emphasise that, in early childhood, art therapy facilitates change through the creation of a safe and playful group space that fosters connection, belonging, and the co-creation of meaning between children and adults. In early childhood education, these approaches create environments where young children can explore emotions, develop communication skills, and engage in learning through whole-body, sensory-rich experiences that nurture well-being, learning, and relational development (Chilton, 2013; Moula, 2020).

This article outlines a distinctive approach to bringing creative spaces into education via the practice of ‘artworking’ developed in the Therapeutic Art Play (TAP) program. Providing transformative creative spaces informed by art therapy practices in educational settings since 2019, TAP focuses on the learning and well-being of teaching and learning teams together. TAP brings together educational principles from the learning dispositions model by Jefferson and Anderson (2017) and the transformative mechanisms of change in art therapy as described by Armstrong and Ross (2020).

This article begins by exploring the role, power, and vitality of art in education. It then introduces the TAP program, detailing its origins, and outlining a research study that examined and evaluated its initial implementation in early learning settings. Following this is a consideration of the specific practices and principles of TAP as it was researched and continues to be applied. A summary then highlights the program’s key frameworks, patterns, and rituals. The article proceeds to explore how TAP evolved across different educational contexts, outlining the benefits observed in these settings. The paper concludes with a reflection on the ethical considerations needed for a healthy, effective TAP program.

This article is written by the researcher as both author and TAP facilitator, drawing on professional experience as an artist, educator, and art therapist. The TAP program, developed and implemented by the author, is informed by these intersecting disciplines, which together shape its relational and creative approach. This background situates the research within a practice-based, interdisciplinary lens that values both artistic process and therapeutic engagement in educational settings.

Background: The power of art in education

The effects of experiencing, making, and communicating with the world using art have been shown to foster holistic learning and well-being in ways that go beyond traditional educational frameworks (Cahill, 2015; Moula, 2020). Taking part in the arts has been linked to improved quality of life (World Health Organization, 2014), and to the development of transferrable skills (Harris, 2014). Creative arts are extensively recognised as encouraging more profound ways of knowing, engaging the senses, emotions, and the intellect (Dewey, 1934; King, 2025). The creative process nurtures learning when it is embedded in an experience of connection, autonomy, and imaginative exploration (Cahill, 2015; Harris, 2014): in early learning parlance – “belonging, being, and becoming” (Department of Education, 2022. p.7). Facilitating for the creative process in this way supports the fundamental interrelated aspects of meeting the learning needs of the whole child (Barblett et al., 2021; Department of Education, 2022; Noddings, 2005; Pascal et al., 2019).

The TAP program integrates aspects of art therapy practices into play-based learning frameworks for well-being and learning together. Relational art spaces in TAP are intentionally cultivated to be safe, attuned, and responsive environments. These environments are reinforced by therapeutic practices of continuous and sensitive presence, active listening, validation, and witnessing (Learmonth, 1994), as well as active containment of the artworking space (Cahill, 2015; Case et al., 2022). TAP philosophy is built on the understanding that these relational artworking spaces support emotional expression, connection, belonging, and transformation (Armstrong & Ross, 2020). TAP emphasises the power of co-creation and relationship between children, adults, and materials, fostering individual and collective well-being. These practices, in turn, align with the learning dispositions identified by Jefferson and Anderson (2017), such as curiosity, collaboration, and resilience. This is done by providing opportunities for children to investigate, imagine, and explore through sensory-rich, open-ended art experiences that honour their perspectives and promote authentic participation in the learning community.

Lively process art

The following photograph and accompanying anecdote provide one example of a process art TAP experience in a toddler classroom. Illustrated here is a way that TAP can facilitate the development of connections (and belonging), provide space where a child and teacher could bring their full selves (being), and relax, into a creative flow state to extend their play schema (becoming).

Figure 1. P slipstreams into M’s creative flow. Image of the TAP space from public domain.

Most of the participants have drifted away and the art materials are spread on the floor. M carefully scoops green sand into a bowl and, with a delighted smile, tips it over her head, watching the grains cascade down the edge of the bowl and onto her chest before brushing them off and repeating the ritual. Beside her, P skilfully balances a child on her knee and supervises children moving through the bathroom. M looks through the transparent bowl at P and smiles. P grabs a handful of sand sprinkling it onto the top of the bowl, they watch the sand run down the outside of the bowl and laugh together. I notice the rhythm of their actions and the graceful way P joins the moment without disrupting its flow, embodying a seamless interplay of teaching and creativity. We notice and reflexively discuss my observation of the artworking. P is surprised by how much I notice, I am surprised by how creative and responsive P’s teaching skills are, we are both delighted by the power of M’s play. I realise the depth and complexity of these intra-actions, the validation and extension of play rituals, the connections and empathy being displayed. This simultaneous experience of being, becoming, and belonging is a privilege to witness in the richness of this shared TAP space. This witnessing provides an opportunity to develop a practice of deeper noticing, and critical and mindful reflection.

Technical terms used above were developed within the framework of TAP. These are defined in the following section that describes the research study underpinning the TAP program.

‘Process art’ refers to open-ended art experiences focused on exploring, experimenting, and making art as playing rather than producing an artefact or specific outcome (Jarvis, 2011). Experiencing and making art has been shown to allow for the exploration of personal and cultural identity, the development of emotional resilience and meaningful connections with the natural world.

