Celebrating 20 years. This article appeared in the first issue – ANZJAT, volume 1, number 1, 2006.

Open Access

Published: October 2006

Issue: Vol.1, No.1

Word count: 4,665

About the author

The creative world of children and adolescents with cancer

Diana Hickey

Abstract

Art therapy approaches were used with a group of five young people who were receiving treatment for cancer at Christchurch Hospital. Art therapy aided their negotiation, navigation, communication and the validation of their feelings about the cancer and the medical treatment. The art therapist was considered part of the multidisciplinary treatment team. A qualitative research design was used to observe, record and discuss the progress of these patients and their reactions to the art therapy process. A complementary quantitative measure was used to evaluate anxiety levels before and after each session. The art making process and relationship with the art materials was then facilitated, observed, measured and commented upon.

Keywords

Development, visual art, cancer, therapeutic, paediatrics, acceptance

Cite this articleHickey, D. (2006). The creative world of children and adolescents with cancer. ANZJAT, 1(1). https://www.jocat-online.org/a-06-hickey

Children and cancer

Childhood cancer is common throughout the world. About one in every 600 children develops cancer before the age of fifteen, yet relatively little is known about its causes (Stiller, cited in Plowman, 1992). Cancer is the most common cause of death from disease among children in New Zealand. From the moment children are diagnosed their lives change radically. Leukaemia is the most common type of childhood cancer, representing about one third of all cancers in children under fifteen years old. Children who have cancer may face specific emotional challenges and traumatising events such as the initial diagnosis, their projection of what that means to them and the loneliness and seclusion of being in isolation for protection from infection. They may have fear about their future, confusion about procedures and raised anxiety from the effects of drug therapy (New Zealand Child Cancer Foundation, 2004). Anxiety, depression and instability of self-esteem and body image are widely reported to occur in cancer patients. Anxiety may be further raised due to drug induced confusion and to the continued effects that drug therapy may have on them (e.g. hair loss, painful sores and ulcers, physical impairments and general changes) (Councill, 1993).

Cancer specific stress in children

Santrock (1999, p.269) described stress as “the response of individuals to the circumstances and events (called “stressors”) that threaten them and tax their coping abilities”. Cognitive appraisal is Lazarus’s term for people’s interpretations of events in their lives as harmful, threatening or challenging depending on whether they feel they have the resources to effectively cope with events (cited in Santrock, 1999). Therefore, a patient’s experience of and approach to illness, will largely depend on their already established coping abilities.

Golden (1983; cited in Rode, 1995) identified major sources of stress in children who are ill and hospitalised: separation from the parents or caregivers, relocation to a new environment, the loss of independence and control which accompanies illness and hospitalisation and fears and anxieties about medical procedures which may cause harm or pain.

The most successful means of helping young patients who are in such psychological distress, is by addressing the “negative disorganised feelings and images of the unconscious fight” with the illness, such as separation, loss of independence and control (Prager, 1993). By encouraging children and adolescents to express difficult feelings through art, they may then communicate, recognise and potentially organise them (Councill, 1993; Rode, 1995; Russell, 1995). Expression through art allows the young patient to “accept raw, primary process material and to help externalize and organize it through artistic expression” (Prager, 1993, p.2). Children learn and increase their sense of the world by participating actively and playing out their investigations into reality (Sturges-Nadler 1983). Brunner (1970) explains that by using metaphor to make connections with confrontational issues, the patient may solve problems in a less stressful manner “Metaphor joins dissimilar experiences by finding the image or symbol that unites them at some deeper emotional level of meaning. Its effect depends on its capacity for getting past the literal mode of connecting” (p.63 cited in Sturges-Nadler, 1983).

Sturges-Nadler describes how anxieties of hospitalised children and adolescents that come from fantasy are often much greater than those arising from reality. She makes the point that by making these fantasies tangible, the patient’s medical treatment and emotional care are made easier. She continues that children must be allowed to develop images of fantasy and reality, through safe, structured, supervised art therapy experience to bring out all the elements of their traumatic experience. The child should eventually arrive at a finished externalised form of their experiences through exploration and the introduction of image or object, which can then act as an incentive for dialogue.

