Open Access

Published: July 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-4.0

Issue: Vol.20, No.1

Word count: 1,895

About the reviewer

Exhibition review

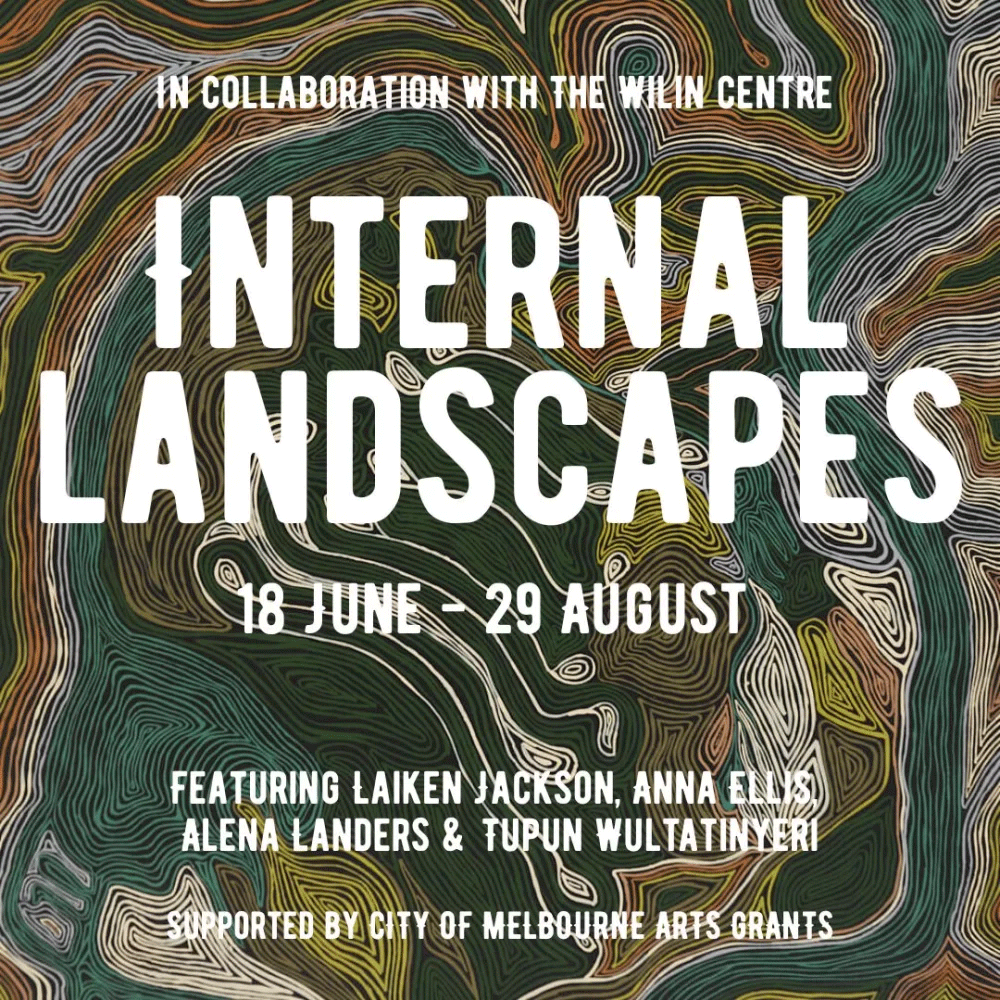

Internal Landscapes

Held at the Dax Centre, Melbourne

Artists: Laiken Jackson, Anna Ellis, Alena Landers and Tupun Wultatinyeri

18 June – 29 August 2025

Reviewed by Georgia Ruby Polichroniadis

Acknowledgement of Country

I write this reflection from the lands now known as Merri-bek, on the unceded Country of the Wurundjeri Woi-Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation. I acknowledge their enduring sovereignty and deep connection to land, water, and community. I pay my respects to Elders past and present, and extend this respect to the First Nations artists whose works are the focus of this review. I recognise the diverse and profound Indigenous ways of knowing, being, creating, and healing – many of which I have learned through conversations with the artists of Internal Landscapes. I offer my heartfelt thanks to them and affirm that sovereignty was never ceded; it always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Cite this reviewPolichroniadis, G.R. (2025). Exhibition review: Internal landscapes. JoCAT, 20(1). https://www.jocat-online.org/r-25-polichroniadis-2

Figure 1. Artists Anna Ellis, Laiken Jackson, Tupin Wultatinyeri, and Alena Landers, Internal Landscapes, 2025. Photograph courtesy of The Dax Centre.