When making art is seen not only as the creation of artefacts via the exercise of technical skills, but also as a relational, experiential process, its transformative effect becomes clear. Meyerowitz-Katz and Reddick (2017) for instance, emphasised that making art should be valued as a process in itself, fostering intrinsic motivation and a distinctive space for growth. In this light, process art is seen to be deeply relational, existing within the unique cultural, social, and physical contexts of classrooms (Fraser et al., 2006). Through engaging artfully with materials together, children can establish unique connections with their environment and their peers, developing a sense of belonging (Cahill, 2015; Franck et al., 2020).

The concept of ‘liveliness’ is central to process art in TAP, illustrating the dynamic state of early learning and educational spaces. MacAlpine (2021) has described liveliness as a quality of interactive change that brings together time, people, materials, and the environment in a continuously evolving, engaging, and interactive process. Within this lively engagement, children develop foundational play schemas, or repeated patterns of play, that help structure knowledge and understanding (Piaget, 1953). By means of attention and attunement to these schemas, educators and art therapists can witness how expertise, capacity, and knowledge are built, moving beyond static or individualised views of learning or well-being (Armstrong & Ross, 2020).

Process art operates through a creative state of ‘flow’, whereby participants become increasingly absorbed in the process. Csikszentmihalyi (1997) has described this flow as a state of optimal engagement driven by intrinsic motivation. This allows for, and gives structure to, exploration, expression, independent learning, and problem-solving (Arnott & Duncan, 2019).

Much of the time, a process art event is transient; the process, sensory experience, and expertise developed within the event can be understood as the outcome or ‘artwork’. If there is an artefact at the end of a lively process art event, it may represent an embodiment of the learning, well-being, and capacity of the artists; it may also, however, be understood as a container, a souvenir, or a symbol of the artist’s sense of being, belonging, and becoming (Proulx, 2002). Much research, as shown in a systematic literature review by Barblett et al. (2021), conducted to inform Australia’s updated Early Years Learning Framework, indicated that children’s creative potential is frequently overlooked and undervalued in early education. This review highlights that children’s abilities to express themselves and actively participate within their environments are often not given sufficient attention or respect. Recognition and encouragement of the capacities of young children, across the curriculum areas but perhaps distinctly in artistic production, are central to their development as individuals. By fostering autonomy, connection, and creativity, process art enables children to explore who they, distinctively, are. Perhaps most vividly, process art facilitated by an educator and art therapist can provide children with supportive, dynamic environments, nurturing their growth in all its complexity.

The TAP program

The Therapeutic Art Play (TAP) program has been running in educational settings since 2019. Created and implemented by an educator who is both artist and art therapist, TAP fosters unique environments for nurturing agency, creativity and reflection. Central to the TAP approach is an understanding that security and care are foundational for meaningful engagement in play, learning, and well-being. It is this foundation of care, consistently highlighted in early childhood frameworks, such as the Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF), that prioritises well-being (Department of Education (Australia), 2022; Meyerowitz-Katz & Reddick, 2017). TAP responds to and extends this notion providing a program informed by visual arts, pedagogy, and therapeutic practices. Art therapy encourages the processing and communication of experience, ideas, and emotions in ways beyond verbal expression or written text (Malchiodi, 2020; Waller, 2006). TAP, originally developed in early learning environments, has installations in primary schools, out-of-hours school groups, private clients, and with practice-informing pre-service teaching workshops. A rigorous exploration of the TAP program via research study has afforded a deeper understanding of its core principles, critical practices, and potential impacts.

Exponential growth through research

The TAP program was explained, explored, and exemplified in an arts-based research project completed in 2023. Data were gathered from therapeutic art play conducted in a toddler room with children aged one to three and their accompanying adults. The morning programs were facilitated on Wangal land (in Sydney’s inner-west). These involved interactions with sand, flowers, shells, and stones. The shells and stones were gathered from and, where possible, returned to Dharawal Country along the coast of southern New South Wales. Included also were plaster, matt board, scoops, containers, and water. Data took the form of photographs of artworking and artworks, naturalistic observations, questionnaires, and recordings. In addition, the researcher/TAP facilitator gathered data from their own artworking in response to the research process. Taking part in lively creative process art allowed for the consideration of human and non-human interactions (Taylor, 2017). An analytic framework based on aspects of theories of new materialism enabled a diffractive analysis, as outlined below, that puts on display the characteristics and impacts of the TAP program.

Methodology: Diffractive analysis

The study adopted a new materialist methodology, recognising that well-being and learning are created and develop through entangled relationships between people, materials, and environments through time. Moving from reflective to diffractive analysis (Barad, 2007), the research informing this article attended to an exploration of shifting intra-action in the TAP artworking space. Key concepts such as intra-action, active agents, artworking, nomadic artworking, and relational practices like deep noticing, attunement, and slipstreaming are unpacked in the following section. These are described as together creating a responsive research framework for exploring TAP’s dynamic, transformative processes.

Reflective research methods can provide educationally valuable insights (Hill, 2017). Reflection sees the researcher aiming to represent reality as it appears – much like light bouncing off a surface to produce an image. In contrast, diffraction accounts for the ways in which light, or meaning, bends, disperses, and transforms through entanglement with various elements in the research assemblage. Diffractive analysis highlights the researcher, participants, and materials coalescing in dynamic relationship (Fox & Alldred, 2014). This allows for difference, change, and single variance, such as one-off events, rather than solely focusing on repeated common, core themes (Barad, 2007). This method is well-suited for studying the fluid and multisensory nature of play, where both human and non-human elements (such as time, art materials, sensory experiences, and the play environment) are in active relationship, shaping and being shaped by one another.