Dreifuss (cited in Jeppson, 1982) tells us that the fears and fantasies connected to cancer are unique and are related to particular images. She tells us that, independent of diagnosis, prognosis, course of illness and related therapy, many patients feel defeated by a destructive process for which they have no defence and which appears to destroy them from within. Councill (1993) shows that through rehearsal of troubling events and working out concepts of the self through art expression, children and adolescents can master their feelings and fantasies about their illness and treatment.

Rollins (cited in Councill, 1993) tells us that, while patients come to hospitals primarily for medical treatment, art therapy may be seen as a uniquely humanising influence in the midst of an experience that threatens the child’s sense of self and trust in the world. Art making in hospital environments can bring familiar and mostly enjoyable experiences. The art therapist holds no threat of unwelcome interventions and even offers the choice to participate in the sessions, thereby gaining trust and developing a unique relationship with patients. Councill (1993) proposes that the art therapy session can be one of the few avenues of communication with hospital staff left open when children and young adolescents are overwhelmed by their hospitalised situation. It creates a bridge of communication between patients and medical staff. In this way, art therapy may provide medical staff with new insights into the client’s perception. It may also offer insight to staff as to the degree of anxiety in the patient and opportunities to correct misconceptions if they have arisen. Young patients may also arrive at a level of acceptance of their situation that may not have been accessible in a normal working relationship of patient/ medical staff.

Art therapy in the field of oncology

Paediatric cancer patients may benefit from early psychosocial intervention, including art therapy, based on the principle that the initial diagnosis of cancer and following treatments represent stressors that warrant such interventions (Jeppson, 1983). Art therapy can coexist alongside several other psychosocial programmes to support patients during their hospital experience (Rode, 1995). Tracy Councill (1999) who works as an art therapist and paediatric oncology team member outlines the following as specific goals of art therapy with paediatric cancer patients: inviting emotional expression, encouraging symbolic representation of physical states, developing personal imagery, expressing expectations of treatment outcomes, facilitating coping through diversion and finally building a sense of competence and control.

Robert Rice (cited in Jeppson, 1983) provided art therapy activities for cancer patients and their families to reinforce their self-belief and re-establish their self-esteem. Art therapy also offers a bridge between present understanding and future possibilities of insight (Jeppson, 1983). By offering activities to cancer patients through an art therapy programme in hospital waiting rooms, Jeppson outlined three ways with which the patients used the art, therapy experiences: some sought to stay busy, because the waiting increased their anxiety (diversion), some sought to relieve their pain (distraction) and some discovered new skills, which could be further pursued at home (resilience) (Jeppson 1983).

Purpose of research

The rationale of the research reported here, was to implement a visual arts programme with children and adolescents in a hospital setting so that the researcher could:

Measure the reduction of levels of anxiety and discomfort in young oncology patients using art therapy during their treatment while either at hospital or as outpatients

Explore their feelings about their illness and circumstances during this time.

Examine the benefits of this Visual Art Programme for both the patients and medical staff.

The researcher’s main responsibility during these sessions was to facilitate the art programme from a humanistic, client-centred perspectives encouraging spontaneous art expression and offering technical art guidance where required by participants. It was also to provide pre- and post-test questionnaires and to observe the responses of the participants to their art process and art product. The close proximity of the researcher to participants during individual sessions allowed for direct study. However, this disclosed observational role and the requirement of filling out a questionnaire pre- and post-session may have had an I effect on some participants’ initial approaches to art making, for example, this may have inhibited their natural creative expression.

Participants

Patients were primarily identified by their medical diagnosis of cancer, their ages and their attendance at Christchurch Hospital. The overall recruitment of participants was at the discretion of the medical staff, with health state as the main criteria. Oncology patients were chosen as a population to research as the length, frequency and discomfort levels were all higher than with other child patient populations. There were no ethnic or cultural restrictions on the population of participants, nor was their socioeconomic status taken into account. All participants available at the time of the study were Pakeha or non-Māori descent.

As the participants had been diagnosed with varying forms of cancer prior to their hospital stay they were all receiving chemotherapy. They were all at different stages of their treatments. Participants were chosen between the ages of eight and nineteen years of age because of their level of cognitive development and coordination skills. Amy was a sixteen-year-old female with newly diagnosed bone cancer from out of the region.

Amy was very upset at her changing body image as she had a goal of being a model. Her social lite was more important to her than her medical treatment.

Missy was a ten-year-old female diagnosed with leukaemia; she was also from out of the region. Missy was initially a very shy girl who did not readily express emotion, was physically tense and often held her breath, She liked privacy and hated being the centre of attention which her medical condition often required.