Affective landscapes: Art, trauma, and cultural continuity

Internal Landscapes, exhibited at The Dax Centre and co-curated with the University of Melbourne’s Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development, marks a significant intervention into how trauma, healing, and culture can be represented and held in artistic form. Through the works of four First Nations emerging artists, Alena Landers, Anna Ellis, Laiken Jackson, and Tupun Wultatinyeri, the exhibition explores not just internal states of psychological distress, but broader histories of survival, cultural continuity, and transformation.

Drawing on affect theory (Gregg & Seigworth, 2010; Massumi, 2002), the exhibition can be understood as an affective landscape: a spatial and sensory terrain where viewers encounter emotional residues, histories of displacement, and the embodied presence of culture. The gallery becomes a liminal site between institution and community, between aesthetic contemplation and deep listening, where the affective charge of the works is not interpreted through conventional curatorial texts but instead mediated through texture, repetition, silence, and gesture.

Each artist contributes a unique affective vocabulary. Jackson’s performance work fragments time and narrative, evoking the disorientation and spectrality of intergenerational trauma. Wultatinyeri’s topographical forms, marked by gestural layering and cartographic abstraction, speak to a deep intimacy with Country, offering viewers a visual syntax of place that is at once personal and collective. Ellis’s tactile fibre-based works use felting techniques to evoke softness, slowness, and repair, processes associated with nervous system regulation and neurophysiological healing. Meanwhile, Landers’ paper works reflect delicate processes of endurance and repetition, inviting associations with ritual, mourning, and quiet resistance.

These works enact what Clough (2007) refers to as affective memory: pre-verbal, bodily inscriptions that precede language but are nonetheless saturated with meaning. This is of particular relevance to art therapy, where non-verbal expression can offer pathways to emotional integration that elude talk-based modalities. Internal Landscapes thus offers not only an exhibition, but a proposition: that affect itself is knowledge – felt, relational, and somatically inscribed – and that trauma must be addressed within cultural frameworks of continuity and resistance.

Figure 2. Installation view of Discarded, Every Last Scrap, 2025, and Loose Fragments, 2025, by Alena Landers; eco-paper production, wooden rods and wool, dimensions variable. Photograph courtesy of The Dax Centre.

The Dax Centre and the Wilin Centre: Platforms for healing and storytelling

The collaboration between The Dax Centre and the Wilin Centre underpins the curatorial and therapeutic integrity of Internal Landscapes. The Dax Centre, with its long-standing history of championing mental health awareness through art, brings institutional credibility and a vast collection grounded in the lived experience of psychological distress. Its mission to reduce stigma and provide avenues for education through art aligns with the exhibition’s implicit challenge to pathologising discourses in mental health.

However, what makes this collaboration exceptional is the involvement of the Wilin Centre, which positions cultural sovereignty at the heart of artistic practice. By centring Indigenous-led curatorship and culturally specific knowledge systems, the Wilin Centre ensures that the exhibition is not merely inclusive, but structurally anti-colonial in its framing. This partnership offers a powerful model for trauma-informed arts programming that resists tokenism and instead enacts deep cultural collaboration.

Together, these institutions function as platforms for healing and storytelling. They foreground the importance of culturally safe spaces and refuse the often-extractive logic of Western institutions. Their work exemplifies the need for reciprocal partnerships where Indigenous voices guide and shape how trauma, culture, and resilience are represented and understood. For those in the creative arts therapies, this collaborative model offers a roadmap for ethical engagement with communities and institutions in ways that honour sovereignty and lived experience.

First Nations perspectives on trauma-informed care

Trauma-informed care, as it is typically understood in Western clinical contexts, often prioritises individualised approaches, focusing on symptom management, safety, and client autonomy. While these principles are valuable, they can inadvertently reinforce a biomedical framework that isolates trauma from its sociohistorical and cultural roots. Internal Landscapes foregrounds a different paradigm: one where trauma is understood as relational, collective, and embedded in both historical injustice and cultural survival. Through the lens of First Nations epistemologies, trauma is not merely an internal wound, it is a consequence of colonisation, systemic violence, and the attempted disruption of cultural continuities. The exhibition aligns with Indigenous trauma theories that understand healing as a holistic, communal, and spiritual process (Atkinson, 2002; Dudgeon et al., 2014). In this paradigm, trauma-informed care must encompass Country, community, kinship, and ceremony.