In the context of researching TAP with toddlers, diffractive analysis emphasises the importance of considering how actions, gestures, and materials move to create moments of expression that are transitory and intra-active rather than fixed and static. Intra-action refers to how agents actively shape and reshape each other within often-distinctive dynamic relationships of play, rather than acting as separate, independent entities (Barad, 2007). As Lenz Taguchi (2009) notes, play is not a simple sequential transaction or interaction, but rather a fluid intra-action, whereby both the child and the materials are active agents. This perspective can provide the researcher with an understanding of toddlers as engaged participants in an assemblage of play, where materials (such as clay, paint, or fabric) are actively influencing the direction of creative play, and vice versa. The artworking play space TAP provides can be a space to hold that assemblage of relational intra-actions within which active agents co-create.

This was mirrored in the arts-based research via nomadic artworking. Nomadic artworking was developed by the researcher as an iterative, research practice that extends the artworking space from the classroom into the research methodology, enabling a fluid, non-sedentary mode of inquiry. Rooted in the concept of nomadic analysis (Cole, 2013; Deleuze & Guattari, 1987), this method embraces movement and intra-action as a way to attune to the sensory-rich moments that shape both researcher and research. Nomadic artworking involved the researcher re-engaging with similar TAP materials in a different location, responding intuitively to embodied traces of past encounters. This practice offered a mode of reflexivity, allowing the researcher to process and be shaped by the TAP experiences in a manner that was sensorial, and open-ended. As such, nomadic artworking functioned in the research as an empathic bridge between lived experience and reflective inquiry.

Using diffractive analysis allowed for a nuanced view of artworking in which each moment was taken to offer potential for new connections and insights into the development of the participants. This included the researcher’s positioning within the assemblage (Hill, 2017), acknowledging how that influenced the artworking, and how the researcher’s perspective changed in response to the intra-actions observed. When studying TAP, particular features of diffractive methodology emerged as the participants and the materials intra-acted (Palmer, 2011). In these ways the methodological distinctiveness of diffractive analysis provided an innovative and responsive academic study. What developed was a bespoke methodology that is finely tuned to explore the complexities of artworking; open-ended, sensory-rich creative processes; and the often-overlooked, distinctive affordances of art therapy practices in early childhood.

Diffraction, reflexive practice, and reflection

This article uses the terms ‘diffraction’, ‘reflexive practices’, and ‘reflection’ to refer to different but related processes. Diffraction, drawn from Barad (2007), describes research methods that position the researcher within the inquiry, tracing intra-actions with human and non-human agents in the TAP artworking space. Reflexive practice, or reflection-in-action (Van Lith & Voronin, 2016), re-centres the human, highlighting responsive roles within the artworking event. Reflection refers to cognitive and creative processes; reading, writing, artworking, and dialogue. A critically reflective practice asks questions about the journey so far, and the journey to come, toward more open, inclusive, mindful decision making (Jefferson & Anderson, 2017). The TAP study and its findings (some of which are outlined below) offer a philosophical position informed by new materialism, as well as foundational ideas and terminology to support the extension of artworking in educational settings.

Artworking

The process art that is activated in a TAP space is characterised as ‘artworking’. Artworking is a concept that became visible in this study as a dynamic, intra-connected process of artistic creation, enabling an experience of the states of belonging, being, and becoming. Artworking processes and products are continuously (re)shaped by participants’ engagement with various elements such as materials, time, people, sounds, and spaces. Artworking fosters a state of flow and movement: continuities emerge that support individual and collective expression, creating a shared set of connections between all active agents.

Figure 2. Embodied artworking in the TAP space.

Figure 2 shows the developing relationship between active agents, material and human: hands grab and swirl in sand, plaster, and leaves. The mixing and dragging develop in their form and function, making marks and colours.