Karen was nineteen and in the middle of her treatment for bone cancer; her mother remained with her as a companion as they lived out of the region. Prior to her diagnosis Karen had been a successful athlete. The bone cancer had seriously disrupted this life path. While she never discussed her illness, she never appeared daunted by any of her circumstances.

Gwen was a sixteen-year-old female diagnosed with leukaemia; she was nearing the end of her treatment. She went home before the last session. Her mother cared for her whilst living at Ronald McDonald house as they lived out of the region. Her mother’s sight had begun to fail and so the pair was reliant on each other.

For the purposes of this article, I will highlight one case study.

John was a fourteen-year-old male diagnosed with leukaemia. He was nearing the end of his chemotherapy treatments and was in air-locked isolation for the duration of his five sessions in the bone marrow unit. He was from Christchurch and had both parents caring for him. John was released before his final session. He was an intelligent jovial boy with a very sharp wit, had a passion for motorbikes and was a keen motorcyclist before his diagnosis. John struggled with his confinement in isolation. He was always interested in his temperature, blood count and neutrophil levels (immune system) as they indicated his physical state and therefore his potential release from hospital. John was also aware of bodily changes such as heart palpitations, anaphylactic shock symptoms and numbness as these had been the early warning signs for some of his health crises in the past.

Research methods

As many variables were involved in properly exploring the above issues raised for this enquiry, three methods of research were used:

The quantitative measurement of anxiety with the pre- and post-STAIC questionnaires or the “State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children”.

Qualitative journaling for case studies by the researcher after each session in the role of art therapist as an observer.

Collecting images of art works produced by participants was also important to visually support the findings.

Quantitative research

The quantitative element of this research was the STAIC or the ‘State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children”. The STAIC is useful in situations where a swift, routine assessment of a child or adolescent’s problems is required with minimum impact. It assesses the major dimensions of anxiety in young persons from the ages of 8+ years and is administered by self-report. This measure is currently used by hospital staff and so provided a recognised and credible measure in this setting.

The STAIC measure consists of two scales. The A-State (C1) scale consists of twenty statements that ask children how they feel at a particular moment in time. It measures transitory anxiety states, that is, subjective, consciously perceived feelings of apprehension, tension and worry that vary in intensity and fluctuate over time. The A-Trait (C2) scale consists of twenty statements that ask children how they generally feel. It measures relatively stable individual differences in anxiety proneness, that is, differences between children in the tendency to experience anxiety states (Platzek, 1973).

The STAIC questionnaire was administered at the beginning and end of each session. Prior to the first session, the participant was asked to fill out STAIC questionnaires; C1 and C2. At the end of the session, the participant was asked to complete only C1. For subsequent sessions, the participant was only asked to fill out the questionnaire C1 before and after each session. This was normally completed in three to five minutes. Each questionnaire was then added to score between 20 (lowest anxiety level) and 60 (highest anxiety level).The results were then transferred to a profile form which was kept in a secure file along with case study notes pertaining to the individual participant.

Calculating results

A dependant sample “t-Test” was used to quantify the results as the pre and post scores were from the same person and therefore related to each other. This method was used to examine the differences between one group of participants, on one or more variables and to compare if there was a significant difference between the means of the variables studied. Using a quantitative method allowed a degree of objectivity and a means of substantiating any qualitative findings (Gantt & Goodman, 1997). It is the duty of artists working within therapeutic situations to articulate as fluently as possible in order to communicate with as well as understand the medical/ helping professions (Moon, 1997; Rode 1995).

Quantitative results

Data was collected from the participants through 28 sessions over a six-month period. Three participants attended all six sessions. The remaining two were discharged from the hospital after the fifth session as their treatment had ended.