The non-linear, process-oriented format of the exhibition reflects these values. It resists closure, opting instead for gestures of presence, listening, and relationality. This is evocative of dadirri, the Ngan‘gikurunggurr concept of deep listening and quiet awareness (Ungunmerr-Baumann, 2002). Within the exhibition, dadirri is not only a conceptual underpinning, but a curatorial strategy, one that invites viewers to slow down, to attend, and to sit with discomfort. This is not a passive stance, but a political and ethical orientation that affirms the integrity of cultural knowledges and healing practices.

Figure 3. Installation view of Where My Miwi is Strong #1 and Where My Miwi is Strong #2, 2025, by Tupun Wultatinyeri; acrylic on canvas, 880 × 800mm. Photograph courtesy of The Dax Centre.

Art therapy and art as therapy: A necessary reconsideration

The longstanding tension between ‘art therapy’ as a formal, clinical intervention and ‘art as therapy’ as a spontaneous, autonomous act of healing is brought into sharp relief in Internal Landscapes. These works are not produced within a traditional therapeutic alliance, yet they enact therapeutic processes through their very existence, materiality, and reception. In much of Western clinical training, the distinction between art created within therapy and art created as therapy is upheld in order to preserve ethical boundaries and treatment integrity. However, this binary can inadvertently reproduce hierarchies that devalue community-based, culturally embedded, and artist-led practices of healing. In Indigenous contexts, such separations may not exist at all. Art is not an ‘intervention’; it is life, story, and relationship.

McNiff (2004) challenges us to reconsider where and how healing happens, suggesting that the expressive act itself is often more vital than its interpretation. Internal Landscapes supports this claim. The art here is affectively potent, relationally driven, and spiritually grounded. It resists objectification and diagnosis, instead offering portals into lived experience, resilience, and cultural endurance. This calls on art therapists to re-evaluate our frameworks: to interrogate where we place authority, how we define healing, and what forms of knowledge we privilege. It reminds us that art therapy must remain open to other ways of knowing and being, particularly those shaped by Indigenous cosmologies, storytelling practices, and collective histories.

Embodied witnessing and the power of art

One of the most profound contributions of Internal Landscapes lies in its invitation to the viewer not simply to see, but to feel and become an embodied witness. The exhibition disrupts the conventions of detached spectatorship that often define gallery spaces. Instead, it cultivates an environment in which the viewer is asked to be present – emotionally, somatically, and relationally – with the artworks, their makers, and the cultural histories they carry. This kind of witnessing goes beyond visual appreciation. It requires that the body participate in the act of reception, that we allow ourselves to be affected. Viewers may notice a quickening of the breath, a tightening of the chest, a softening in the shoulders – bodily responses to the textures, materials, and spatial compositions on display. These visceral reactions are not incidental, they are integral to the exhibition’s structure and therapeutic power. In this way, the exhibition becomes a site of somatic attunement (Frank, 1995), where body and image co-constitute meaning.

In art therapy, the notion of embodied witnessing is increasingly recognised as a vital part of relational practice (Kapitan, 2014). It reflects the therapist’s willingness to be impacted, to co-regulate, and to share in the emotional and symbolic labour of creative expression. The experience of viewing Internal Landscapes evokes this same dynamic. We are not merely encountering works about trauma, we are engaging with trauma as it pulses, breathes, and unfurls in real time through fibre, pigment, gesture, and form.

The curation itself supports this embodied engagement. Works are spaced to encourage quiet contemplation; the absence of excessive wall text removes interpretive scaffolding, inviting felt responses instead. Silence becomes a curatorial strategy – a space in which emotional resonance can expand. In particular, the use of fibre-based and performative media engages the haptic senses, creating an affective feedback loop between artwork and viewer. Ellis’s felted wool evokes tenderness and repair; Landers’ paper forms rustle quietly with impermanence and care. Wultatinyeri’s maps are not inert, they vibrate with songlines. And Jackson’s performance work compels the viewer to hold their breath, to witness without interruption, to feel the rupture of time.