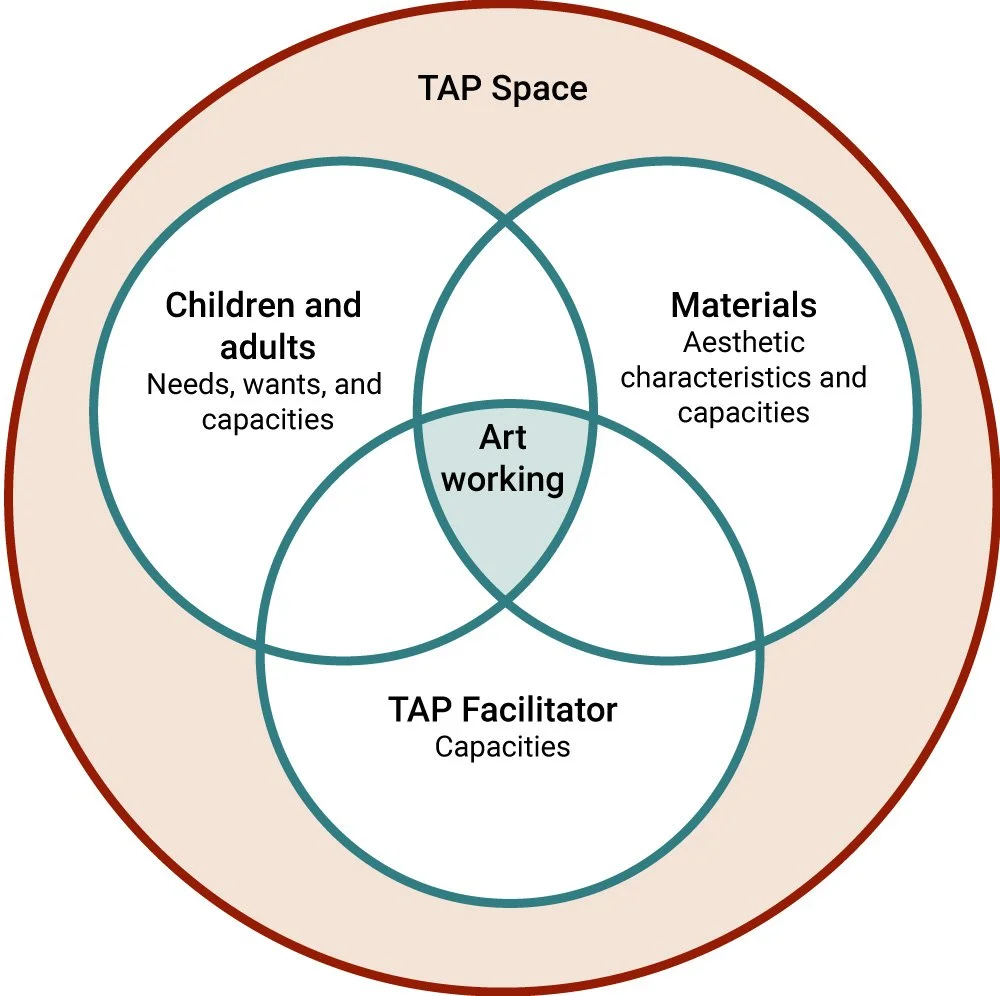

Active agents

TAP’s artworking space is designed not only to engage children as participants, but to consider all elements of the classroom (time, space, materials, sensory experiences) as intra-acting agents (Barad, 2007). Such agents afford feedback, playing a central role in each experience. Because a defining characteristic of TAP is the way it is informed by human and material participants, it tunes into and acknowledges feedback from all active agents in the artworking event, including settings and materials. The active agents can be seen occupying the TAP space in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Active agents in the TAP space: materials (aesthetics, characteristics, and capacity).

The relationships among these agents constitute the artworking experience. The TAP study was shown to develop relational artworking techniques such as attunement and slipstreaming (defined below) to deepen these relationships. These practices foster an environment to nurture and allow for transformation within as well as between participants (Barad, 2007). Thus, artworking in the TAP program becomes a collaborative, transformative experience; it emphasises agency, fluidity, and distinctive connections among all participants, as a way to ‘enfold’ (Matapo & Roder, 2018) classroom experiences into artworking. In this way TAP aims to weave creative expression into the fabric of daily classroom life.

Relational practices: Deeply noticing, attunement and slipstreaming

The research project found relationality to be a core characteristic of TAP, whereby artworking means taking part in a continuous practice of presence, responsiveness, and attunement. Children and facilitators engaged in what is known as ‘deeply noticing’ (Buley et.al. 2016), a practice of tuning-in to the present moment and to the subtle cues of materials, sounds, movements, and one another. Here, attunement reaches beyond attuning to an attachment figure (Armstrong & Ross, 2020; Bowlby, 1997); it incorporates the basis of support for both individual and collective presence. Originally a psychoanalytic concept, attunement is expanded within TAP to attend to the entire spectrum of the artworking event – including the children, objects, and sensations. For TAP, this heightened awareness creates what Winnicott (1971) calls a “holding environment”, whereby artworking becomes a container that makes space for, and can witness and accept, each participant’s emotional and creative expression.