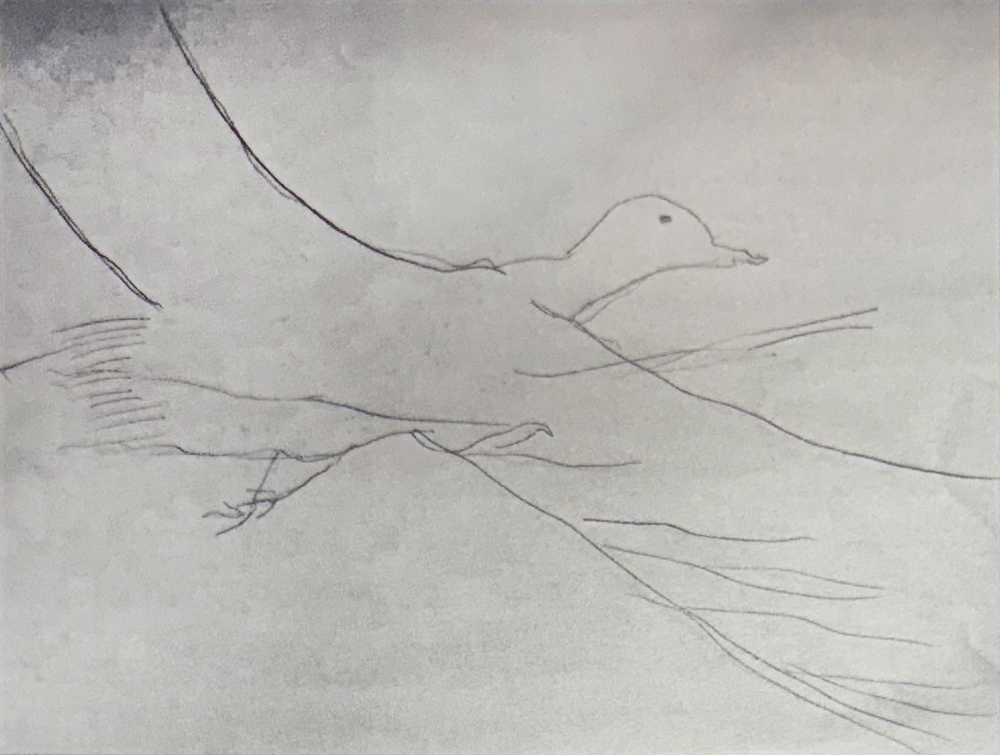

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

Table 4. Pre- and post-test levels of anxiety of all participants.

Table 1 shows the raw data generated by the sessions. In the first column highlighted, is the name of the participant and under that is their Trait score, (How-I-feel usually) , which was only taken once at the beginning of the first session. This Trait score was then used as a comparative measure of the participants’ general level of anxiety. In the second column are the session numbers, the State score, (How-I-Feel at this very moment) pre-test and post-test scores are in the third and fourth columns.

Table 2 shows average pre- and post-test State scores. The averages of all participants post-test were lower than pre-test scores. This is also shown in the group total (seen on bottom line 29.6/27.8). This indicates an average decline in anxiety by 12% during each session. The largest average drop in anxiety was 23.5% and the lowest was 0.7%.

Table 3 shows the statistical analysis of pre and post-test score differences. The highest post-test drop in anxiety in a single session was 17.0 and the lowest was -2.0. The standard deviation was 4.35 and the t-value was -4.2. The average pre /post state measure drop in anxiety was 3.5. The two-tailed P value equals 0.0003, considered highly statistically significant.

In Table 4 the quantitative data generated by the STAIC, is converted into a line chart to illustrate the pre- and post-test effect of art therapy sessions on participants· changing anxiety levels together over the duration of sessions.

Qualitative research

In art therapy situations there are continually changing results dependent on children’s responses to varied mediums, their level of recovery and their different personalities Two sets of questions were applied to the qualitative data collected through the art therapy sessions ,n order to organise observations and review participants’ responses (Malchiodi, 1998). One set were process related, the other product related. This information was then reported individually as each participant’s phenomena.

Collecting images of art works

Retaining visual records of the patients’ art works offered a platform to discuss individuals’ use of the art therapy process. It also allowed diagrammatic evidence to speak about the patients’ emergence of meaning. This was approached through narrative analysis, which examined how information was organised and presented by the patient/participant, in the form of their resulting art pieces. While interpretation was generally left to the patients themselves in this investigation, some symbolic meanings and image themes were compared to previous images generated through art therapy studies with young cancer patients. Through a comparative summary, visual themes offered another means of analysing the qualitative and quantitative data but were not used for diagnostic purposes.