This process echoes what Baz Kershaw (1999) describes as intensified embodiment in performance; moments in which the boundaries between audience and artist dissolve, allowing for mutual vulnerability. In the context of trauma and healing, such moments are potent. They allow the viewer to experience solidarity with the artist, not in the form of voyeurism or consumption, but in a shared encounter with pain, resistance, and transformation. The affective labour required of the viewer is part of what makes Internal Landscapes so ethically resonant. The act of embodied witnessing here is not passive; it is a kind of relational reciprocity, a way of saying, “I see you. I feel with you.” It disrupts the asymmetry of institutional spaces where First Nations knowledge is often extracted or observed from a distance. Instead, it requires that non-Indigenous viewers enter into a process of accountable presence. This, too, is healing work.

In art therapy, we are trained to create spaces where clients can be seen, heard, and held – where art serves as both container and bridge. Internal Landscapes demonstrates how these same principles can operate within public cultural spaces, offering an expanded vision for how we might think about therapeutic witnessing beyond the confines of the studio. The viewer becomes a participant in the process – not to solve or analyse, but to honour, to hold, and to be transformed through contact.

Ultimately, the power of Internal Landscapes lies in its capacity to elicit not only empathy but also a deepened awareness of relational interdependence. As I stood in the gallery, moved to stillness by the delicate fibres of a wool vessel or the haunting trace of a performance, I was reminded that witnessing is not simply about what we see, it is about how we show up, in body and spirit, to what is being offered.

Figure 4. Anna Ellis, And Yet She Loves Them, 2025, wet felted wool (Corriedale), calico and wool yarn, 1700 × 1590mm. Photograph courtesy of The Dax Centre.

Conclusion

Internal Landscapes is a landmark exhibition in its centring of First Nations voices, its commitment to trauma-informed and culturally grounded practices, and its capacity to move beyond representation into resonance. For those in the creative arts therapies, it serves as a compelling call to expand our frameworks, to decolonise our methodologies, and to deepen our commitment to relational, affective, and culturally situated care. This is not merely an exhibition to be seen, it is an experience to be felt, to be held, and to be learned from. I urge art therapists, students, and scholars to engage with it, not only as professionals but as fellow human beings invited into a sacred space of story, survival, and shared presence.

References

Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails, recreating song lines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Spinifex Press.

Clough, P.T. (2007). The affective turn: Theorizing the social. Duke University Press.

Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., & Walker, R. (Eds.). (2014). Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (2nd ed.). Commonwealth of Australia.

Frank, A. (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. University of Chicago Press.

Gregg, M., & Seigworth, G.J. (Eds.). (2010). The affect theory reader. Duke University Press.

Kapitan, L. (2014). Introduction to art therapy research (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Kershaw, B. (1999). The radical in performance: Between Brecht and Baudrillard. Routledge.

Massumi, B. (2002). Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press.

McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Shambhala.

The Dax Centre. (n.d.). https://www.daxcentre.org

The University of Melbourne. (n.d.). Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development. https://finearts-music.unimelb.edu.au/wilin

Ungunmerr-Baumann, M.R. (2002). Dadirri: Inner deep listening and quiet still awareness. In D. Grossman, J. Parker & K. Clunies Ross (Eds.), Blacklines: Contemporary critical writing by Indigenous Australians (pp.117–123). Melbourne University Press.

The Dax Centre is a leader in the use of art to raise awareness and reduce stigma towards mental illness through art. It is located at 30 Royal Parade, in the Kenneth Myer Building, University of Melbourne. This exhibition is open until 29 August 2025.

Reviewer

Georgia Ruby Polichroniadis

MAT, BFA(Hons), BFA

Georgia is a recent Master of Art Therapy graduate currently working in forensic mental health. With a background in sculpture and social practice, her approach is trauma-informed, client-led, and grounded in principles of social justice. Georgia has experience facilitating art therapy in complex clinical settings, including forensic hospitals and aged care, and has co-facilitated community workshops with the Australian National Veterans Arts Museum (ANVAM). Her research and practice explore the intersections of neuroaesthetics, affect theory, and accessibility, with a focus on gender equity and community engagement. She is committed to using art as a tool for healing and systemic change.