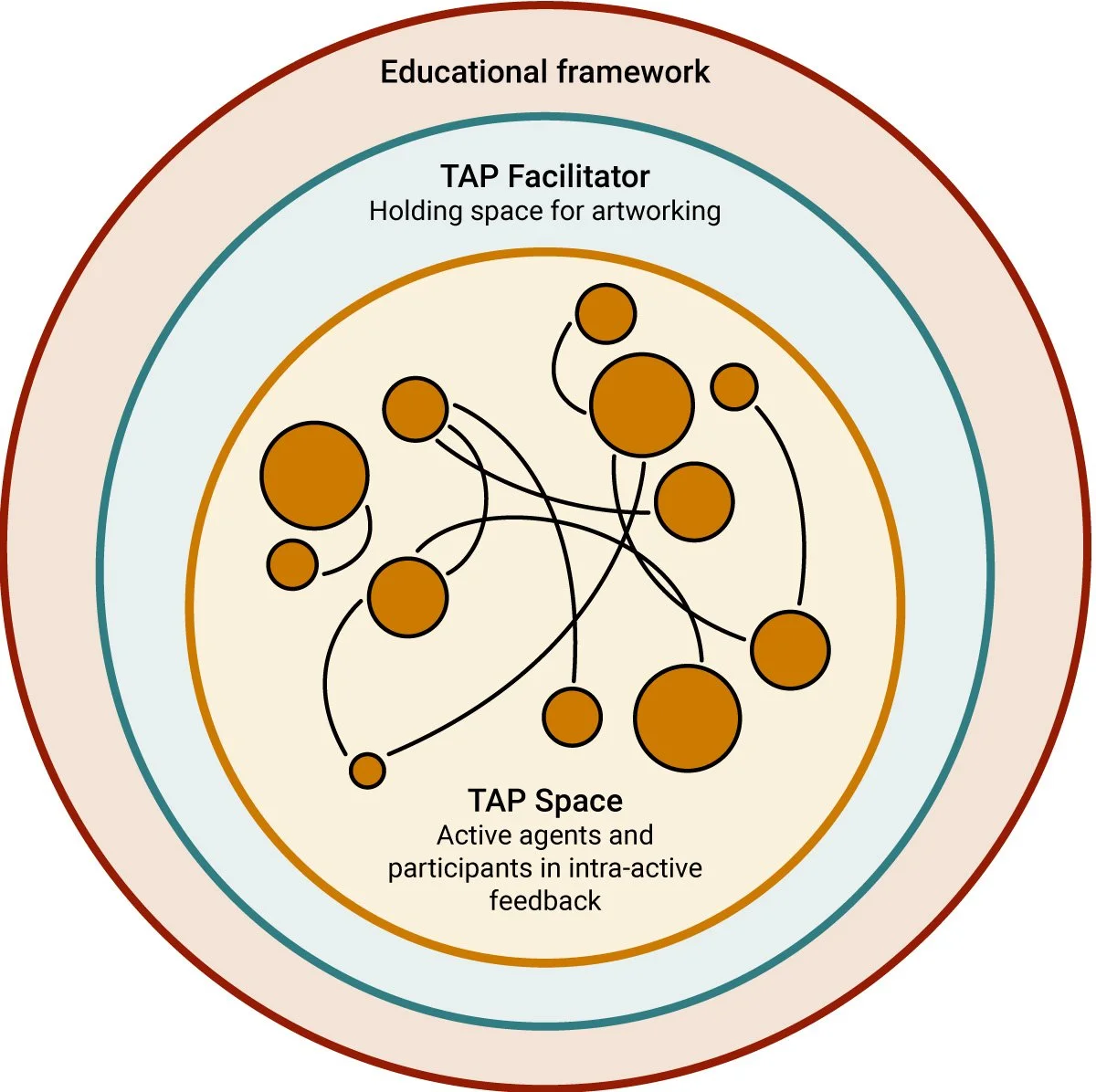

One of the innovative relational tools developed in TAP is termed slipstreaming. Slipstreaming here refers to a concept adapted from aerodynamics. It describes the practice of materials, children, educators, and researchers ‘moving alongside’ and subtly collaborating in emerging creative processes. Slipstreaming depends on finely honed attunement and deep noticing. When done sensitively and skilfully, slipstreaming can allow for genuine collaboration with children’s play, artworking, repetitive play schemas, and emerging ideas. Slipstreaming fosters a collaborative artmaking process whereby children and adults co-create the experience without intervening or directing, allowing creative momentum to grow naturally from the setting. This approach respects learners’ agency, encouraging them to inform the artworking event while feeling supported and secure. Figure 4 shows an attempt to represent an artworking space with its shifting, intra-acting agents and their relationships. It shows how these are held by the TAP space, the TAP facilitator, and the overall educational framework.

Figure 4. The relational ontology of artworking.

The TAP program’s commitment to attunement, slipstreaming, and non-directive support is aimed at cultivating a responsive and evolving environment. This is a commitment to enabling participants to access deeper layers of creativity, self-expression, and relational understanding, as well as providing a space for critical reflection. By promoting emotional safety and fostering relational attunement, the arts-based research project conducted in 2023 explored how TAP supports the holistic development of each child, affirming the transformative power of artworking as a tool for growth and well-being. Through these integrated methods, TAP not only reinforces a space for agency and creativity in the classroom, but also cultivates a lasting foundation of resilience, empathy, and self-discovery. Brief examples of how TAP creates space for these benefits will be exemplified following a discussion of the TAP framework.

TAP: A framework, steps, patterns, rituals

As noted above, TAP’s relational ontology, and its provision of attunement and slipstreaming, together lead each artworking space to manifest distinctively. But some practices, steps, patterns, and rituals are common. These can be itemised in terms of these guidelines. Vital first steps in building a powerful and safe TAP space will involve establishing a culture of consent and autonomy. Participants must be able to first and foremost (and then ongoingly) choose to artwork, choose how they artwork, and how to move in and out of artworking. This in turn establishes intrinsic motivation. TAP’s framework, steps, patterns, and rituals are outlined in the following sections.

Consultation through continuous communication

To ensure that the program remains iterative, tuned into feedback, and a part of an emergent curriculum, the TAP facilitator needs to be continuously present to and informed by communication and consultation with participants.

Working within an ecology of materials

In consultation and reflection, the facilitator needs to source relevant materials as part of a reflective process mindful of:

the materials’ aesthetic and sensory characteristics and capacities,

their impact on the environment,

the heritage and the country gathered from and on,

how far they have travelled, and

and what will happen to them after the TAP workshop.

These considerations are vital for fostering a safe, responsive TAP space that respects both environmental and cultural landscapes. By attending to the origins, sensory qualities, and afterlife of materials, facilitators model caring for the more-than-human world while honouring diverse cultural relationships to land and making. This approach aligns with the EYLF (Department of Education, 2022), supporting children’s eco-consciousness, well-being, and sense of belonging.

Creating an invitation to artplay

The art materials are brought into the classroom, playground, or other educational space, and the facilitator then creates an ‘invitation to play’. This is a creative act in itself, taking account of the material characteristics, the human participants’ needs and wants, and the physical environment and available time. Materials are set up in ways attractive to participants, to enable artworking engagement and interactions. These invitations may be informed by previous artworking events and anticipated movements, affects, sounds, processes, and outcomes.