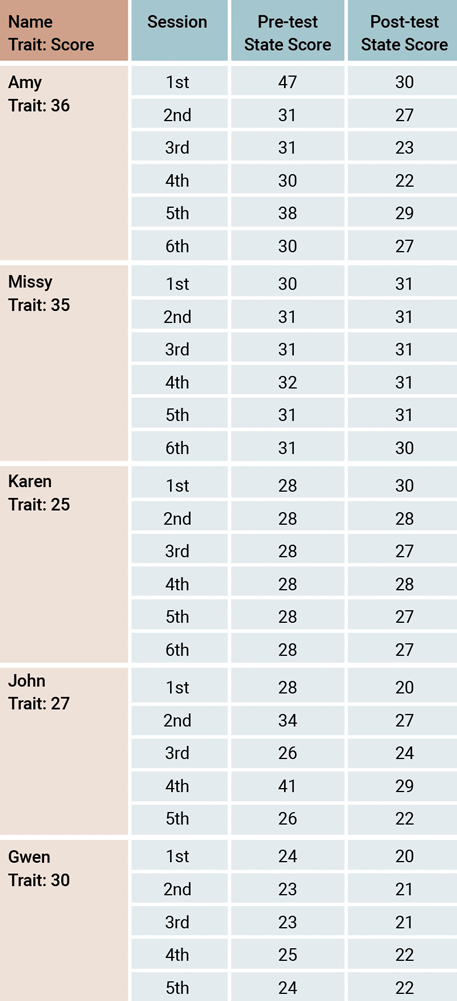

John used his art making as a form of diversion and escapism. In his first session, he drew a picture of his dream island snorkelling trip to Fijian Island, talking of how it would be quiet with his head under the water and how clear and calm the sea would be. He talked of lying in a hammock slung between the two trees (centre) but later decided that the island looked nicer unpopulated. Taking into account John’s sense of intrusion and confinement , it may be that the vacant island was reflecting his need to seek refuge, however by deciding that it looked better uninhabited, it may have paralleled his feelings of displacement and isolation; the vast expanse of sea also suggests that he was exploring a sense of freedom. John exclaimed that the sea was a little rougher than he had expected, “like my hospital stay”, reflecting his feelings in a safe manner and suggesting that he might see himself as the island. The encroaching waves that he has cut into the paper suggest a sense of an impending untimely conclusion.