Figure 5. Invitation to play. Black felt, repurposed bowls, wooden scoops, stones, shells, sand (Dharawal country) flowers and leaves (Wangal Country).

An artworking event

Participants are free to join, drift away, and rejoin, and any creative artworking engagement is accommodated. Teachers and staff are invited to interact with the materials and take part (they remain attuned to the children, and play, explore, and create). The TAP facilitator remains mindful of the containment of the artworking event at hand, making space and managing the artworking’s liveliness. During artworking the TAP facilitator models practices of slipstreaming, feedback, communication, and collaboration via deep noticing and attunement. The facilitator needs to remain attentive to the therapeutic mechanisms for change as well as the learning dispositions displayed, noticed, and enacted.

Continuous practice of critical reflection

The TAP program becomes a space allowing for critically reflexive discourse – reflexive in that, during the artworking, participants have the security, space, time, and agency to make mindful choices in direct response to artworking. The artworking space becomes thereby a place where participants can process experience, explore, and imagine alternate experience, and give and receive feedback to each other and materials. It thereby also becomes a place where participants ‘check in’ with ideas for the next workshop, to be followed up throughout the week. Participants provide overviewing before and debriefing afterwards, encouraging critical reflection. This reflection in turn is recorded and responded to in the reflective reporting by the facilitator, delivered to the participants the following day.

‘Containing’ the artworking event

Part of this reflective practice involves the TAP facilitator containing the artworking event. The facilitator, attuned to the artworking, develops an understanding of the event as lively, and organic (and develops an understanding of when it is effectively over). The end of the artworking event can be observed via a range of both obvious and subtle indicators: a change in the movement or sounds in the room; a sense of purposeless destruction of materials; when the art materials are stationary, but the participants are very active; when the noise level rises or drops dramatically; or when participants drift away, and so on. Each artworking event will be different, including with regard to its lifespan.

Reflective reporting

As part of the critically reflexive space in the artworking event, the facilitator creates a series of reflective reports. These reports record observations such as naturalistic observations; records of voices and words spoken; photographs of artworks, artworking and artists; links to learning outcomes, learning dispositions, and therapeutic mechanisms of change. These in turn extend to ideas and questions for critical reflection and the location of the visual arts materials, principles and elements, and techniques accessed in the workshop. These reports can be used as records or souvenirs from the artworking to share with participants and their community. These reports also act as programming material, to inform and be continually informed by an emergent curriculum. This reflective reporting includes the development of an extensive material ‘risk assessment’ as well as mindful presence to an explicit code of ethics (such as that of ANZACATA, the Australian, New Zealand, and Asian creative arts therapy regulatory association).

TAP’s impacts and benefits

The guidelines itemised above are ordered and crafted specifically to create a space to enhance agency, then creativity and reflection. The invitation to play allows participants to choose, and ongoingly consent to, the artworking process. This choice enhances the sense of belonging, being, and becoming in an authentic way, and in a way that is, educationally speaking, unique: Participants who are intrinsically motivated to engage in artworking can then take part in creative engagement and reflective practices.

The TAP program allows participants to develop strategies for connecting well-being and learning and to reflect on that connection. TAP helps participants get better at knowing why and how it helps them get better. TAP aims to do this by allowing opportunities for participants to:

fully bring to bear and exercise their capacities and in doing so, to develop and express their identity;

process and represent their lived experiences (facilitated by the quality of the space held by the TAP facilitator for witnessing, acknowledgement and empathy);

enact stories and play schema;

confidently reflect on their own expertise as displayed by retelling, re-enacting, and pausing to allow space for decision making;

imagine alternates, practice decision making, displayed by taking part in choice and envisaging active transformation;

build resilience via opportunities to face personal challenges in their own space and time; and

connect with others, develop collaborative skills displayed by offering and yielding materials, movements, and ideas.

By creating an invitation to play and co-creating in the artworking the TAP facilitator can remain tuned in to the many ways that participants may express or indicate the development of well-being and learning dispositions. The participant-informed artworking experiences that create opportunity for the above benefits can manifest in different ways. No two artworking experiences are the same. This diversity provides adaptability, allowing TAP to fine-tune to different educational settings.

TAP across educational settings

The TAP program centres on a relational ontology and the practice of artworking to support material, sensory, and embodied expression. This approach is accessible to participants of all ages and capacities, adapting to a wide range of educational environments while maintaining its core focus on relational, evolving creative spaces.

In early childhood settings – including infants, toddlers, and preschoolers – TAP emphasises sensory exploration. Invitations to play may be brief and revisited often, enabling young children to develop confidence and expertise over time. Adult perceptions of ‘messy play’ may sometimes misinterpret children’s intentional interactions with materials. However, when caregivers participate in artworking, they model vulnerability and creativity, strengthening bonds and opening pathways for reflective practice.

In primary schools, TAP navigates structured schedules by operating during less formal times – before school, lunchtime, or after school – as art clubs or drop-in studios. These spaces support self-directed projects and ongoing processes, and small-group sessions can resemble non-directive art therapy, coordinated with educators or counsellors.

In after-school care (OOSH), children often welcome TAP’s open-ended, sensory-rich activities after a structured day. The environment supports autonomy, ritual, and drift, with children initiating their own creative pathways.