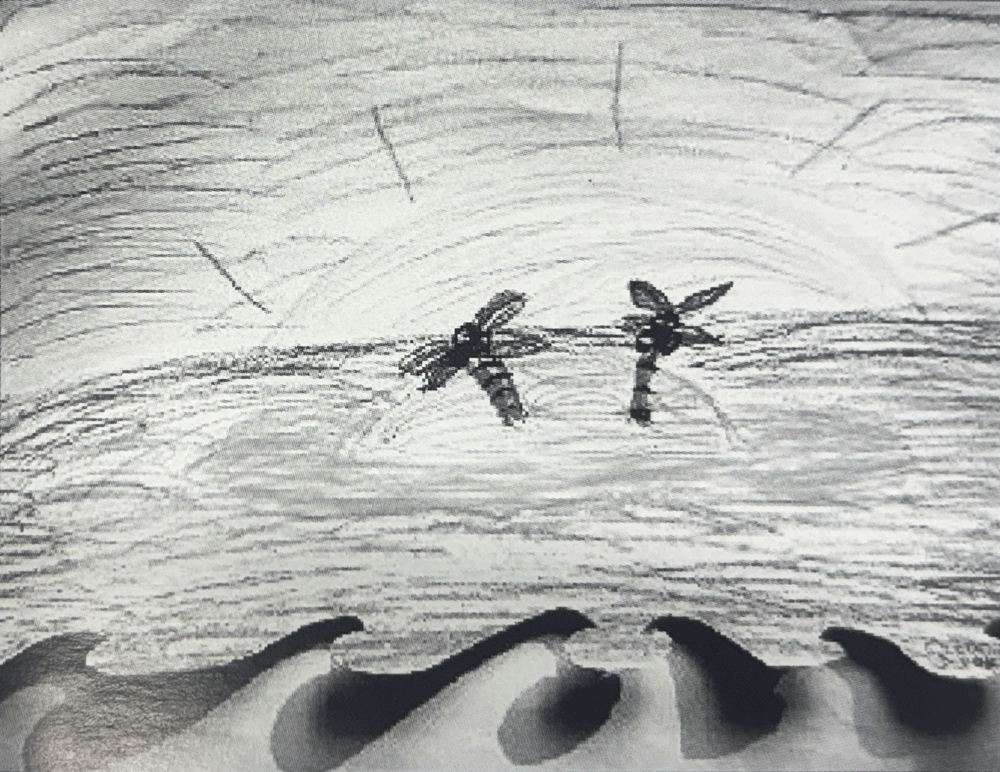

In his third session, John was very excited as he was close to being discharged but his neutrophil points (that gauge immune system levels) remained static for several days. Through exploring what he would do with his elusive freedom, he chose to draw a motorbike, thereby addressing his pent up frustration. He solved technical problems, his breathing began to deepen and he gradually became focused rather than distracted, suggesting that the engagement in artwork calmed him considerably. When finished, John appeared to have a renewed sense of commitment to his treatment and its outcome. He seemed to use the offered art making process as a rewarding and engaging activity that transported him from his difficult surroundings to a place of achievement and satisfaction, giving him a renewed sense of determination.

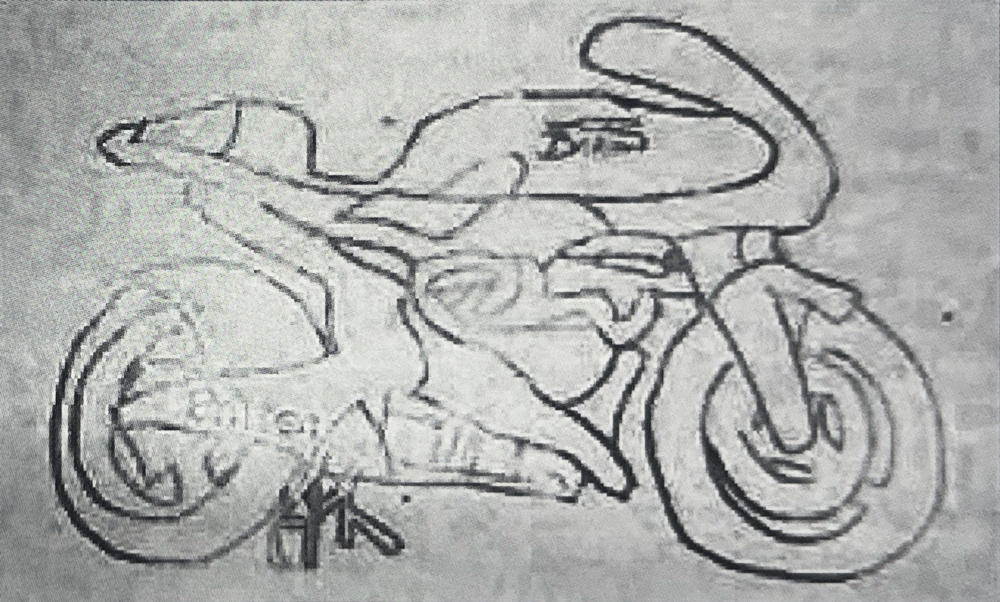

Another form of expression was seen when John drew his “Black bird” a symbol representative of the darker side of a person’s nature (Bach, 1990), during a particularly challenging time. He was confused by a combination of feelings of anger, isolation, fear, frustration and disappointment and was exhausted. He sketched the bird confidently, talking of the colours he would make it. However the colours never appeared and instead John talked of confinement, bad dreams and praying. John commented that colour seemed out of place on his bird, that 1t was better left black. He had seemingly touched on his unexpressed fears, questions and anxieties about death through his art work that he found too real to tackle directly this may have a bearing on wt1y tie chose not to finish the image.

Discussion

The findings supported the hypothesis, that the effects of a visual arts programme, offered in a therapeutic way, would have a beneficial impact on young patients with cancer. This is supported by both qualitative and quantitative indicators

The participants’ anxiety levels, as measured by the STAIC indicated that as a whole the group experienced a statistically significant reduction in overall anxiety following art interventions in comparing the pre and post-test scores over the course of the sessions. However as the size of the sample was small it is equitable to look at individual results as well. Of a sample of five, three had significant consistent reductions in their anxiety levels and two showed marginal reductions.

A number of observations can be made about the test scores taken from individual perspectives.

Patients who seemed verbally expressive about their illness appeared to have greater fluctuations in their anxiety levels, while those who spoke less about their illness and its effects had fewer fluctuations in test scores.

The reductions in anxiety levels, as shown by the test scores, appeared to relate to the participant’s ability to express him or herself visually.