At the university level, TAP supports teacher training by offering embodied, reflective experiences. The gradual introduction of materials fosters attentiveness, agency, and an understanding of change through sensory engagement, offering adult learners a direct experience of the principles at the heart of TAP.

Ethical considerations

The efficacy of the TAP program is reliant on its safe and ethical implementation. Holding a TAP space for artworking requires facilitation by a trained TAP facilitator. TAP facilitators are chosen with care and for their intersection of skills and qualifications. Groundwork for TAP training is in art therapy, education, and visual arts. TAP needs to be supervised by a registered art therapist and trained and experienced educator. Each program is run by a facilitator or team with a full set of skills. All TAP facilitators receive supervision and debriefing by the founder and head supervisor who in keeping with ethical practice and registering body, ANZACATA, receives ongoing supervision, themselves. The piloting of new programs (with the cultivation of relational culture) is a collaboration between the teaching and learning team, TAP facilitator, and TAP supervisor. While TAP is not clinical art therapy, interventionist therapy, or art psychotherapy, the TAP facilitator needs to contain the artworking such that it can create reflexive spaces for well-being and learning. TAP workshops and experiences allow for a full immersion by the participants in the lively artworking event, requiring an art therapist to hold that space. Having said this, TAP works best when it is part of an emergent curriculum, woven into the ongoing program and pedagogy of the group. Teachers and students can and should continue to art play with the materials, mixing them and transitioning them into their learning and well-being processes throughout their week. Participants have been shown to benefit when they exercise the creative connections, collaborative skills, and reflexivity practiced in the TAP space. This is displayed via observations of children’s learning and well-being, along with feedback from families, teachers, and facilitators of ongoing programs. These creative skills and reflective practices can be seen in settings where TAP has been adopted by an emergent curriculum, running inside the educational program, rather than alongside or as extra curricula.

TAP facilitators are selected from diverse backgrounds in mental health (including counselling and psychology) and contemporary art practice, with many also engaged in professional development in teaching or early childhood education. All facilitators receive comprehensive training in TAP practices from the program founder and researcher, Georgia Freebody, as well as ongoing supervision during and after each TAP session. Importantly, every TAP program is overseen by the TAP founder, a registered art therapist, to ensure adherence to professional and ethical standards. While TAP is strictly non-interventionist and not clinical in nature, the presence and oversight of a registered art therapist ensures that if a participant’s clinical needs arise, these are promptly identified and referred to qualified professionals, upholding standards of care and ethics.

Just beyond the scope of this paper is an exploration of the prospects and ethical considerations of reciprocity from artworking in the TAP space via exhibiting artworks created by TAP. Strict ethical frameworks, critical risk assessments, and curation by the TAP facilitator are called on to be able to move process work into a public space safely and productively. This leads to considerations of how TAP participants and children are artists, and what community art can learn from very young artists and from process art.

Conclusion

There are many ways to embed creativity, visual arts, well-being, and learning within pedagogy. This article has illuminated one such approach through TAP, a program with interwoven research-informed practices at the intersection of art therapy, education, and the visual arts. Run from 2020 and researched in 2023, TAP provides educational settings with vital creative spaces aimed at the development of more complex and abiding learning dispositions and strategies for well-being. TAP’s relational philosophy, principles, and practices provide educational settings with bespoke frameworks that nonetheless remain responsive to specific pedagogies. These frameworks offer creative spaces for artworking, a practice informed by new-materialist perspectives, positioning both human and non-human elements as dynamic agents in the creative process. The program’s adaptive framework supports its efficacy across a variety of educational settings, celebrating diversity, connection, embodied learning, and reflexivity as core elements of the educational experience.

In educational and therapeutic settings, TAP offers a distinctive approach. TAP’s value and vitality derive from its adaptability and relationality. For many educational settings, orientated to standardised procedures and outcomes, TAP provides participants with spaces of agency, allowing for authentic, intrinsically motivated creative engagement.

Beyond the scope of this article are the implications and impacts of reciprocity from artworking with a diversity of people in a diversity of ways. Equipping and trusting very young artists with the respect, rights, and responsibilities associated with artworking in a rapidly changing world may offer unique insights and problem-solving opportunities. TAP is an opportunity for children to add their perspectives to meeting ongoing challenges – they may even make it fun. We just need to create spaces that let them.

References

Armstrong, V.G., & Ross, J. (2020). The evidence base for art therapy with parent and infant dyads: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(3), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1724165

Arnott, L., & Duncan, P. (2019). Exploring the pedagogic culture of creative play in early childhood education. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17(4), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X19867370

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

Barblett, L., Cartmel, J., Hadley, F., Harrison, L.J., Irvine, S., Bobongie, H., & Lavina, L. (2021). National Quality Framework approved learning frameworks update: Literature review. Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority.

Bowlby, J. (1997). Attachment and loss. Volume 1: Attachment. Pimlico.

Buley, J., Buley, D., & Collister, R.C. (Eds.). (2016). The art of noticing deeply: Commentaries on teaching, learning and mindfulness. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-4438-9788-4

Cahill, H. (2015). Rethinking role-play for health and wellbeing: Creating a pedagogy of possibility. In K. Wright & J. McLeod (Eds.), Rethinking youth wellbeing: Critical perspectives (pp.127–142). Springer.

Case, C., Dalley, T., & Reddick, D. (2022). The handbook of art therapy. Taylor & Francis Group.