Other factors affecting ability to be verbally expressive appeared to be developmental stage and the stage of illness and treatment. Individual’s existing personal coping styles may also have had an impact on their art making.

While it is impossible to assume definite conclusions about the data provided due to the small size of the sample, it is apparent here that the more expressive participants were about their illness, the more their anxiety levels appeared to drop during their sessions.

Patients’ beneficial use of the art sessions I resulting in their reduced anxiety, which was dependent on their ability to express openly, can also be examined by looking at participants individual final scores. Missy finished with the highest post-test score of 30. Of all participants, she seemed overall the least openly expressive, she was in the middle stage of her treatments and may have used her detachment as a form of coping. Amy and Karen were next on 27; as Karen’s sessions progressed, her expression developed and she came to terms with her situation more fully. Amy was communicative throughout her sessions and made much progress on her overall acceptance of her circumstances through her art sessions, however, if her progress were to be followed through to the conclusion of her treatments, she too might begin to censor her expression in an attempt to apply some control over her circumstances. Finally, John and Gwen each finished on 22. John’s levels had greater variation in his general scores but his eventual level indicated that he was less anxious than at the end of any other session. Gwen’s lower score in anxiety was consistent throughout her art therapy sessions. Overall, the findings of the STAIC provided data that supports the hypothesis that a visual arts programme can offer a reduction in overall anxiety experienced by young cancer patients. However, it is clear that the measurement did not always pick up subtle yet significant changes in participants’ feelings alone, nor did it highlight the issues that caused them distress.

Conclusion

Through the qualitative documentation of the art process, participants’ experiences were illustrated to show their methods of coping using art process and product as a means of diversion and escapism and re-establishing a sense of competence and control. These tools were also shown as potentially valuable in reinforcing their self-belief and self-esteem, which may suffer in dealing with cancer and its many challenges Participants used art sessions for self-expression, self-definition and mastering skills. Art making also gave them an opportunity to practice decision making and accomplish problem-solving, continuing their development as children and adolescents.

The research supports previous findings where art therapy has enabled the participants’ exploration, understanding and acceptance of themselves and their circumstances and their sense of self- fulfilment. The art sessions have provided opportunities for participants to maintain a reasonable emotional balance, to re-create an acceptable self-image and offered some the opportunity to prepare for an uncertain future by addressing their fears of death.

While the art making process and product offered instant satisfaction and gratification to the participant as well as coping tools for the future, the study has confirmed that it has also helped to preserve relationships with friends and family and medical staff when communication had become strained. The opportunity to communicate fears without burdening loved ones eased the strain on close relationships, as participants could retain much needed independence and feel like less of a responsibility and parents got opportunities for rest and self-care returning to see their children lighten and apparently feeling more capable. Through feedback from the art therapy sessions, medical staff gained further understanding about their patients’ phenomenology and ability to cope, aiding them in making more informed decisions about their patients overall care and enhancing communication channels.

Limitations of the study

While the specific findings reported on individuals were informative, the sample was small. Furthermore, a multidimensional anxiety scale might give more in-depth results with participants of these ages. Alternatively, a combined test for depression and anxiety might give a more accurate view of participants’ emotional and psychological states pre and post- art therapy sessions. Having an independent observer or facilitator might also be an asset, as the multi-functional role of researcher, facilitator, observer and student was difficult to conduct concurrently and while the researcher endeavoured to check bias at all times it was still potentially possible as she had a vested interest in all aspects of the outcomes .

The period over which participants were examined was short and did not follow the full treatment process for any of the participants. Rode (1995) raises the point that art therapists endeavour to align with the patient to “observe the illness and to devote time and space to allow it to tell its story” (p.109). By following the treatment from diagnosis to eventual discharge back home, an inclusive examination might give more insight for art therapy approaches in cancer specific paediatric populations. Conducting structured interviews with participants’ caregivers both medical and familial might offer more information about the perceived challenges for all involved.

Implications for further research

A larger sample size is needed if this study is to be reapplied to other paediatric oncology situations to confirm or refute the findings. Art therapy sessions could be offered from diagnosis to the end of treatment to give a more in-depth and accurate account of the enquiry. The implications from findings in this study suggest that young patients with cancer have a developmental process within their illness at the different stages that they experience which affects their means of expression. One hypothesis potentially worth testing is whether art therapy approaches can be defined to address patients’ needs and support their development of coping strategies as they go through these different stages of treatment and illness. This could be approached by studying the beneficial effects of art therapy sessions, with a special focus on participants’ stages of treatment and developmental progress, further exploring and improving methods of communication through art therapy for patients at these stages of treatment and illness.