Cipriano, C., Strambler, M.J., Naples, L.H., Ha, C., Kirk, M., Wood, M., Sehgal, K., Ahmad, E., McCarthy, M.F., & Durlak, J.A. (2023). The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: A contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Development, 94(5), 1181–1204. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13968

Chilton, G. (2013). Art therapy and flow: A review of the literature and applications. Art Therapy, 30(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2013.787211

Cole, D.R. (2013). Lost in data space: Using nomadic analysis to perform social science. In R. Coleman & J. Ringrose (Eds.), Deleuze and research methodologies (pp.219–237). Edinburgh University Press

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic Books.

Deboys, R., Wright, K., & Holttum, S.E. (2016). Processes of change in school-based art therapy with children: A systematic qualitative study. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2016.1262882

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). Athlone.

Department of Education. (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0).

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Capricorn Books.

Fox, N.J., & Alldred, P. (2014). New materialist social inquiry: Designs, methods and the research-assemblage. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(4), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.921458

Franck, L., Midford, R., Cahill, H., Buergelt, P.T., Robinson, G., Leckning, B., & Paton, D. (2020). Enhancing social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal boarding students: Evaluation of a social and emotional learning pilot program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030771

Fraser, D., Price, G., & Henderson, C. (2006). Relational pedagogy and the arts. SET: Research Information for Teachers, 1, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0557

Harris, A. (2014). The creative turn. Sense Publishers.

Hill, C.M. (2017). More-than-reflective practice: Becoming a diffractive practitioner. Teacher Learning and Professional Development, 2(1). https://journals.sfu.ca/tlpd/index.php/tlpd/article/view/28

Jarvis, M. (2011). What teachers can learn from the practice of artists. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(2), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2011.01694.x

Jefferson, M., & Anderson, M. (2017). Transforming schools: Creativity, critical reflection, communication, collaboration. Bloomsbury.

King, J.L. (2025, April 30). Art therapy and neuroscience: The basics with A/Prof. Juliet King [Webinar]. Australia and New Zealand and Asian Creative Art Therapy Association. https://anzacata.org/about

Learmonth, M. (1994). Witness and witnessing in art therapy. Inscape, 1, 19–22.

Lenz Taguchi, H. (2009). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education: Introducing an intra-active pedagogy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203872956

MacAlpine, K. (2021). Common worlding pedagogies in early childhood education: Storying situated processes for living and learning in ecologically precarious times [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Western Ontario]. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. https://core.ac.uk/download/481531383.pdf

Malchiodi, C.A. (2020). Trauma and expressive arts therapy: Brain, body, and imagination in the healing process. Guilford Publications.

Matapo, J., & Roder, J. (2018). Affective pedagogy, affective research, affect and becoming arts-based-education-research(er). In L. Knight & A. Lasczik Cutcher (Eds.), Arts-research-education: Studies in arts-based educational research (pp.185–202). Springer.

Meyerowitz-Katz, J., & Reddick, D. (2017). Art therapy in the early years: Therapeutic interventions with infants, toddlers, and their families. Routledge.

Moula, Z. (2020). A systematic review of the effectiveness of art therapy delivered in school-based settings to children aged 5–12 years. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(2), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1751219

Noddings, N. (2005). What does it mean to educate the whole child? Educational Leadership, 63(1), 8–13. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234595964_What_Does_It_Mean_to_Educate_the_Whole_Child

Palmer, A. (2011). “How many sums can I do”? Performative strategies and diffractive thinking as methodological tools for rethinking mathematical subjectivity. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 1(1), 3–18. https://doi.org. 10.7577/rerm.173

Pascal, C., Bertram, T., & Rouse, L. (2019). Getting it right in the Early Years Foundation Stage: A review of the evidence. Centre for Research in Early Childhood.

Piaget, J. (1953). The origins of intelligence in the child (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Proulx, L. (2002). Strengthening ties, parent-child-dyad: Group art therapy with toddlers and parents. American Journal of Art Therapy, 40(4), 238–258.

Snir, S. (2022). Artmaking in elementary school art therapy: Associations with pre-treatment behavioral problems and therapy outcomes. Children, 9(9), 1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091277

Strang, C.E. (2024). Art therapy and neuroscience: Evidence, limits, and myths. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1484481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1484481

Taylor, A. (2017). Beyond stewardship: Common world pedagogies for the Anthropocene. Environmental Education Research, 23(10), 1448–1461.

Van Lith, T., & Voronin, L. (2016). Developing a critically reflexive practice for art therapists using external perceptions of art therapy. Reflective Practice, 17(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2016.1146580

Waller, D. (2006). Art therapy for children: How it leads to change. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 11, 271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104506061419

Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Playing and reality. Tavistock Publications.

World Health Organization. (2014). World health statistics 2014. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240692671

Author

Georgia Freebody

MArtTher, MRes, GradDipEd, BFA

Georgia is the founder and facilitator of the Therapeutic Art Play (TAP) program, a research-informed initiative situated at the intersection of art therapy, education, and the visual arts. An artist, teacher, art therapist, and researcher, she lectures and workshops visual arts in education at the University of Sydney. Her ongoing art practice is integral to her scholarship, underpinning an arts-informed research praxis that is both relational and interdisciplinary. TAP embodies this praxis, positioning her artworking in educational settings. This artworking cultivates child and material led spaces for connection, becoming, and the development of dispositions supporting learning and well-being. Georgia completed the research that forms the basis of this article as part of higher degree research studies across the disciplines of art therapy and education at Western Sydney University.