Implications for practice

This study has suggested how art therapy can offer positive diversion and enhanced means of coping, through expression, exploration, understanding and acceptance of circumstances for young patients with cancer in hospitals. While it is idyllic to hope that every oncology unit might employ an art therapist who could work alongside young people in these circumstances, medical staff and caregivers might perhaps support patients to use art activities as expression, diversion and esteem-building, thus encouraging their growth and development and preserving their normalcy. Furthermore, staff and parents alike might demonstrate increased respect of patients’ privacy and personal boundaries, in order to aid them in developing their sense of independence, self-direction, choice and control. Medical staff could further consider the complex methods of coping that patients construct in order to endure their distressing circumstances thereby minimising the issues associated with their illness and hospitalisation. Beyond the paediatric oncology setting, these suggestions may also be applied to other hospitalised child populations or children in stressful or traumatising circumstances, which may disrupt that developmental process.

Most importantly, offering young people with cancer opportunities to be creative through visual art, may equip them with a simple, yet effective, constructive personal resource. Providing them with an active role in their process of recovery and acceptance is a precious contribution in itself.

References

Agell, G, & Williams, K.J. (1996). Art-based diagnosis: Fact or fantasy? American Journal of Art Therapy, 35(1), p.9.

American Art Therapy Association Inc. (2004). Retrieved 14th May, 2004. Available: http://www.arttherapy.org/ aboutarttherapy/faqs.htm

Bach, S. (1990). Life paints its own span. Einsieden, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag.

Councill, T. (1993). Art therapy with pediatric patients: Helping normal children cope with abnormal circumstances. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Therapy Association, 10(2), 78–87.

Councill T. (1999). In C. Malchiodi, (Ed.), Medical art therapy with children. London, England and Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Gaezer-Grossman, F. (1981). Creativity as a means of coping vvith anxiety. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 8, 185–192.

Gantt, L. & Goodman, R. (1997). Research. American Journal of Art Therapy, 36(2), 31.

Golden D.B. (1983). Play therapy for hospitalized chilren. In D.C. Rode, Building bridges within the culture of pediatric medicine: The interface of art therapy and child life programming. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 104–110.

Goodman, R.F. (1996). Cited in Agel I.G, & Williams, K.J. (1996) Art based diagnosis: Fact or fantasy? American Journal of Art Therapy, 35(1), 9.

Jeppson, P. (1982). Creative approaches to coping with Cancer: Art and the cancer patient. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Conference of the American Art Therapy Association, 45–47.

Malchiodi, C. (1998). Understanding children’s drawings. New York: The Guilford Press.

Moon, C. (1997). Art therapy: Creating the space we live in. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 24(1), 45–49.

Paired t-test. (2004). Calculation page. Retrieved 28th May, 2004, from http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/ Paired t-test NROW form.html

Platzek, D. (1973). STAIC preliminary manual. US: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.

Prager, A. (1993). The art role in working with hospitalized children. American Journal of Art Therapy, 32(1), 2.

Prager, A. (1995). Pediatric art therapy: Strategies and applications. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12(1), 332–38.

Rode, D.C. (1995). Building bridges within the culture of pediatric medicine: the interface of art therapy and child life programming. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12(2), 104–110.

Rollins, J.H. (1990). Helping children cope with hospitalization. Imprint, 37(4), 79–83.

Russell, J. (1995). Art therapy on a hospital burn unit: A step towards healing and recovery: Sacramento, CA. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12(1), 39–45.

Santrock, J. (2002). Lifespan development (8th Ed.). Dallas: McGraw Hill.

Stiller C.A. (1992). Etiology and epidemiology. Available: http://www.cancerindex.org/ccw/guide2c.htm. Retrieved May 10, 2004.

Sturges-Nadler, H. (Spring, 1983). Art experience and hospitalized children. Care of HG, 11(4).

Author

Diana Hickey

MA ATh Hons

Irish born and a New Zealand citizen, Diana is employed as an art therapist and researcher at Christchurch Public Hospital. She works in Paediatrics with the pain team with children who suffer trauma and chronic illness including children who have cancer and their families.